Nineveh and Its Remains

Volume 1

By Austen Henry Layard, ESQ. D.C.L.

Part 1 - Chapter 5

On my return to Mosul I hastened back to Nimroud, During my absence little progress had been made, as only two men had been employed in removing the rubbish from the upper part of the chamber to which the great human-headed lions formed an entrance. The lions to the east of them (entrance d) had, however, been completely uncovered; that to the right (No. 2.) had fallen from its place, and was sustained by the opposite sculpture. Between them was a large pavement slab covered with cuneiform characters. In clearing the earth from this entrance, and from behind the fallen lion, many ornaments in copper, two small ducks in baked clay, and tablets of alabaster inscribed on both sides were discovered.1 Amongst the copper mouldings were the head of a ram or a bull2, several hands (the fingers closed and slightly bent), and a few flowers. The hands may have served as a casing to similar objects in baked clay, frequently found amongst the ruins, and having an inscription, containing the names, titles, and genealogy of the King, graved upon the fingers. The heads of the ducks, for they resemble that bird more than any other, are turned and rest upon the back, which is covered with cuneiform characters. Objects somewhat similar have been found in Egypt. It is difficult to determine the original site of the small tablets. They appeared to me to have been built up ill the walls above the slabs, or to have been placed behind the slabs themselves, and this conjecture was confirmed by subsequent discoveries. The inscription upon them resembled that on all the slabs in the N. W. palace. It was remarkable that whilst such parts of the chamber B as had been uncovered were paved with kiln-burnt bricks, and the entrance d with a large slab of alabaster, between the two great lions there was only a flooring of common sun-dried brick. In the middle of the entrance, near the forepart of the lions, were a few square stones carefully placed. I expected to find under them small figures in clay, similar to those discovered by M. Botta in the doorways at Khorsabad, but nothing of the kind existed. As several of the principal Christian families of Mosul were anxious to see the sculptures, whose fame had been spread over the town and provinces, I was desirous of gratifying their curiosity before the heat of summer had rendered the plain of Nimroud almost uninhabitable. An opportunity at the same time presented itself of securing the good- will of the Arab tribes encamping near the ruins, by preparing an entertainment which might gratify all parties. The Christian ladies, who had never before been out of sight of the walls of their houses, were eager to see the wonders of Nimroud, and availed themselves joyfully of the permission, with difficulty extracted from their husbands, to leave their homes. The French consul and his wife, and Mr. and Mrs. Rassam joined the party. On the day after their arrival I issued a general invitation to all the Arabs of the district, men and women. White pavilions, borrowed from the Pasha, had been pitched near the river, on a broad lawn still carpeted with flowers. These were for the ladies, and for the reception of the Sheikhs. Black tents were provided for some of the guests, for the attendants and for the kitchen. A few Arabs encamped around us to watch the horses, which were picketted on all sides. An open space was left in the centre of the group of tents for dancing, and for various exhibitions provided for the entertainment of the company. Early in the morning came Abd-ur-rahman, mounted on a tall white mare. He had adorned himself with all the finery he possessed. Over his keffiah, or head-kerchief, was folded a white turban, edged with long fringes which fell over his shoulders, and almost concealed his handsome features. He wore a long robe of red silk and bright yellow boots, an article of dress much prized by Arabs. He was surrounded by horsemen carrying spears tipped with tufts of ostrich feathers. As the Sheikh of the Abou- Salman approached the tents I rode out to meet him. A band of Kurdish musicians, hired for the occasion, advanced at the same time to do honour to the Arab chief. As they drew near to the encampment, the horsemen, led by Schloss, the nephew of Abd-ur-rahman, urged their mares to the utmost of their speed, and engaging in mimic war, filled the air with their wild war-cry. Their shoutings were, however, almost drowned by the Kurds, who belaboured their drums, and blew into their pipes with redoubled energy. Sheikh Abd-ur-rahman, having dismounted, seated himself with becoming gravity on the sofa prepared for guests of his rank; whilst his Arabs picketted their mares, fastening the halters to their spears driven into the ground. The Abou-Salman were followed by the Shemutti and Jehesh, who came with their women and children on foot, except the Sheikhs, who rode on horseback. They also chanted their peculiar war-cry as they advanced. When they reached the tents, the chiefs placed themselves on the divan, whilst the others seated themselves in a circle on the greensward. The wife and daughter of Abd-ur-rahman, mounted on mares, and surrounded by their slaves and handmaidens, next appeared. They dismounted at the entrance of the ladies' tents, where an abundant repast of sweetmeats, halwa, parched peas, and lettuces had been prepared for them. Fourteen sheep had been roasted and boiled to feast the crowd that had assembled. They were placed on large wooden platters, which, after the men had satisfied themselves, were passed on to the women. The dinner having been devoured to the last franrment, dancing succeeded. Some scruples had to be overcome before the women would join, as there were other tribes, besides their own, present; and when at length, by the exertions of Mr. Hormuzd Rassam, this difficulty was overcome, they made up different sets. Those who did not take an active share in the amusements seated themselves on the grass, and formed a large circle round the dancers. The Sheikhs remained on the sofas and divans. The dance of the Arabs, the Debkè, as it is called, resembles in some respects that of the Albanians, and those who perform in it are scarcely less vehement in their gestures, or less extravagant in their excitement, than those wild mountaineers. They form a circle, holding one another by the hand, and, moving slowly round at first, go through a shuffling step with their feet, twisting their bodies into various attitudes. As the music quickens, their movements are more active; they stamp with their feet, yell their war-cry, and jump as they hurry round the musicians. The motions of the women are not without grace; but as they insist on wrapping themselves in their coarse cloaks before they join in the dance, their forms, which the simple Arab shirt so well displays, are entirely concealed. When those who formed the Debkè were completely exhausted by their exertions, they joined the lookers-on, and seated themselves on the ground. Two warriors of different tribes, furnished with shields and drawn scimitars, then entered the circle, and went through the sword-dance. As the music quickened, the excitement of the performers increased. The bystanders at length were obliged to interfere, and to deprive the combatants of their weapons, which were replaced by stout staves. With these they belaboured one another unmercifully to the great enjoyment of the crowd. On every successful hit, the tribe, to which the one who dealt it belonged, set up their war-cry and shouts of applause, whilst the women deafened us with the shrill "tahlehl," a noise made by a combined motion of the tongue, throat, and hand vibrated rapidly over the mouth. When an Arab or a Kurd hears this tahlehl he almost loses his senses through excitement, and is ready to commit any desperate act. A party of Kurdish jesters from the mountains entertained the Arabs with performances and imitations, more amusing than refined. They were received with shouts of laughter. The dances were kept up by the light of the moon, the greater part of the night. On the following morning Abd-ur-rahman invited us to his tents, and we were entertained with renewed Debkès and sword-dances. The women, undisturbed by the presence of another tribe, entered more fully into the amusement, and danced with greater animation. The Sheikh insisted upon my joining with him in leading off a dance, in which we were joined by some live hundred warriors, and Arab women. His admiration of the beauty of the French lady who accompanied us exceeded all bounds, and when he had ceased dancing, he sat gazing upon her from a corner of the tent — "Wallah," he whispered to me, " she is the sister of the Sun! what would you have more beautiful than that? Had I a thousand purses, I would give them all for such a wife. See! — her eyes are like the eyes of my mare, her hair is as bitumen, and her complexion resembles the finest Busrah dates. Any one would die for a Houri like that." The Sheikh w^as almost justified in his admiration. The festivities lasted three days, and made the impression I had anticipated. They earned me a great reputation and no small respect, the Arabs long afterwards talking of their reception and entertainment. When there was occasion for their services, I found the value of the feeling towards me, which a little show of kindness to these ill-used people had served to produce. Hafiz Pasha, who had been appointed to succeed the last governor, having received a more lucrative post, the province was sold to Tahyar Pasha. He made his public entry into Mosul early in May, and I rode out to meet him. He was followed by a large body of troops, and by the Cadi, Mufti, Ulema, and principal inhabitants of the town, who had been waiting for him at some distance from the gates to show their respect. The Mosuleeans had not been deceived by the good report of his benevolence and justice which had preceded him. He was a venerable old man, bland and polished in his manners, courteous to Europeans, and well informed on subjects connected with the literature and history of his country. He was a perfect specimen of the Turkish gentleman of the old school, of whom few are now left in Turkey. I had been furnished with serviceable letters of introduction to him; he received me with every mark of attention, and at once permitted me to continue the excavations. As a matter of form, he named a Cawass, to superintend the work on his part. I willingly concurred in this arrangement, as it saved me from any further inconvenience on the score of treasure; for which, it was still believed, I was successfully searching. This officer's name was Ibrahim Agha. He had been many years with Tahyar, and was a kind of favourite. He served me during my residence in Assyria, and on my subsequent journey to Constantinople, with great fidelity; and, as is very rarely the case with his fraternity, with great honesty. The support of Tahyar Pasha relieved me from some of my difficulties; for there was no longer cause to fear any interruption on the part of the authorities. But my means were very limited, and my own resources did not enable me to carry on the excavations as I wished. I returned, however, to Nimroud, and formed a small but effective body of workmen, choosing those who had already proved themselves equal to the work. The heats of summer had now commenced, and it was no longer possible to live under a white tent. The huts were equally uninhabitable, and still swarmed with vermin. In this dilemma I ordered a recess to be cut into the bank of the river, where it rose perpendicularly from the water's edge. By skreening the front with reeds and boughs of trees, and covering the whole with similar materials, a small room was formed. I was much troubled, however, with scorpions and other reptiles, which issued from the earth forming the walls of my apartment; and later in the summer by the gnats and sandflies, which hovered on a calm night over the river. Similar rooms were made for my servants. They were the safest that could be invented, should the Arabs take to stealing after dark. My horses were picketted on the edge of the bank above, and the tents of my workmen were pitched in a semi-circle behind them. The change to summer had been as rapid as that which ushered in the spring. The verdure of the plain had perished almost in a day. Hot winds, coming from the desert, had burnt up and carried away the shrubs; flights of locusts, darkening the air, had destroyed the few patches of cultivation, and had completed the havoc commenced by the heat of the sun. The Abou-Salman Arabs, having struck their black tents, were now living in ozailis, or sheds, constructed of reeds and grass along the banks of the river. The Shemutti and Jehesh had returned to their villages, and the plain presented the same naked and desolate aspect that it wore in the month of November. The heat, however, was now almost intolerable. Violent whirlwinds occasionally swept over the face of the country. They could be seen as they advanced from the desert, carrying along with them clouds of sand and dust. Almost utter darkness prevailed during their passage, which lasted generally about an hour, and nothing could resist their fury. On returning home one afternoon after a tempest of this kind, I found no traces of my dwellings; they had been completely carried away. Ponderous wooden frameworks had been borne over the bank, and hurled some hundred yards distant; the tents had disappeared, and ray furniture was scattered over the plain. When on the mound, my only secure place of refuge was beneath the fallen lion, where I could defy the fury of the whirlwind; the Arabs ceased from their work and crouched in the trenches, almost suffocated and blinded by the dense cloud of fine dust and sand which nothing of could exclude.3 Although the number of my workmen was small, the excavations were carried on as actively as possible. The two human-headed lions, forming the entrance d4, led into another chamber, or to sculptured walls, which, as it will hereafter be explained, may have formed an outward facing to the building. The slabs to the right and left, on issuing from this portal, had fallen from their original position, and all of them, except one, were broken. I had some difficulty in raising the pieces from the ground. As the face of the slabs was downwards, the sculpture had been well preserved.

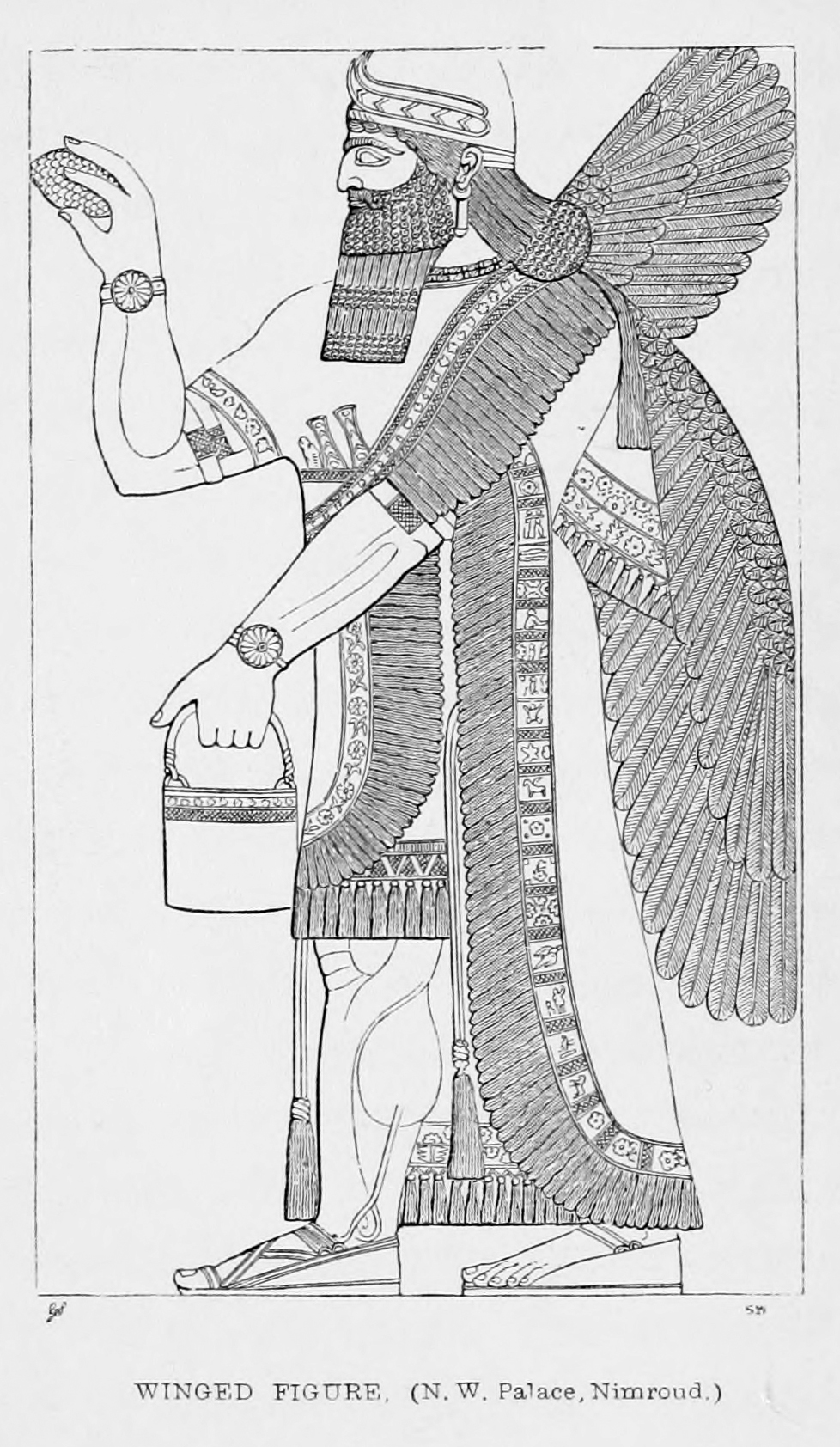

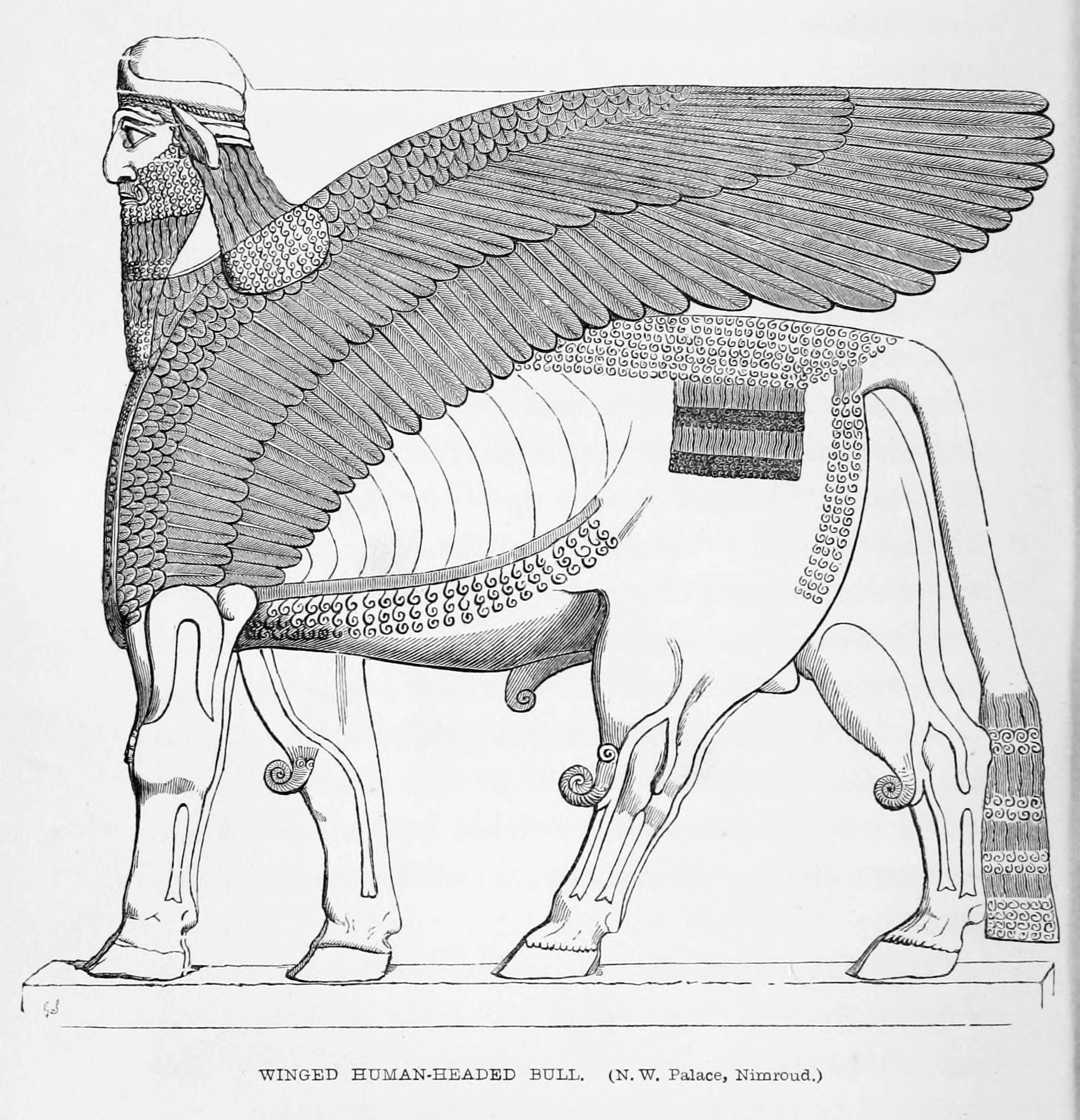

On the slabs Nos. 2. and 3. was represented the King, holding a bow in one hand and two arrows in the other. He was followed by his attendant eunuch, who carried a mace, a second bow and a quiver for his use. Facing him was his vizir, his hands crossed before him, also followed by an eunuch. These figures were about eight feet high; the relief very low, and the ornaments rich and elaborately carved. The bracelets, armlets, and weapons, were all adorned with the heads of bulls and rams; colour still remained on the hair, beard, and sandals. No. 1. forming a corner wall, was a slab of enormous dimensions; it had been broken in two: the upper part was on the floor, the lower was still standing in its place. It was only after many ineffectual attempts that I succeeded in raising the fallen part sufficiently to ascertain the nature of the sculpture. It was a winged figure, with a three horned cap, carrying the fir cone and square utensil; in other respects, similar to those already described, except that it had two wings rising from both sides of the back and enclosing the person. Its dimensions were gigantic, the height being about sixteen feet and a half, but the relief was low. The first slab on the other side of the entrance contained a vizir and his attendant, similar to No. 3. The succeeding slabs were occupied by figures, differing altogether in costume from those previously discovered, and apparently representing people of another race; some carrying presents or offerings, consisting of armlets, bracelets, and earrings on trays; others elevating their clenched hands, either in token of submission, or in the attitude still peculiar to Easterns when they dance. One figure was accompanied by two monkeys, held by ropes; the one raising itself on its hind legs in front, the other sitting on the shoulders of the man, and supporting itself by placing its fore paws on his head.5 The dresses of all these figures are singular. They have high boots turned up at the toes, somewhat resembling those still in use in Turkey and Persia. Their caps, although conical, appear to have been made up of bands, or folds of felt or linen. Their tunics vary in shape, and in the fringes, from those of the high-capped warriors and attendants represented in other bas-reliefs. The figure with the monkeys wears a tunic descending to the calf of the leg. His hair is simply fastened by a fillet. There were traces of black colour all over the face, and it is not improbable that it was painted to represent a negro: it is, however, possible that the paint of the hair has been washed down by water over other parts of the sculpture. These peculiarities of dress suggest that the persons represented were captives from some distant country, bringing tribute to the conquerors. In chamber B the wall was continued to the south, or to the left facing the great lion6, by an eagle-headed figure resembling that already described; adjoining it was a corner stone, occupied by the sacred tree; beyond, the wall ceased altogether. On digging downwards, it was found that the slabs had fallen in; and although they were broken, the sculptures, representing battles, sieges, and other historical subjects, were, as far as it could be ascertained by the examination of one or two, in admirable preservation. The sun-dried brick wall, against which they were placed, was still distinctly visible to the height of twelve or fourteen feet; and I could trace, by the accumulation of ashes, the places where beams had been inserted to support the roof, or for other purposes. This wall served as my guide in digging onwards, as, to the distance of 100 feet, the slabs had all fallen in. I was unwilling to raise them at present, as I had neither the means of packing nor moving them. The first sculpture, still standing in its original position, which was uncovered after following this wall, was a winged human-headed bull of yellow limestone. On the previous day the detached head, now in the British Museum, had been found. The bull, to which it belonged, had fallen against the opposite sculpture, and had been broken by the fall into several pieces. I lifted the body with difficulty; and, to my surprise, discovered under it sixteen copper lions, admirably designed, and forming a regular series, diminishing in size from the largest, which was above one foot in length, to the smallest, which scarcely exceeded an inch. To their backs was affixed a ring, giving them the appearance of weights. Here I also discovered a broken earthen vase, on which were represented two Priapean human figures, with the wings and claws of a bird, the breast of a woman, and the tail of a scorpion, or some similar reptile. I carefully collected and packed the fragments. Beyond the winged bull the slabs were still entire, and occupied their original positions. On the first was sculptured a winged human figure, carrying a branch with five flowers in the raised right hand, and the usual square vessel in the left. Around his temples was a fillet adorned with three rosettes. On each of the four adjoining slabs were two bas-reliefs, separated by a band of inscriptions. The upper, on the first slab, represented a castle built by the side of a river, or on an island. One tower is defended by an armed man, two others are occupied by females. Three warriors, probably escaping from the enemy, are swimming across the stream; two of them on inflated skins, in the mode practised to this day by the Arabs inhabiting the banks of the rivers of Assyria and Mesopotamia; except that, in the bas-relief, the swimmers are pictured as retaining the aperture, through which the air is forced, in their mouths. The third, pierced by arrows discharged from the bows of two high-capped warriors kneeling on the bank, is struggling, without the support of a skin, against the current. Three rudely designed trees complete the back-ground. In the upper compartment of the next slab was the siege of the city, with the battering-ram and movable tower, now in the British Museum. The lower part of the two slabs was occupied by one subject, a king receiving prisoners brought before him by his vizir. The sculpture, representing the king followed by his attendants and chariot, is already in the national collection. The prisoners were on the adjoining slab. Above their heads are vases and various objects, amongst which appear to be shawls and elephants' tusks, probably representing the spoil carried away from the conquered nation. Upon the third slab were, in the upper compartment, the king hunting, and in the lower, the king standing over the lion, both deposited in the British Museum; and on the fourth the bull hunt, now also in England, and the king standing over the prostrate bull. The most remarkable of the sculptures hitherto discovered was the lion hunt; which, from the knowledge of art displayed in the treatment and composition, the correct and effective delineation of the men and animals, the spirit of the grouping, and its extraordinary preservation, is probably the finest specimen of Assyrian art in existence. On the flooring, below the sculptures, were discovered considerable remains of painted plaster still adhering to the sun-dried bricks, which had fallen in masses from the upper part of the wall. The colours, particularly the blues and reds, were as brilliant and vivid when the earth was removed from them, as they could have been when first used. On exposure to the air they faded rapidly. The designs were elegant and elaborate. It was found almost impossible to preserve any portion of these ornaments, the earth crumbling to pieces when an attempt was made to raise it. About this time I received the vizirial letter procured by Sir Stratford Canning, authorising the continuation of the excavations and the removal of such objects as might be discovered. I was sleeping in the tent of Sheikh Abd-ur-rahman, who had invited me to hunt gazelles with him before dawn on the following morning, when an Arab awoke me. He was the bearer of letters from Mosul, and I read by the light of a small camel-dung fire, the document which secured to the British nation the records of Nineveh, and a collection of the earliest monuments of Assyrian art. The vizirial order was as comprehensive as could be desired; and having been granted on the departure of the British ambassador, was the highest testimony the Turkish government could give of their respect for the character of Sir Stratford Canning, and of their appreciation of the eminent services he had rendered them. One of the difficulties, and not one of the least which had to be encountered, was now completely removed. Still, however, pecuniary resources were wanting, and in the absence of the necessary means, extensive excavations could not be carried on. I hastened, nevertheless, to communicate the letter of the Grand Vizir to the Pasha, and to make arrangements for pursuing the researches as effectually as possible.

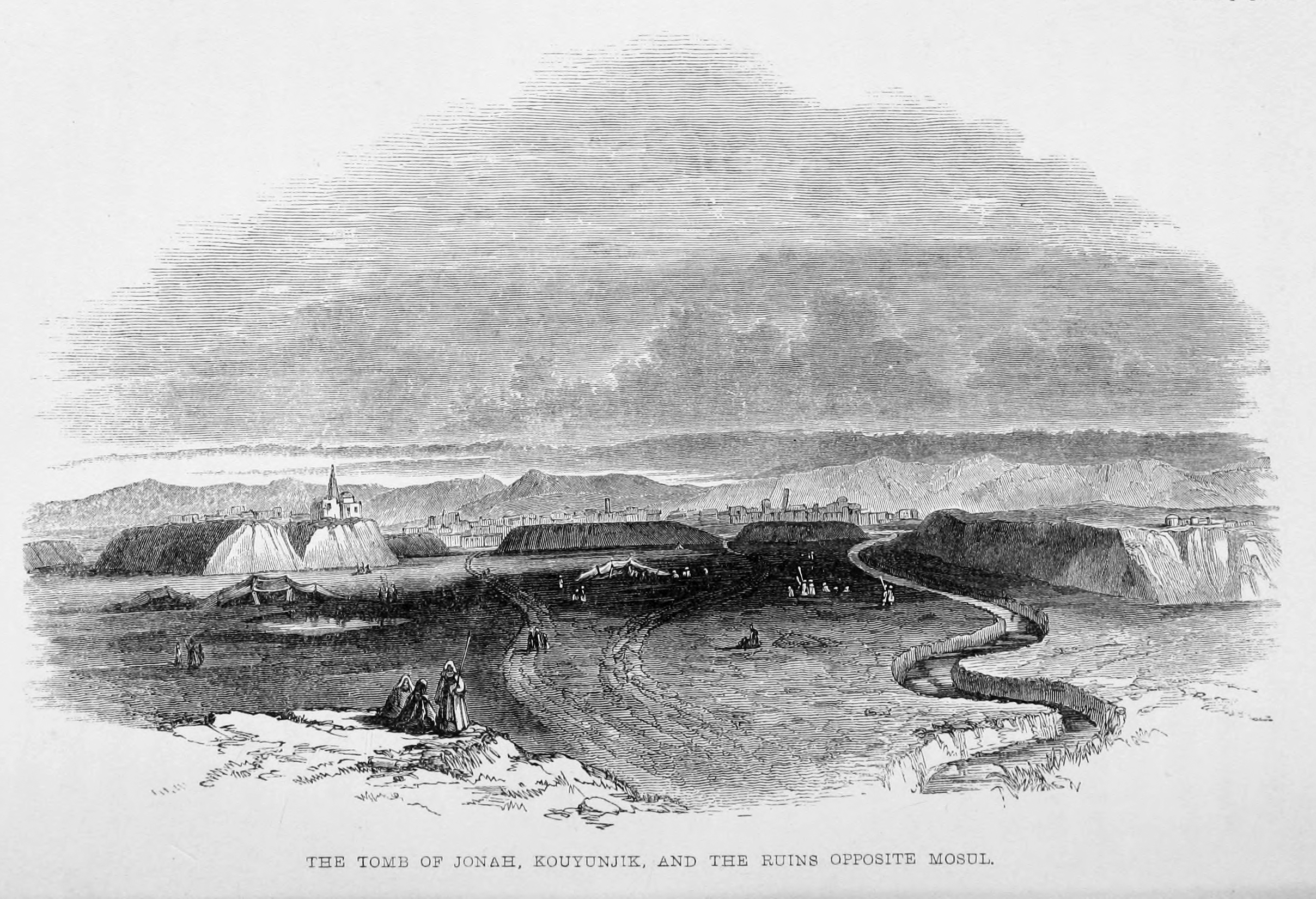

Not having yet examined the great mound of Kouyunjik, which, as it has already been observed, has generally been believed by travellers to mark the true site of Nineveh, I determined to open trenches in it. I had not previously done so, as the vicinity of the ruins to Mosul would have enabled the inhabitants of the town to watch my movements, and to cause me continual interruptions before the sanction of the authorities could be obtained to my proceedings. A small party of workmen having been organised, excavations were commenced on the southern face, where the mound was highest; as sculptures, if any still existed, would probably be found in the best state of preservation under the largest accumulation of rubbish. The only opposition I received was from the French Consul, who claimed the ruins as French property. The claim not being recognised, he also dug into the mound, but in another direction. We both continued our researches for about a month without much success. A few fragments of sculpture and inscriptions were discovered, which enabled me to assert with some confidence that the remains were those of a building contemporary, or nearly so, with Khorsabacl, and consequently of a more recent epoch than the most ancient palace of Kimroud. All the bricks dug out bore the name of the same king, but I could not find any traces of his genealogy. On my return to Nimroud, about thirty men, chiefly Arabs, were employed to carry on the excavations. Being anxious to learn a§ soon as possible the extent of the building, and the nature of the sculptures it contained, I merely dug down to the top of the slabs and ascertained the character of the sculpture upon them, reserving a completer examination for a more favourable opportunity. I was thus able to form an opinion as to the number of bas-reliefs that could be removed, and to preserve those partially uncovered from injury, by heaping the rubbish again over them. United to the last of the four slabs with small bas-reliefs, beyond the bulls of yellow limestone, was an ornamented corner-stone marking the end of hall B., the length of which could now be ascertained. Its dimensions were peculiar — 154 feet in length by 33 in breadth — resembling in its narrowness the chambers of Khorsabad, though exceeding them all in its proportions. Adjoining the corner-stone was a winged figure; beyond it a slab 14 feet in length cut into a recess, in which are four figures. Two kings stand facing one another, but separated by the symbolic tree, above which is the divinity, with the wings and tail of a bird, enclosed in a circle, and holding a ring in one hand, resembling the image so frequently occurring on the early sculptures of Persia, and at one time conjectured to be the Zoroastrian "ferouher," or spirit of the person beneath. the fact of the identity of this figure with the Persian symbol is remarkable, and gives rise to new speculations and conjectures, which will be alluded to hereafter. Each king holds a mace or instrument formed by a handle with a ball or circle at the end7, and is followed by a winged figure carrying the fir-cone and basket. This bas-relief is well designed and delicately carved, and the ornaments on the dresses and arms of the figures are elegant and elaborate.8 This large slab was followed by a winged figure similar to that preceding it, and the end of the hall was formed by a second ornamented corner-stone. The half of both the winged figures adjoining the centre slab, as well as the lower part of that slab, which advanced beyond the sculpture, had been purposely destroyed, and the stone still bore the marks of the chisel. Subsequent excavations disclosed in front of the large bas-relief a slab of alabaster, 10 feet by 8, and about 2 feet thick, cut at the western end into steps or gradines. It appeared to be a raised place for a throne, or to be an altar on which sacrifices were made: the latter conjecture was strengthened by a conduit for water or some other fluid, also of alabaster, being carried round the stone, which was covered on both sides with inscriptions. On raising it, a process of considerable difficulty from its weight and size, I found underneath a few pieces of gold-leaf and fragments of bones. In the northern corner of the same part of the chamber, and near this slab, were two square stones slightly hollowed in the centre. The first slab forming the northern wall after the corner-stone, was occupied by a human figure, with four wings; his right hand was raised, and in his left was a mace. Beyond were two lions9 to correspond with those forming the entrance d, from which they differed somewhat in form, the hands being crossed in front, and no animal being carried on the arm. They led to an outer wall or vestibule similar to that marked E, in the 3rd plan. The bas-reliefs represented figures bearing ornaments: there was another gigantic figure like that already described, which was also broken into two pieces. As the edge of a deep ravine had now been reached by the trenches, the workmen were directed to return to the yellow bulls, which were found to form the entrance into a new chamber, marked F in the 3rd plan. I only partly uncovered the slabs as far as the entrance a, and three to the west of it. On No. 4. was a king attended by eagle-headed figures. Around his neck were suspended the symbolic or astronomical signs, which are frequently found in Assyrian monuments; sometimes detached and placed close to the principal personage, enclosed in a square or scattered over the slab10; at others forming a part of his attire. They are generally five in number, and include the sun, a star, a half-moon, a three-pronged or two-pronged instrument, and a horned cap similar to that worn by the human-headed bulls, and the winged figures in chamber B. All the other slabs in this chamber were occupied by eagle-headed figures in pairs, facing one another and separated by the usual symbolic tree. The entrance a was formed by four slabs, on two of which (Nos. 1. and 2.) were figures without wings, with the right hand raised, and carrying in the left a mystic flower; and on the others simply the often-repeated inscription. This entrance led me into a new chamber, remarkable for the elaborate and careful finish of its sculptures, and the size of its slabs. I uncovered the northern wall, and the eastern as far as the entrance e.11 Each slab, except the corner-stones, was occupied by two figures about eight feet in height. Nos. 2, 3, and 4. formed one group. On the centre slab No. 3. is the king seated on a stool or throne of most elegant design and careful workmanship. His feet are placed upon a footstool supported by lion's paws. In his elevated right hand he holds a cup; his left rests upon his knee. His attire and head-dress resemble those of the kings in other bas-reliefs, but the robes are covered with the most elaborate embroidery. Upon his breast, and forming a border to which fringes are attached, are graved a variety of religious emblems, and figures found upon cylinders and seals of Assyria and Babylon. Amongst them are men struggling with animals, winged horses, griffins, the sacred tree, and the king himself engaged in the performance of religious ceremonies. All these are represented in the embroidery of the robes. They are lightly cut, and it is not improbable that they were originally coloured. The bracelets, armlets, and other ornaments are equally elegant and elaborate in design. In front of the king stands an eunuch, holding in one hand and above the cup, a fly-flapper; and in the other the cover or the case of the cup which is in the hand of the king. A piece of embroidered linen, or a towel, thrown over his shoulder, is ready to be presented to the king, as is the custom to this day in the East, after drinking or performing ablutions. Behind the eunuch is a winged figure wearing the horned-cap, and bearing the fir-cone and basket. At the back of the throne are two eunuchs, carrying the arms of the king, followed by a second winged human figure. The garments and ornaments of all these persons are as richly embroidered, and adorned, as those of the monarch. The colours still adhere to the sandals, brows, hair, and eyes. The sculptures are in the best state of preservation; the most delicate carvings are still distinct, and the outline of the figures retains its original sharpness. Across the slabs runs the customary inscription.12 The Arabs marvelled at these strange figures. As each head was uncovered they showed their amazement by extravagant gestures, or exclamations of surprise. If it was a bearded man, they concluded at once that it was an idol or a Jin, and cursed or spat upon it. If an eunuch, they declared that it was the likeness of a beautiful female, and kissed or patted the cheek. They soon felt as much interest as I did in the objects discovered, and worked with renewed ardour when their curiosity was excited by the appearance of a fresh sculpture. On such occasions they would strip themselves almost naked, throw the handkerchief from their heads, and letting their matted hair stream in the wind, rush like madmen into the trenches, and carry off the baskets of earth, shouting, at the same time, the war cry of the tribe. On the other uncovered slabs of chamber G were groups composed of the king, raising the cup, and attended by two eunuchs, or holding a bow in one hand, and two arrows in the other, preceded and followed by a winged human figure similar to those on Nos. 2. and 4. These groups were alternate, and were all equally remarkable for the richness and elegance of the embroidery and ornaments. They furnished me not only with a collection of beautiful designs, but also with many new and highly interesting symbolical and mythic signs, and figures. I shall hereafter describe these more in detail, and show the important insight they afford us into the religious system of the Assyrians, and the origin of the mythology of some other countries. I did not, for the time, follow the eastern wall of this chamber, but turned into the entrance e, which led me into another chamber (H). This entrance was formed by two winged figures (Nos. 1. and 2.), and two plain slabs (Nos. 3. and 4.) crossed in the centre by the usual inscription. Upon the first slab beyond it, was a winged human figure with a fillet round the temples, carrying the fir-cone and basket; upon the following slabs, the king holding a cup, between two similar winged figures. I quitted this chamber, after uncovering the upper part of four or five bas-reliefs; and returning to the entrances (chamber G), traced to the south of it two slabs upon which were groups similar to those on the opposite wall, except that the right hand of the king rested on the hilt of his sword, and not on the bow. On No. 27. was an eagle-headed figure, and beyond it was discovered another pair of human-headed lions, smaller than those forming entrance a of chamber B, but excelling them in the preservation of the details. The slabs on which they were carved were slightly cracked; but otherwise they appeared to have issued but the day before, from the hand of the sculptor. The accumulation of earth and rubbish above this part of the ruins was very considerable, and it is not improbable that it was owing to this fact that the sculptures had been so completely guarded from injury. Beyond this entrance were continued groups, similar to those already described as occurring on the previous slabs. I was now anxious to embark and forward to Baghdad, or Busrah, for transport to Bombay, such sculptures as I could move with the means at my disposal. Major Rawlinson had obligingly proposed that, for this purpose, the small steamer navigating the lower part of the Tigris should be sent up to Nimroud, and I expected the most valuable assistance, both in removing the slabs and in plans for future excavations, from her able commander, Lieutenant Jones. The Euphrates, one of the two vessels originally launched on the rivers of Mesopotamia, had some years previously succeeded in reaching the tomb of Sultan Abdallah, a few miles below Nimroud. Here impediments, not more serious than those she had already surmounted, occurring in the bed of the stream, she returned to Bagdad. A vessel even of her construction, and with her engines, could have reached, I have little doubt, the bund or dam of the Awai, which would probably have been a barrier to a further ascent of the Tigris. It was found, however, that the machinery of the Nitocris was either too much out of repair, or not sufficiently powerful to impel the vessel over the rapids, which occur in some parts of the river. After ascending some miles above Tekrit the attempt was given up, and she returned to her station. Without proper materials it was impossible to move either the gigantic lions, or even the large sculptures of chamber G. The few ropes to be obtained in the country were so ill-made that they could not support any considerable weight. I determined, therefore, to displace the slabs (in chamber B) divided into two compartments; then to saw off the sculptures, and to reduce them as much as possible by cutting from the back. The inscriptions being mere repetitions, I did not consider it necessary to preserve them, as they added to the weight. With the help of levers of wood, and by digging away the wall of sun-dried bricks from behind the slabs, I was enabled to turn them into the centre of the trench, where they were sawn by marble- cutters from Mosul. When the bas-reliefs were thus prepared, there was no difficulty in dragging them out of the trenches. The upper part of a slab in chamber G, containing the heads of a king and his attendant eunuch, having been discovered broken off from the lower, it was included amongst the sculptures to be embarked. One of the winged figures from entrance e of the same chamber, and an eagle-headed divinity, were also successfully moved. These, with the head and the hoof of the bull in yellow limestone from entrance b chamber B, form the collection first sent to England, and now deposited in the British Museum. As they have been long before the public, and have been more than once accurately described, I need not trouble the reader with any further account of them. After having been removed from the trenches, the sculptures were packed in felts and matting, and screwed down in roughly made cases. They were transported from the mound to the river upon rude buffalo carts belonging to the Pasha, and then placed upon a raft formed of inflated skins and beams of poplar wood. They floated down the Tigris as far as Baghdad, were there placed on hoard boats of the country, and reached Busrah in the month of August. Whilst I was moving these sculptures Tahyar Pasha visited me. He was accompanied, for his better security, by a large body of regular and irregular troops, and three guns. His Diwan Effendesi, seal-bearer, and all the dignitaries of the household, were also with him. I entertained this large company for two days. The Pasha's tents were pitched on an island in the river, near my shed. He visited the ruins, and expressed no less wonder at the sculptures than the Arabs; nor were his conjectures as to their origin and the nature of the subjects represented, much more rational than those of the sons of the desert. The gigantic human-headed lions terrified, as well as amazed, his Osmanli followers. "La Illahi il Allah (there is no God but God)," was echoed from all sides. " These are the idols of the infidels," said one more knowing than the rest. " I saw many such when I was in Italia with Reshid Pasha, the ambassador. Wallah, they have them in all the churches, and the Papas (priests) kneel and burn candles before them." " No, my lamb," exclaimed a more aged and experienced Turk. " I have seen the images of the infidels in the churches of Beyoglu; they are dressed in many colours; and although some of them have wings, none have a dog's body and a tail; these are the works of the Jin, whom the holy Solomon, peace be upon him! reduced to obedience and imprisoned under his seal." " I have seen something like them in your apothecaries' and barbers' shops," said T, alluding to the well-known figure, half woman and half lion, which is met with so frequently in the bazars of Constantinople. " Istafer Allah (God forbid)," piously ejaculated the Pasha; " that is the sacred emblem of which true believers speak with reverence, and not the handywork of infidels." " There is no infidel living," exclaimed the engineer, who was looked up to as an authority on these subjects, " either in Frangistan or in Yenghi Dunia (America), who could make any thing like that; they are the work of the Majus (Magi), and are to be sent to England to form the gateway to the palace of the Queen." " May God curse all infidels and their works! " observed the cadi's deputy, who accompanied the Pasha; " what comes from their hands is of Satan: it has pleased the Almighty to let them be more powerful and ingenious than the true believers in this world, that their punishment and the reward of the faithful may be greater in the next." The heat had now become so intense that my health began to suffer from continual exposure to the sun, and from the labour of superintending the excavations, drawing the sculptures, and copying the inscriptions. In the trenches, where I daily passed many hours, the thermometer generally ranged from 112° to 115° in the shade, and on one or two occasions even reached 117°. The hot winds swept over the desert; they were as blasts from a furnace during the day, and even at night they drove away sleep. I resolved, therefore, to take refuge for a week in the sardaubs or cellars of Mosul; and, in order not to lose time, to try further excavations in the Mound of Kouyunjik. Leaving a superintendent, and a few guards to watch over the uncovered sculptures, I rode to the town. The houses of Baghdad and Mosul are provided with underground apartments, in which the inhabitants pass the day during the summer months. They are generally ill-lighted, and the air is close and oppressive. Many are damp and unwholesome; still they offered a welcome retreat during the hot weather, when it was almost impossible to sit in a room. At sunset the people emerge from these subterraneous chambers and congregate on the roofs, where they spread their carpets, eat their evening meal, and pass the night. After endeavouring in vain for some time to find any one who had seen the bas-relief, described by Rich13 as having been found in one of the mounds forming the large quadrangle in which are included Nebbi Yunus and Kouyunjik, an aged stone-cutter presented himself, and declared that he had not only been present when the sculpture was discovered, but that he had been employed to break it up. He offered to show me the spot, and I opened a trench at once into a high mound which he pointed out in the northern line of ruins. The workmen were not long in coming upon fragments of sculptured alabaster, and after two or three days' labour an entrance was discovered, formed by two winged figures, which had been purposely destroyed. The legs and the lower part of the tunic were alone preserved. The proportions were gigantic, and the relief higher than that of any sculpture hitherto discovered in Assyria. This entrance led into a chamber, of which slabs about five feet high and three broad alone remained standing. There were marks of the chisel over them all; but from their size, it appeared doubtful whether figures had ever been sculptured upon them. As no slabs of alabaster or fragments of the same material were found, it is probable that the upper part of the walls was constructed of kiln-burnt bricks, with which the whole chamber was filled up, and which indeed formed the greater part of the mound. On the sides of many of them was an inscription, containing the name of the king who built the edifices of which Kouyunjik and Nebbi Yunus are the remains. The pavement was of limestone. After tracing the walls of one chamber, I renounced a further examination, as no traces of sculpture were to be found, and the accumulation of rubbish was very considerable. This building appears to have been either a guardhouse at one of the entrances into the quadrangle, or a tower defending the walls. From the height of the mound it would seem that there were two or more stories. The comparative rest obtained in Mosul so far restored my strength, that I returned to Nimroud in the middle of August, and again attempted to renew the excavations. I uncovered the top of the slabs of chamber H from entrance e to entrance b, and discovered the chambers I and R.14 Upon most of them were similar sculptures; the king standing between two winged figures, and holding in one hand a cup, in the other a bow. The only new feature in this chamber was a recess cut out of the upper part of slab No. 3. I am at a loss to account for its use; from its position it might have been taken for a window, opening into chamber G; but there was no corresponding aperture in the slab, which formed the facing of the wall at its back in that chamber. It may have been used as a place of deposit for sacred vessels and instruments, or as an altar for sacrifice; a conjecture which may be strengthened by the fact of a large square stone, slightly hollowed in the centre, and probably meant to contain a fluid, being generally found in front of the slabs in which such recesses occur. The slabs in chamber R were unsculptured, having the usual inscription across them. The pavement was formed by alabaster slabs. Entrance b led me into a further chamber, narrow and long in its proportions. I only uncovered the upper part of a few of the slabs. Upon them were two bas-reliefs, separated by the usual inscription; the upper (similar on all the slabs) represented two winged human figures with the horned cap, kneeling on one knee before the mystic tree; their hands are stretched out. one towards the top, and the other towards the bottom of the emblem before them. In the lower compartments were eagle-headed figures facing each other in pairs, and separated by the same symbol. The state of my health again compelled me to renounce for the time my labours at Nimroud. As I required a cooler climate, I determined to visit the Tiyari mountains, inhabited by the Chaldæan Christians, and to return to Mosul in September, when the violence of the heat had abated.

|

|

|

|

|

1) All these objects will be deposited in the British Museum. 2) This head may have belonged to the end of a chariot pole, or may have cased the head of the bull or ram carried by the winged lion, at the feet of which it was discovered. 3) Storms of this nature are frequent during the early part of summer throughout Mesopotamia, Babylonia, and Susiana. It is difficult to convey an idea of their violence. They appear suddenly and without any previous sign, and seldom last above an hour. It was during one of them that the Tigris steamer, under the command of Colonel Chesney, was wrecked in the Euphrates; and so darkened was the atmosphere that, although the vessel was within a short distance of the bank of the river, several persons who were in her are supposed to have lost their lives from not knowing in what direction to swim. 4) Chamber B, plan 3. 5) This bas-relief will be placed in the British Museum. 6) Entrance A, chamber B, plan 3. 7) A similar object is seen in the hand of a sitting figure on a cylinder, engraved in Rich's Second Memoir on Babylon. 8) This bas-relief has been sent to England: it is broken in several pieces. 9) Entrance c, chamber B, plan 3. 10) In the rock sculptures of Bavian, to the east of Mosul, they occur above the king, and they are frequently found on cylinders, 11) From slab No. 1. to 8. 12) The three slabs with these bas-reliefs are on their way to England. 13) Residence In Kurdistan and Nineveh, vol. ii. p. 39. 14) Plan 3.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD