Nineveh and Its Remains

Volume 1

By Austen Henry Layard, ESQ. D.C.L.

Part 1 - Chapter 7

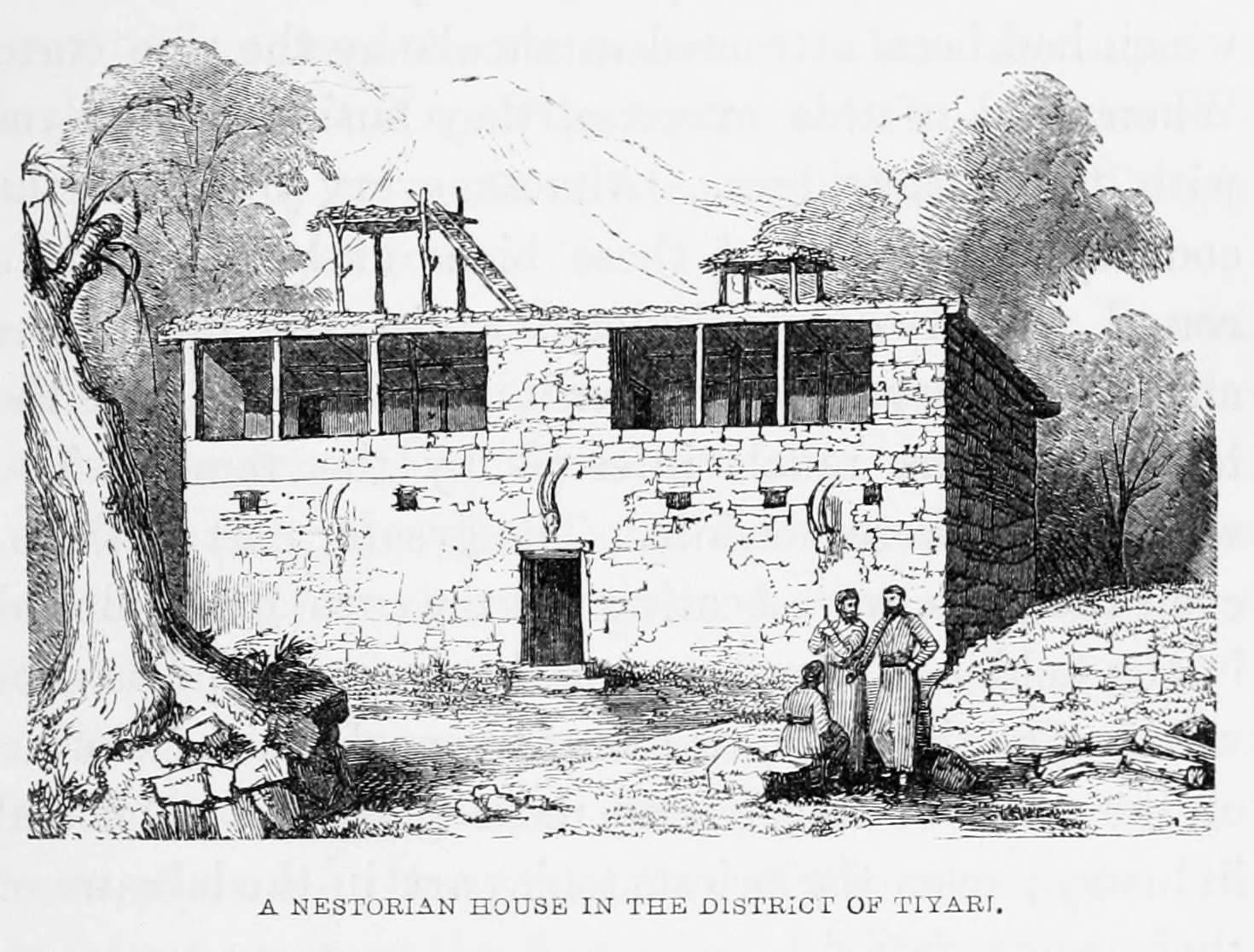

We had no sooner reached the house of Yakoub Rais, than a cry of "The Bey is come," spread rapidly through the village, and I was surrounded by a crowd of men, women, and boys. My hand was kissed by all, and I had to submit for some time to this tedious process. As for my companion, he was almost smothered in the embraces of the girls, nearly all of whom had been liberated from slavery after the great massacre, or had been supported by his brother for some months in Mosul.1 Amongst the men were many of my old workmen, who were distinguished from the rest of the inhabitants of Asheetha by their gay dresses and arms, the fruits of their industry during the winter. They were anxious to show their gratitude, and their zeal in my service. The priests came tog Kasha Ghioorghis, Kasha Hormuzd, and others. As they entered the room, the whole assembly rose; and lifting their turbans and caps reverentially from their heads, kissed the hand extended to them. In the mean while the girls had disappeared; but soon returned, each bearing a platter of fruit, which they placed before me. My workmen also brought large dishes of boiled garas swimming in butter. There were provisions enough for the whole company. The first inquiries were after Mar Shamoun, the Patriarch. I produced his letter, which the priests first kissed and placed to their foreheads. They afterwards passed it to the principal men, who went through the same ceremony. Kasha Ghioorghis then read the letter aloud, and at its close, those present uttered a pious ejaculation for the welfare of their Patriarch, and renewed their expressions of welcome to us. These preliminaries having been concluded, we had to satisfy all present as to the object, extent, and probable duration of our journey. The village was in the greatest alarm at a threatened invasion from Beder Khan Bey. The district of Tkhoma, which had escaped the former massacre, was now the object of his fanatical vengeance. He was to march through Asheetha, and orders had already been sent to the inhabitants to collect provisions for his men. As his expedition was not to be undertaken before the close of Ramazan, there was full time to see the proscribed districts before the Kurds entered them. I determined, however, to remain a day in Asheetha, to rest our mules. On the morning following;; our arrival, I went with Yakoub Rais to visit the village. The trees and luxuriant crops had concealed the desolation of the place, and had given to Asheetha, from without, a flourishing appearance. As I wandered, however, through the lanes, I found little but ruins. A few houses were rising from the charred heaps; the greater part of the sites, however, were without owners, the whole family having perished. Yakoub pointed out, as we went along, the former dwellings of wealthy inhabitants, and told me how and where they had been murdered. A solitary church had been built since the massacre, the foundations of others were seen amongst the ruins. The pathways were still blocked up by the trunks of trees cut down by the Kurds. Watercourses, once carrying fertility to many gardens were now empty and dry; and the lands which they had irri2:ated were left naked and unsown. I was surprised at the proofs of the industry and activity of the few surviving families, who had returned to the village, and had already brought a large portion of the land into cultivation. The houses of Asheetha, like those of the Tiyari districts2, are not built in a group, but are scattered over the valley. Each dwelling stands in the centre of the land belonging to its owner; consequently, the village occupies a much larger space than would otherwise be required, but has a cheerful and pleasing appearance. The houses are simple, and constructed so as to afford protection and comfort, during winter and summer. The lower part is of stone, and contains two or three rooms inhabited by the family and their cattle during the cold months. Light is admitted by the door, and by small holes in the wall. There are no windows, as in the absence of glass, a luxury as yet unknown in Kurdistan, the cold would be very great during the winter, when the inhabitants are frequently snowed up for many days together. The upper floor is constructed partly of stone, and partly of wood, the whole side facing the south being open. Enormous beams, resting on wooden pillars and on the walls, support the roof. This is the summer habitation, and here all the members of the family reside. During July and August, they usually sleep on the roof, upon which they erect stages of boughs and grass resting on high poles. By thus raising themselves as much above the ground as possible, they avoid the vermin which swarm in the rooms, and catch the night wind which carries away the gnats. Sometimes they build these stages in the branches of high trees around the houses. The winter provision of dried grass and straw for the cattle is stacked near the dwelling, or is heaped on the roof.

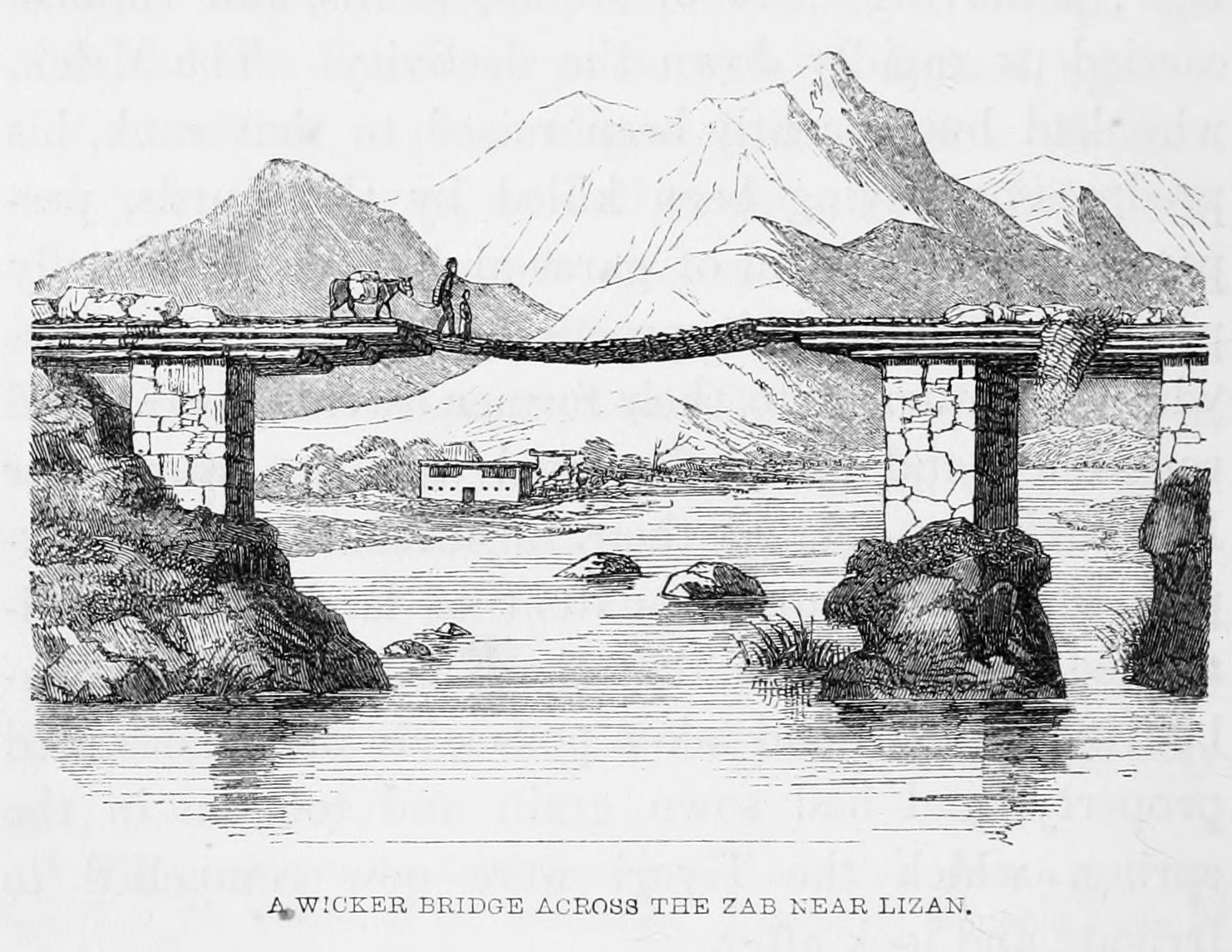

As this was the first year that the surviving inhabitants of Asheetha, about 200 families, had returned to the village and had cultivated the soil, they were almost without provisions of any kind. We were obliged to send to Zaweetha for meat and rice; and even milk was scarce, the flocks having been carried away by the Kurds. Garas was all we could find to cat. They had no corn, and very little barley. Their bread was made of this garas, and upon it alone they lived, except when on holidays they boiled the grain, and soaked it in melted butter. The men were now busy in irrigating the land; and seemed to be rewarded by the promise of ample crops of their favourite grain, and of wheat, barley, rice, and tobacco. The boys kept up a continued shrill shriek or whistle to frighten away the small birds, which had been attracted in shoals by the ripe corn. When tired of this exercise, they busied themselves with their partridges. Almost every youth in the country carries one of these birds at his back, in a round wicker cage. Indeed, whilst the mountains and the valleys swarm with wild partridges, the houses are as much infested by the tame. The women, too, were not idle. The greater part of them, even the girls, were beating out the corn, or employed in the fields. A few were at the doors of the houses working at the loom, or spinning wool for the clothes of the men. I never saw more general or cheerful industry; even the priests took part in the labours of their congregation. I walked to the ruins of the school and dwelling-house, built by the American missionaries during their short sojourn in the mountains. These buildings had been the cause of much jealousy and suspicion to the Kurds. They stand upon the summit of an isolated hill, commanding the whole valley. A position less ostentatious and proportions more modest might certainly have been chosen; and it is surprising tbcat persons, so well acquainted with the character of the tribes amongst whom they had come to reside, should have been thus indiscreet. They were, however, most zealous and worthy men; and had their plans succeeded, I have little doubt that they would have conferred signal benefits on the Nestorian Chaldeans. I never heard their names mentioned by the Tiyari, and most particularly that of Dr. Grant, without expressions of profound respect, amounting almost to veneration.3 There are circumstances connected with the massacre of the Nestorians most painful to contemplate, and which I willingly forbear to dwell upon. During the occupation of Asheetha by the Kurds, Zeinel Bey fortified himself with a few men in the house constructed by the Americans; and the position was so strong, that, holding it against all the attempts of the Tiyari to dislodge him, he kept the whole of the valley in subjection. Yakoub Rais, who was naturally of a lively and jovial disposition, could not restrain his tears as he related to me the particulars of the massacre. He had been amongst the first seized by Beder Khan Bey; and having been kept by the chief as a kind of hostage, he had been continually with him, during the attack on the Tiyari, and had-witnessed all the scenes of bloodshed which he so graphically described. The descent upon Asheetha was sudden, and unexpected. The greater part of the inhabitants fell victims to the fury of the Kurds, who endeavoured to destroy every trace of the village. We walked to the church, which had been newly constructed by the united exertions and labour of the people. The door was so low, that a person, on entering, had to perform the feat of bringing his back to the level of his knees. The entrances to Christian churches in the East, are generally so constructed that horses and beasts of burthen may not be lodged there by the Mohammedans. A few rituals, a book of prayer, and the Scriptures all in manuscript were lying upon the rude altar; but the greater part of the leaves were wanting, and those which remained were either torn into shreds, or disfigured by damp and water. The manuscripts of the churches were hid in the mountains, or buried in some secure place, at the time of the massacre; but as the priests, who had concealed them, were mostly killed, the books have not been recovered. A few English prints and handkerchiefs from Manchester were hung about the walls; a bottle and a glass, with a tin plate for the sacrament, stood upon a table; a curtain of coarse cloth hung before the inner recess, the Holy of Holies; and these were all the ornaments and furniture of the place. I visited my former workmen, the priests, and those whom I had seen at Mosul-; and as it was expected that I should partake of the hospitality of each, and eat of the dishes they had prepared for me — generally garas floating in melted rancid butter, with a layer of sour milk above — by the time I reached Yakoub's mansion, my appetite was abundantly satisfied. At the door, however, stood Sarah, and a bevy of young damsels with baskets of fruit mingled with ice, fetched from the glacier; nor would they leave me until I had tasted of every thing. We lived in a patriarchal way with the Rais. My bed was made in one corner of the room. The opposite corner was occupied by Yakoub, his wife, and unmarried daughters; a third was appropriated to his son and daughter-in-law, and all the members of his son's family; the fourth was assigned to my companion; and various individuals, whose position in our household could not be very accurately determined, took possession of the centre. We slept well nevertheless, and no one troubled himself about his neighbour. Even Ibrahim Agha, whose paradise was Chanak Kalassi, the Dardanelles, to which he always disadvantageously compared every thing, confessed that the Tiyari Mountains were not an unpleasant portion of the Sultan's dominions. Yakoub volunteered to accompany me in the rest of my journey through the mountains; and as he was generally known, was well acquainted with the by-ways and passes, and a very merry companion withal, I eagerly accepted his offer. We left part of our baggage at his house, and it was agreed that he should occasionally ride one of the mules. He was a very portly person^ gaily dressed in an embroidered jacket and striped trowsers, and carrying a variety of arms in his girdle. The country through which we passed, after leaving Asheetha, can scarcely be surpassed in the beauty and sublimity of its scenery. The patches of land on the declivities of the mountains were cultivated with extraordinary skill and care. I never saw greater proofs of industry. Our mules, however, were dragged over places almost inaccessible to men on foot; but we forgot the toils and dangers of the way in gazing upon the magnificent prospect before us. Zaweetha is in the same valley as Asheetha. The stream formed by the eternal snows above the latter village, forces its way to the Zab. On the sides of the mountains is the most populous and best cultivated district in Tiyari. The ravine below Asheetha is too narrow to admit of the road being carried along the banks of the torrent; and we were compelled to climb over an immense mass of rocks, rising to a considerable height above it. Frequently the footing was so insecure that it required the united force of several men to carry the mules along by their ears and tails. We, who were unaccustomed to mountain paths, were obliged to have recourse to the aid of our hands and knees. I had been expected at Zaweetha; and before we entered the first gardens of the village, a party of girls, bearing baskets of fruit, advanced to meet me. Their hair, neatly platted and adorned with flowers, fell down their backs. On their heads they wore coloured handkerchiefs loosely tied, or an embroidered cap. Many were pretty, and the prettiest was Aslani, a liberated slave, who had been for some time under the protection of Mrs. Rassam; she led the party, and welcomed me to Zaweetha. ]\Iy hand having been kissed by all, they simultaneously threw themselves upon my companion, and saluted him vehemently on both cheeks; such a mode of salutation, in the case of a person of my rank and distinction, not being, unfortunately, considered either respectful or decorous. The girls were followed by the Rais and the principal inhabitants, and I was led by them into the village. The Rais of Zaweetha had fortunately rendered some service to Beder Khan Bey, and on the invasion of Tiyari his village was spared. It had not even been deserted by its inhabitants, nor had its trees and gardens been injured. It was consequently, at the time of my visit, one of the most flourishing villages in the mountains. The houses, neat and clean, were still overshadowed by the wide-spreading walnut-tree; every foot of ground which could receive seed, or nourish a plant, was cultivated. Soil had been brought from elsewhere, and built up in terraces on the precipitous sides of the mountains. A small pathway amongst the gardens led us to the house of the Rais. We were received by Kasha Kana of Lizan, and Kasha Yusuf of Siatha; the first, one of the very few learned priests left among the Nestorian Chaldeans. Our welcome was as unaffected and sincere as it had been at Asheetha. Preparations had been made for our reception, and the women of the family of the chief were congregated around huge cauldrons at the door of the house, cooking an entire sheep, rice, and garas. The liver, heart, and other portions of the entrails, were immediately cut into pieces, roasted on ramrods, and brought on these skewers into the room. The fruit too, melons, pomegranates, and grapes, all of excellent quality, spread on the floor before us, served to allay our appetites until the breakfast was ready. Mar Shamoun's letter was read with the usual solemnities by Kasha Kana, and we had to satisfy the numerous inquiries of the company. Their Patriarch was regarded as a prisoner in Mosul, and his return to the mountains was looked forward to with deep anxiety. Everywhere, except in Zaweetha, the churches had been destroyed to their foundations, and the priests put to death. Some of the holy edifices had been rudely rebuilt; but the people were unwilling to use them until they had been consecrated by the Patriarch. There were not priests enough indeed to officiate, nor could others be ordained until Mar Shamoun himself performed the ceremony. These wants had been the cause of great irregularities and confusion in Tiyari; and the Nestorian Chaldeans, who are naturally a religious people, and greatly attached to their churches and ministers, were more alive to them than to any of their misfortunes. Kasha Kana was making his weekly rounds to the villages which had lost their priests. He carried under his arm a bag full of manuscripts, consisting chiefly of rituals and copies of the Scriptures; but he had also one or two volumes on profane subjects which he prized highly; amongst them was a Grammar by Rabba lohannan bar Zoabee, to which he was chiefly indebted for his learning. He read to us — holding as usual the book upside down — a part of the introduction treating of the philosophy and nature of languages, and illustrated the text by various attempts at the delineation of most marvellous alphabets. A taste for the fine arts seemed to prevail generally in the village, and the walls of the Rais's house were covered with sketches of wild goats and snakes in every variety of posture. The young men were eloquent on the subject of the chase, and related their exploits with the wild animals of the mountains. A cousin of the chief, a handsome youth very gaily dressed, had shot a bear a few days before, after a hazardous encounter, and he brought me the skin, which measured seven feet in length. The two great subjects of complaint I found to be the Kurds and the bears, both equally mischievous; the latter carrying off the fruit both when on the trees and when laid out to dry; and the former, the provisions stored for the winter. In some villages in Berwari the inhabitants pretended to be in so much dread of the bears, that they would not venture out alone after dark. The Rais, finding that I would not accept his hospitality for the night, accompanied us, followed by all the inhabitants, to the outskirts of the village. His frank and manly bearing, and simple kindness, had made a most favourable impression upon me, and I left him with regret. Kasha Kana, too, fully merited the praise which he received from all who knew him. His appearance was mild and venerable; his beard, white as snow, fell low upon his breast; but his garments were in a very advanced stage of rags. I gave him a few handkerchiefs, some of which were at once gratefully applied to the bettering of his raiment; the remainder being reserved for the embellishment of his parish church. The Kasha is looked up to as the physician, philosopher, and sage of Tiyari, and is treated with great veneration by the people. As we walked through the village, the women left their thresholds and the boys their sports to kiss his hand — a mark of respect, however, which is invariably shown to the priesthood. We had been joined by Mirza, a confidential servant of Mar Shamoun, and our party was further increased by several men returning to villages on our road. Yakoub Rais kept every one in good humour by his anecdotes, and the absurdity of his gesticulations, lonunco too, dragging his mare over the projecting rocks, down which he generally contrived to tumble, added to the general mirth, and we went laughing through the valley. From Zaweetha to the Zab, there is almost an unbroken line of cultivation on both sides of the valley. The two villages of Miniyanish and Murghi are almost buried in groves of walnut-trees, and their peaceful and flourishing appearance deceived me until I wandered amongst the dwellings, and found the same scenes of misery and desolation that I had witnessed at Asheetha. But nature was so beautiful that we almost forgot the havoc of man, and envied the repose of these secluded habitations. In Miniyanish, out of seventy houses, only twelve had risen from their ruins; the families to which the rest belonged having been totally destroyed. Yakoub pointed out a spot where above three hundred persons had been murdered in cold blood, and all our party had some tale of horror to relate. Murghi was not less desolate than Miniyanish, and eight houses alone had been resought by their owners. We found an old priest, blind and grey, bowed down by age and grief, the solitary survivor of six or eight of his order. He was seated under the shade of a walnut-tree, near a small stream. Some children of the village were feeding him with grapes, and on our approach his daughter ran into the half-ruined cottage, and brought out a basket of fruit and a loaf of garas bread. I endeavoured to glean some information from the old man as to the state of his flock; but his mind wandered to the cruelties of the Kurds, or dwelt upon the misfortunes of his Patriarch, over whose fate he shed many tears. None of our party being able to console the Kasha, I gave some handkerchiefs to his daughter, and we resumed our journey. Our road lay through the gardens of the villages, or through the forest of gall-bearing oaks which clothe the mountains above the line of cultivation. But it was everywhere equally difficult and precipitous, and we tore our way through the matted boughs of overhanging, trees, or the thick foliage of creepers which hung from every branch. Innumerable rills, led from the mountain springs into the terraced fields, crossed our path and rendered our progress still more tedious. We reached Lizan, however, early in the afternoon, descending to the village through scenery of extraordinary beauty and grandeur. Lizan stands on the river Zab, which is crossed by a rude bridge. I need not weary or distress the reader with a description of desolation and misery, hardly concealed by the most luxuriant vegetation. We rode to the graveyard of a roofless church slowly rising from its ruins — the first edifice in the village to be rebuilt. We spread our carpets amongst the tombs; for as yet there were no inhabitable houses. The Melek, with the few who had survived the massacre, was living during the day under the trees, and sleeping at night on stages of grass and boughs, raised on high poles, fixed in the very bed of the Zab. By this latter contrivance they succeeded in catching any breeze that might be carried down the narrow ravine of the river, and in freeing themselves from the gnats and sandflies abounding in the valley. It was near Lizan that occurred one of the most terrible incidents of the massacre; and an active mountaineer offering to lead me to the spot, I followed him up the mountain. Emerging from the gardens we found ourselves at the foot of an almost perpendicular detritus of loose stones, terminated, about one thousand feet above us, by a wall of lofty rocks. Up this ascent we toiled for above an hour, sometimes clinging to small shrubs, whose roots scarcely reached the scanty soil below; at others crawling on our hands and knees; crossing the gullies to secure a footing, or carried down by the stones which we put in motion as we advanced. We soon saw evidences of the slaughter. At first a solitary skull rolling down with the rubbish; then heaps of blanched bones; further up fragments of rotting garments. As we advanced, these remains became more frequent — skeletons, almost entire, still hung to the dwarf shrubs. I was soon compelled to renounce an attempt to count them. As we approached the wall of rock, the declivity became covered with bones, mingled with the long platted tresses of the women, shreds of discoloured linen, and well-worn shoes. There were skulls of all ages, from the child unborn to the toothless old man. We could not avoid treading on the bones as we advanced, and rolling them with the loose stones into the valley below. " This is nothing," exclaimed my guide, who observed me gazing with wonder on these miserable heaps; " they are but the remains of those who were thrown from above, or sought to escape the sword by jumping from the rock. Follow me!" He sprang upon a ledge running along the precipice that rose before us, and clambered along the face of the mountain overhanging the Zab, now scarcely visible at our feet. I followed him as well as I was able to some distance; but when the ledge became scarcely broader than my hand, and frequently disappeared for three or four feet altogether, I could no longer advance. The Tiyari, who had easily surmounted these difficulties, returned to assist me, but in vain. I was still suffering severely from the kick received in my leg four days before; and was compelled to return, after catching a glimpse of an open recess or platform covered with human remains. When the fugitives who had escaped from Asheetha, spread the news of the massacre through the valley of Lizan, the inhabitants of the villages around collected such part of their property as they could carry, and took refuge on the platform I have just described and on the rock above; hoping thus to escape the notice of the Kurds, or to be able to defend, against any numbers, a place almost inaccessible. Women and young children, as well as men, concealed themselves in a spot which the mountain goat could scarcely reach.4 Beder Khan Bey was not long in discovering their retreat; but being unable to force it, he surrounded the place with his men, and waited until they should be compelled to yield. The weather was hot and sultry; the Christians had brought but small supplies of water and provisions; after three days the first began to fail them, and they offered to capitulate. The terms proposed by Beder Khan Bey, and ratified by an oath on the Koran, were the surrender of their arms and property. The Kurds were then admitted to the platform. After they had taken the arms from their prisoners, they commenced an indiscriminate slaughter; until weary of using their weapons, they hurled the few survivors from the rocks into the Zab below. Out of nearly one thousand souls, who are said to have congregated here, only one escaped. We had little difficulty in descending to the village; a moving mass of stones, skulls, and rubbish carried us rapidly down the declivity. The Melek, who had but recently been raised to that rank, his predecessor having been killed by the Kurds, prepared a simple meal of garas and butter — the only provisions that could be procured. The few stragglers who had returned to their former dwellings collected round us, and made the usual inquiries after their Patriarch, or related their misfortunes. As I expressed surprise at the extent of land already cultivated, they told me that the Kurds of some neighbouring villages had taken possession of the deserted property, and had sown grain and tobacco in the spring, which the Tiyari were now compelled to irrigate and look after. The sun had scarcely set, when I-was driven by swarms of insects to one of the platforms in the river. A slight breeze came from the ravine, and I was able to sleep undisturbed. The bridge across the Zab at Lizan is of basket-work. Stakes are firmly fastened together with twigs, forming a long hurdle, reaching from one side of the river to the other. The two ends are laid upon beams, resting upon piers on the opposite banks. Both the beams and the basket-work are kept in their places by heavy stones heaped upon them. Animals, as well as men, are able to cross over this frail structure, which swings to and fro, and seems ready to give way at every step. These bridges are of frequent occurrence in the Tiyari mountains.