Nineveh and Its Remains

Volume 1

By Austen Henry Layard, ESQ. D.C.L.

Part 1- Chapter 3

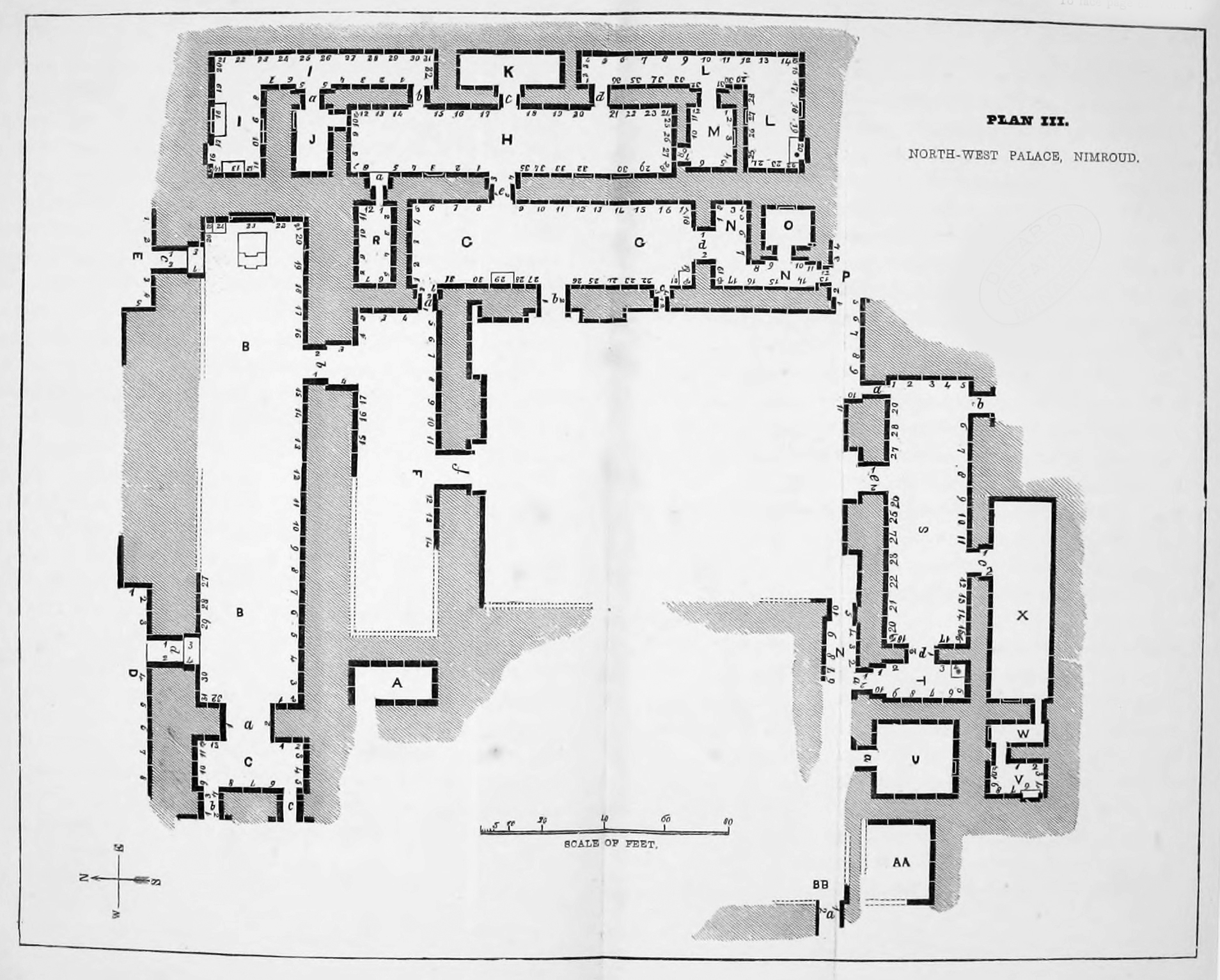

On my return to Mosul in the beginning of January, I found Ismail Pasha installed in the government. He received me with courtesy, offered no opposition to the continuation of my researches at Nimroud, and directed the irregular troops stationed at Selamiyah to afford me every assistance and protection. The change since my departure had been as sudden as great. A few conciliatory acts on the part of the new Governor, an order from the Porte for an inquiry into the sums unjustly levied by the late Pasha, with a view to their repayment, and a promise of a diminution of taxes, had so far reassured and gained the confidence of those who had fled to the mountains and the desert, ihat the inhabitants of the villages were slowly returning to their homes; and even the Arab tribes, which were formerly accustomed to pasture their flocks in the districts of Mosul, were again pitching their tents on the banks of the Tigris. The diminished population of the province had been so completely discouraged by the repeated extortions of Keritli Oglu, that the fields had been left untilled. The villagers were now actively engaged, although the season was already far advanced, in sowing grain of various kinds. The palace was filled with Kurdish chiefs and Arab Sheikhs, who had accepted the invitation of the new Pasha to visit the town, and were seeking investiture as heads of their respective tribes. The people of Mosul were looking forward to an equal taxation, and the abolition of the system of torture and arbitrary exactions, which had hitherto been adopted by their governors. During my absence my agents had not been inactive. Several trenches had been opened in the great mound of Baasheikha; and fragments of sculpture and inscriptions, with much entire pottery and inscribed bricks, had been discovered there. At Karamies a platform of brickwork had been uncovered, and the Assyrian origin of the ruin was proved by the inscription on the bricks, which contained the name of the Khorsabad king. I rode to Nimroud on the 17th of January, having first engaged a party of Nestorian Chaldeans to accompany me. The change that had taken place in the face of the country during my absence, was no less remarkable than that which I had found in the political state of the province. To nie they were both equally agreeable and welcome. The rains, which had fallen almost incessantly from the day of my departure for Baghdad, had rapidly brought forward the vegetation of spring. The mound was no longer an arid and barren heap; its surface and its sides were equally covered with verdure. From the summit of the pyramid my eye ranged, on one side, over a broad level enclosed by the Tigris and the Zab; on the other, over a low undulating country bounded by the snow-capped mountains of Kurdistan; but it was no longer the dreary waste' I had left a month before; the landscape was clothed in green, the black tents of the Arabs chequered the plain of Nimroud, and their numerous flocks pastured on the distant hills. The Abou Salman, encourao;ed by favourable reports of the policy of the new Pasha, had recrossed the Zab, and had sought their old encamping grounds. The Jehesh and Shemutti Arabs had returned to their villages, around which the wandering" Jebours had pitched their tents, and were now engaged in cultivating the soil. Even on the mound the plough opened its furrows, and corn was sown over the palaces of the Assyrian kings. Security had been restored, and Nimroud offered a more convenient and more agreeable residence than Selamiyah. Hiring, therefore, from the owners three huts, which had been hastily built in the outskirts of the village, I removed to my new dwelling place. A few rude chairs, a table, and a wooden bedstead, formed the whole of my furniture. My Cawass spread his carpet, and hung his tobacco pouch in the corner of a hovel, which he had appropriated, and spent his clays in peaceful contemplation. The servants constructed a rude kitchen, and the grooms shared the stalls with the horses. Mr, Hormuzd Eassam, the brother of the British Vice-Consul, came to reside with me, and undertook the daily payment of the workmen and the domestic arrangements. My agent, with the assistance of the chief of the Hytas, had punctually fulfilled the instructions he had' received on my departure. Not only were the counterfeit graves carefully removed, but even others, which possessed more claim to respect, had been rooted out. I entered into an elaborate argument with the Arabs on the subject of the latter, and proved to them that, as the bodies were not turned towards Mecca, they could not be those of true believers. I ordered the remains, however, to be carefully collected, and to be reburied at the foot of the mound. I had now uncovered the back of the whole of wall j, of wall k to slab 15, and of six slabs of wall m; Nos. 1. and 2. of wall f, and the entrance d with a small part of wall a. All these belonged to the palace in the S. W. corner of the mound represented by plan 2. In the centre of the mound I had discovered the remains of the two winged bulls; in the N. W. palace, figured in plan 3., the chamber A, and the two small winged lions forming the entrance to chamber BB. The only additional bas-reliefs were two on slab 12 of wall k (plan 2.), the upper much injured and the subject unintelligible; the lower containing four figures, carrying presents or supplies for a banquet. The hands of the foremost figure having been destroyed, the object which they held could not be determined. The secon-1 bears either fruit or a loaf of bread, the third has a basket in his right hand, whilst the left holds a skin of wine thrown over the shoulder, and the fourth is the bearer of a similar skin, having in the right hand a vessel of not inelegant shape. The four figures are •clothed in long robes, richly fringed, descending to the ankles, and wear the conical cap or helmet before described. The slab on which these bas-reliefs occurred had also been reduced in size, to the injury of the sculpture, and had evidently belonged to another building. The slabs on either side of it bore the usual inscription. I had scarcely resumed my labours when I received information that the Cadi of Mosul was endeavouring to stir up the people against me, chiefly on the plea that I was carrying away treasure; and, what was worse, finding inscriptions which proved that the Franks once held the country, and upon the evidence of which they intended immediately to resume possession of it, exterminating all true believers. These stories, however absurd they may appear, rapidly gained ground in the town. Old Mohanmied Emin Pasha brought out his Yakuti, and confirmed, by that geographer's statements with regard to Khorsabad, the allegations of the Cadi. A representation was ultimately made by the Ulema to Ismail Pasha; and as he expressed a wish to see me, I rode to Mosul. He was not, he said, influenced by the Cadi or the Mufti, nor did he believe the absurd tales which they had spread abroad I should shortly see how he intended to treat these troublesome fellows, but he thought it prudent at present to humour them, and made it a personal request that I would, for the time, suspend the excavations. I consented with regret; and once more returned to Nimroud without being able to gratify the ardent curiosity I felt to explore further the extraordinary building, the nature of which was still a mystery to me. The Abou Salman Arabs, who encamp around Nimroud, are known for their thieving propensities, and might have caused me some annoyance. Thinking it prudent, therefore, to conciliate their chief, I rode over one morning to their principal encampment. Sheikh Abd-ur-rahman received me at the entrance of his capacious tent of black goat-hair, which was crowded with his relations, followers, and strangers, who were enjoying his hospitality. He was one of the handsomest Arabs I ever saw; tall, robust, and well-made, with a countenance in which intelligence was no less marked than courage and resolution. On his head he wore a turban of dark linen, from under which a many-coloured handkerchief fell over his shoulders; his dress was a simple white shirt, descending to the ankles, and an Arab cloak thrown loosely over it. Unlike Arabs in general, he had shaved his beard; and, although he could scarcely be much beyond forty, I observed that the little hair which could be distinguished from under his turban was grey. He received me with every demonstration of hospitality, and led me to the upper place, divided by a goat-hair curtain from the harem. The tent was capacious; half was appropriated by the women, the rest formed the place of reception, and was at the same time occupied by two favourite mares and a colt. A few camels were kneeling on the grass around, and the horses of the strangers were tied by the halter to the tent-pins. From the carpets and cushions, which were spread for me, stretched on both sides a long line of men of the most motley appearance, seated on the bare ground. The Sheikh himself, as is the custom in some of the tribes, to show his respect for his guest, placed himself at the furthest end; and could only be prevailed upon, after many excuses and protestations, to share the carpet with me. In the centre of the group, near a small fire of camel's dung, crouched a half-naked Arab, engaged alternately in blowing up the expiring embers, or pounding the roasted coffee in a copper mortar, ready to replenish the huge pots which stood near him. After the customary compliments had been exchanged with all around, one of my attendants beckoned to the Sheikh, who left the tent to receive the presents I had brought to him, — a silk gown and a supply of coffee and sugar. He dressed himself in his new attire and returned to the assembly. " Inshallah," said I, " we are now friends, although scarcely a month ago you came over the Zab on purpose to appropriate the little property I am accustomed to carry about me." "Wallah, Bey," he replied, " you say true, we are friends; but listen: the Arabs either sit down and serve his Majesty the Sultan, or they eat from others, as others would eat from them. Now my tribe are of the Zobeide, and were brought here many years ago by the Pashas of the Abd-el-Jelleel.1 These lands were given us in return for the services we rendered the Turks in keeping back the Tai and the Shammar, who crossed the rivers to plunder the villages. All the great men of the Abou Salman perished in encounters with the Bedouin, and Injeh Bairakdar, Mohammed Pasha, upon whom God has had mercy, acknowledged our fidelity and treated us with honour. When that blind dog, the son of the Cretan, may curses fall upon him! came to Mosul, I waited upon him, as it is usual for the Sheikh; what did he do? Did he give me the cloak of honour? No; he put me, an Arab of the tribe of Zobeide, a tribe which had fought with the Prophet, into the public stocks. For fortv days my heart melted away in a damp cell, and I was exposed to every variety of torture. Look at these hairs," continued he, lifting up his turban, " they turned white in that time, and I must now shave my beard, a shame amongst the Arabs. I was released at last; but how did I return to the tribe? — a beggar, unable to kill a sheep for my guests. He took my mares, my flocks, and my camels, as the price of my liberty. Now tell me, O Bey, in the name of God, if the Osmanlis have eaten from me and my guests, shall I not eat from them and theirs?" The fate of Abd-ur-rahman had been such as he described it; and so had fared several chiefs of the desert and of the mountains. It was not surprising:; that these men, proud, of their origin and accustomed to the independence of a wandering life, had revenged themselves upon the unfortunate inhabitants of the villages, who had no less cause to complain than themselves. However, the Sheikh promised to abstain from plunder for the future, and to present himself to Ismail Pasha, of whose conciliatory conduct he had already heard. It was nearly the middle of February before I thought it prudent to make fresh experiments among the ruins. To avoid notice I only employed a few men, and confined myself to the examination of such parts of the mound as appeared to contain buildings. A trench was first opened at right angles to the centre of wall k (plan 2.), and we speedily found the wall q. All the slabs were sculptured, and uninjured by fire; but unfortunately had been half destroyed by long exposure to the atmosphere. Three consecutive slabs were occupied by the same subject; others were placed without regularity, portions of a figure, which should have been continued on an adjoining stone, being wanting. It was evident from the costume, the ornaments, and the nature of the relief, that these sculptures did not belong either to the same building, or to the same period as those previously discovered. I recognised in them the style of Khorsabad, and in the inscriptions particular forms in the character, which were used in the inscriptions of that monument. Still the slabs were not "in situ:" they had been brought from elsewhere, and I was even more perplexed than I had hitherto been. The most perfect of the bas-reliefs (No. 1.) was in many respects interesting. It represented a king, distinguished by his high conical tiara, standing over a prostrate warrior; his right hand elevated, and the left supported by a bow. The figure at his feet, probably a captive enemy or rebel, wore a pointed cap, somewhat similar in form to that already described. I was, from this circumstance, at first inclined to believe that the sculpture represented the conquest of the original founders of Nimroud, by a new race, — perhaps the overthrow of the first by the second Assyrian dynasty; but I was subsequently led to abandon the conjecture. An eunuch holds a fly-flapper or fan over the head of the king, who appears to be conversing or performing some ceremony with a figure standing in front of him; probably his vizir or minister.2 Behind this personage, who differs from the King by his head-dress, — a simple fillet round the temple, — are two attendants, the first an eunuch, the second a bearded figure, half of which was continued on the adjoining slab. This bas-relief was separated from a second above, by a band of inscriptions; the upper sculpture was almost totally destroyed, and I could with difficulty trace upon it the forms of horses, and horsemen. A wounded figure beneath the horses wore a helmet with a curved crest, resembling the Greek. These two subjects were continued on either side, but the slabs were broken off near the bottom, and the feet of a row of figures, probably other attendants, standing behind the king and his minister, could only be distinguished. Another slab in this wall (No. 3.) was occupied, with the exception of the prisoner, by figures resembling those on the slab just described. The king, however, holds his bow horizontally, and his attendant eunuch is carrying his arms, a second bow, the mace, and a quiver. All these figures are about three feet eight inches in height, the dimensions of those before discovered being somewhat smaller. The rest of the wall, which had completely disappeared in some places, was composed of gigantic winged figures, sculptured in low relief. They were found to be almost entirely defaced. Several trenches carried to the west of wall q, and at right angles with it, led me to walls s and t. The sculptured slabs, of which they were built, were not better preserved than others in this part of the mound. I could only distinguish the lower part of gigantic figures; some had been purposely defaced by a sharp instrument; others, from long exposure, had been worn almost smooth. Inscriptions were carried across the slabs over the drapery, but were interrupted when a naked limb occurred, and resumed beyond it. Such is generally the case when, as in the older palace of Nimroud, inscriptions are engraved over a figure. These experiments were sufficient to prove that the building I was exploring had not been entirely destroyed by fire, but had been partly exposed to gradual decay. No sculptures had hitherto been discovered in a perfect state of preservation, and only one or two could bear removal. I determined, therefore, to abandon this corner, and to resume excavations near the chamber first opened3, where the slabs had in no way been injured. The workmen were directed to dig behind the small lions4, which appeared to form an entrance, and to be connected with other walls. After removing much earth, a few un sculptured slabs were discovered, fallen from their places, and broken in many pieces. The sides of the room of which they had originally formed part could not be traced. As these ruins occurred on the edge of the mound, it was probable that they had been more exposed than the rest, and consequently had sustained more injury than other parts of the building. As there was a ravine running far into the mound, apparently formed by the winter rains, I determined to open a trench in the centre of it. In two days the workmen reached the top of a slab, which appeared to be both well preserved, and to be still standing in its original position. On the south side I discovered, to my great satisfaction, two human figures, considerably above the natural size, sculptured in low relief, and still exhibiting all the freshness of a recent work. This was No. 30. of chamber B in the third plan. In a few hours the earth and rubbish had been completely removed from the face of the slab, no part of which had been injured. The ornaments delicately graven on the robes, the tassels and fringes, the bracelets and armlets, the elaborate curls of the hair and beard, were all entire. The figures were back to back, and furnished with wings. They appeared to represent divinities, presiding over the seasons, or over particular religious ceremonies. The one, whose face was turned to the East, carried a fallow deer on his right arm, and in his left hand a branch bearing five flowers. Around his temples was a fillet, adorned in front with a rosette. The other held a square vessel, or basket, in the left hand, and an object resembling a fir cone in the right. On his head he wore a rounded cap, at the base of which was a horn. The garments of both, consisting of a stole falling from the shoulders to the ankles, and a short tunic underneath, descending to the knee, were richly and tastefully decorated with embroideries and fringes, whilst the hair and beard were arranged with study and art. Although the relief was lower, yet the outline was perhaps more careful, and true, than that of the Assyrian sculptures of Khorsabad. The limbs were delineated with peculiar accuracy, and the muscles and bones faithfully, though somewhat too strongly, marked. An inscription ran across the sculpture. To the west of this slab, and fitting to it, was a corner-stone ornamented with flowers and scroll-work, tastefully arranged, and resembling in detail those graven on the injured tablet, near entrance d of the S.W. building. I recognised at once from whence many of the sculptures, employed in the construction of that edifice, had been brought; and it was evident that I had at length discovered the earliest palace of Nimroud. The corner-stone led me to a figure of singular form.5 A human body, clothed in robes similar to those of the winged men on the previous slab, was surmounted by the head of an eagle or of a vulture,6 The curved beak, of considerable length, was half open, and displayed a narrow pointed tongue, which was still coloured with red paint. On the shoulders fell the usual curled and bushy hair of the Assyrian images, and a comb of feathers rose on the top of the head. Two wings sprang from the back, and in either hand was the square vessel and fir-cone. On all these figures paint could be faintly distinguished, particularly on the hair, beard, eyes, and sandals. The slabs on which they were sculptured had sustained no injury, and could be without difficulty packed and moved to any distance. There could no longer be any doubt that they formed part of a chamber, and that, to explore it completely, I had only to continue along the wall, now partly uncovered.

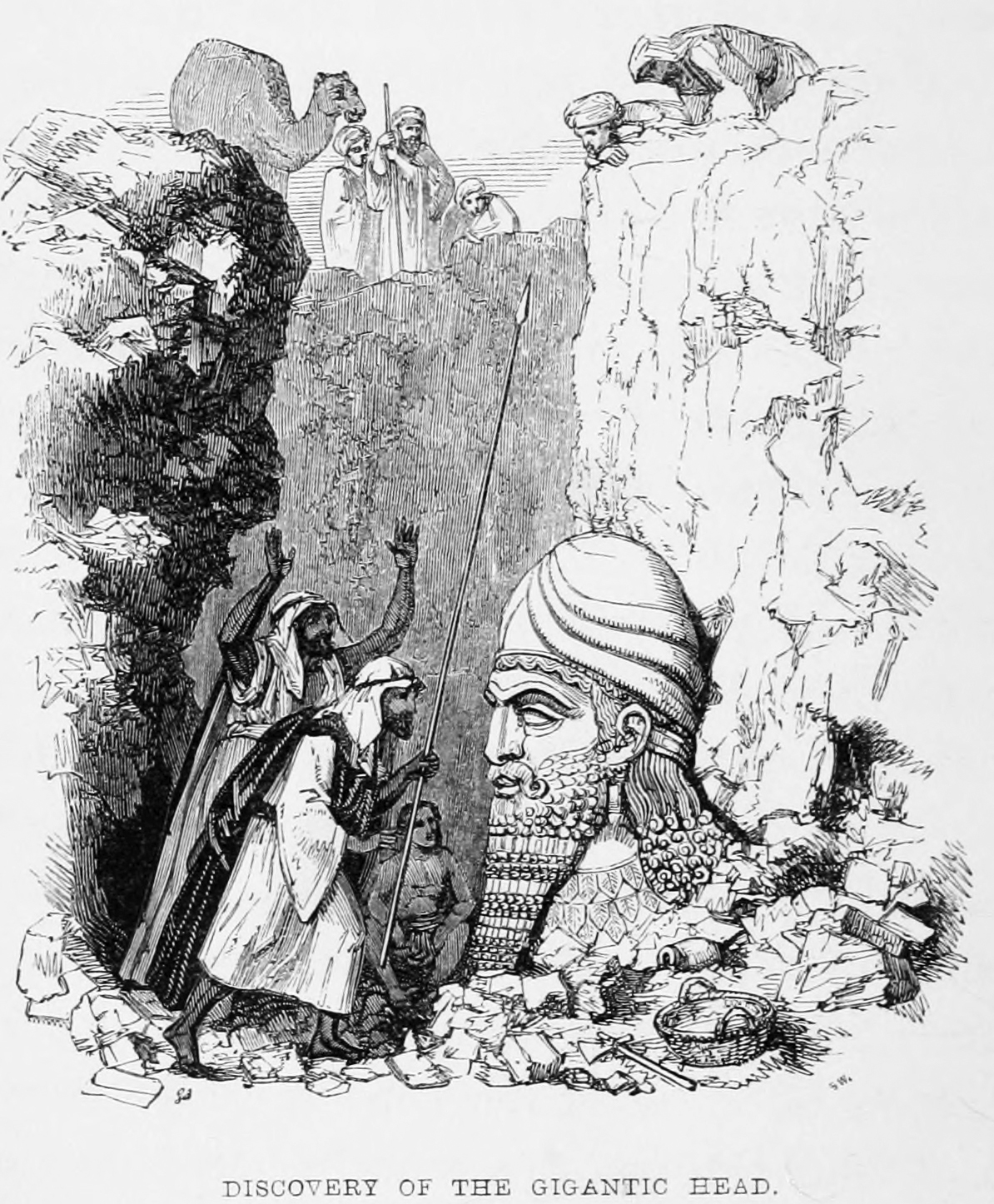

On the morning following these discoveries, I rode to the encampment of Sheikh Abd-ur-rahman, and was returning to the mound, when I saw two Arabs of his tribe urging their mares to the top of their speed. On approaching me they stopped. " Hasten, O Bey," exclaimed one of them — " hasten to the diggers, for they have found Nimrod himself Wallah, it is wonderful, but it is true! we have seen him with our eyes. There is no God but God; " and both joining in this pious exclamation, they galloped off, without further words, in the direction of their tents. On reaching the ruins I descended into the new trench, and found the workmen, who had already seen me, as I approached, standing near a heap of baskets and cloaks. Whilst Awad advanced and asked for a present to celebrate the occasion, the Arabs withdrew the screen they had hastily constructed, and disclosed an enormous human head sculptured in full out of the alabaster of the country. They had uncovered the upper part of a figure, the remainder of which was still buried in the earth. I saw at once that the head must belong to a winged lion or bull, similar to those of Khorsabad and Persepolis. It was in admirable preservation. The expression was calm, yet majestic, and the outline of the features showed a freedom and knowledge of art, scarcely to be looked for in the works of so remote a period. The cap had three horns, and, unlike that of the human-headed bulls hitherto found in Assyria, was rounded and without ornament at the top. I was not surprised that the Arabs had been amazed and terrified at this apparition. It required no stretch of imagination to conjure up the most strange fancies. This gigantic head, blanched with age, thus rising of from the bowels of the earth, might well have belonged to one of those fearful beings which are pictured in the traditions of the country, as appearing to mortals, slowly ascending from the regions below. One of the workmen on catching the first glimpse of the monster, had thrown down his basket and run off towards Mosul as fast as his legs could carry him. I learnt this with regret as I anticipated the consequences. Whilst I was superintending the removal of the earth, which still clung to the sculpture, and giving directions for the continuation of the work, a noise of horsemen was heard, and presently Abd-ur-rahman, followed by half his tribe, appeared on the edge of the trench. As soon as the two Arabs had reached the tents, and published the wonders they had seen, every one mounted his mare and rode to the mound, to satisfy himself of the truth of these inconceivable reports. When they beheld the head they all cried together, " There is no God but God, and Mahommed is his Prophet! " It was some time before the Sheikh could be prevailed upon to descend into the pit, and convince himself that the image he saw was of stone. " This is not the work of men's hands," exclaimed he, " but of those infidel giants of whom the Prophet, peace be with him! has said, that they were higher than the tallest date tree; this is one of the idols which Noah, peace be with him! cursed before the flood." In this opinion, the result of a careful examination, all the bystanders concurred.

I now ordered a trench to be dug due south from the head, in the expectation of finding a corresponding figure, and before night-fall reached the object of my search about twelve feet distant. Engaging two or three men to sleep near the sculptures, I returned to the village and celebrated the day's discovery by a slaughter of sheep, of which all the Arabs near partook. As some wandering musicians chanced to be at Selamiyah, I sent for them, and dances were kept up during the greater part of the night. On the following: morning Arabs from the other side of the Tigris, and the inhabitants of the surrounding villages congregated on the mound. Even the women could not repress their curiosity, and came in crowds, with their children, from afar. My Cawass was stationed during the day in the trench, into which I would not allow the multitude to descend. As I had expected, the report of the discovery of the gigantic head, carried by the terrified Arab to Mosul, had thrown the town into commotion. He had scarcely checked his speed before reaching the bridge. Entering breathless into the bazars, he announced to every one he met that Nimrod had appeared. The news soon got to the ears of the Cadi, who, anxious for a fresh opportunity to annoy me, called the Mufti and the Ulema together, to consult upon this unexpected occurrence. Their deliberations ended in a procession to the Governor, and a formal protest, on the part of the Musulmans of the town, against proceedings so directly contrary to the laws of the Koran. The Cadi had no distinct idea whether the bones of the mighty hunter had been uncovered, or only his image; nor did Ismail Pasha very clearly remember whether Nimrod was a true believing prophet, or an Infidel. I consequently received a somewhat unintelligible message from his Excellency, to the effect that the remains should be treated with respect, and be by no means further disturbed, and that he wished the excavations to be stopped at once, and desired to confer with me on the subject. I called upon him accordingly, and had some difficulty in making him understand the nature of my discovery. As he requested me to discontinue my operations until the sensation in the town had somewhat subsided, I returned to Nimroud and dismissed the workmen, retaining only two men to dig leisurely along the walls without giving cause for further interference. I ascertained by the end of March the existence of a second pair of winged human-headed lions7, differing from those previously discovered in form, the human shape being continued to the waist and furnished with arms. In one hand each figure carried a goat or stag, and in the other, which hung down by the side, a branch with three flowers. They formed a northern entrance into the chamber of which the lions previously described were the southern portal. I completely uncovered the latter, and found them to be entire. They were about twelve feet in height, and the same number in length. The body and limbs were admirably portrayed; the muscles and bones, although strongly developed to display the strength of the animal, showed at the same time a correct knowledge of its anatomy and form. Expanded wings sprung from the shoulder and spread over the back; a knotted girdle, ending in tassels, encircled the loins. These sculptures, forming an entrance, were partly in full and partly in relief. The head and fore-part, facing the chamber, were in full; but only one side of the rest of the slab was sculptured, the back being placed against the wall of sun-dried bricks. That the spectator might have both a perfect front and side view of the figures, they were furnished with five legs; two were carved on the end of the slab to face the chamber, and three on the side. The relief of the body and three limbs was high and bold, and the slab was covered, in all parts not occupied by the image, with inscriptions in the cuneiform character. These magnificent specimens of Assyrian art were in perfect preservation; the most minute lines in the details of the wings and in the ornaments had been retained with their original freshness. Not a character was wanting in the inscriptions. I used to contemplate for hours these mysterious emblems, and muse over their intent and history. What more noble forms could have ushered the people into the temple of their gods? What more sublime images could have been borrowed from nature, by men who sought, unaided by the light of revealed religion, to embody their conception of the wisdom, power, and ubiquity of a Supreme Being? They could find no better type of intellect and knowledge than the head of the man; of strength, than the body of the lion; of rapidity of motion, than the wings of the bird. These winged human-headed lions were not idle creations, the offspring of mere fancy; their meaning was written upon them. They had awed and instructed races which flourished 3000 years ago. Through the portals which they guarded, kings, priests, and warriors, had borne sacrifices to their altars, long before the wisdom of the East had penetrated to Greece, and had furnished its mythology with symbols long recognised by the Assyrian votaries. They may have been buried, and their existence may have been unknown, before the foundation of the eternal city. For twenty-five centuries they had been hidden from the eye of man, and they now stood forth once more in their ancient majesty. But how changed was the scene around them! The luxury and civilisation of a mighty nation had given place to the wretchedness and ignorance of a few half-barbarous tribes. The wealth of temples, and the riches of great cities, had been succeeded by ruins and shapeless heaps of earth. Above the spacious hall in which they stood, the plough had passed and the corn now waved. Egypt has monuments no less ancient and no less wonderful; but they have stood forth for ages to testify her early power and renown; whilst those before me had but now appeared to bear witness in the words of the prophet, that once " the Assyrian was a cedar in Lebanon with fair branches and with a shadowing shroud of an high stature; and his top was among the thick boughs. . . . his height was exalted above all the trees of the field, and his boughs were multiplied, and his branches became long, because of the multitude of waters when he shot forth. All the fowls of heaven made their nests in his boughs, and under his branches did all the beasts of the held bring forth their young, and under his shadow dwelt all great nations; " for now is " Nineveh a desolation and dry like wilderness, and flocks lie down in the midst of her: all the beasts of the nations, both the cormorant and bittern, lodge in the upper lintels of it; their voice sings in the windows; and desolation is in the thresholds."8 Behind the lions was another chamber,9 I uncovered about fifty feet of its northern wall. On each slab was carved the winged figure with the horned cap, fir-cone, and square vessel or basket. They were in pairs facing one another and divided by an emblematic tree, similar to that on the corner stone in chamber B. All these bas-reliefs were inferior in execution, and finish, to those previously discovered. During the month of March I received visits from the principal Sheikhs of the Jebour Arabs, whose tribes had now partly crossed the Tigris, and were pasturing their flocks in the neighbourhood of Nimroud, or cultivating millet on the banks of the river. The Jebour are a branch of the ancient tribe of Obeid. Their encamping grounds are on the banks of the Khabour, from its junction with the Euphrates, — from the ancient Carchemish or Circesium, — to its source at Eas-el-Ain. They were suddenly attacked and plundered a year or two ago by the Aneyza; and being compelled to leave their haunts, took refuge in the districts around Mosul. The Pasha, at first, received them well; but learning that several mares of pure Arab blood still remained with the Sheikhs, he determined to seize them. To obtain them as presents, or by purchase, he knew to be impossible; he consequently formed the design of taking the tribe by surprise, as they had been thrown off their guard by their friendly reception. A body of irregular troops was accordingly sent for the purpose towards their tents; but the Arabs, suspecting the nature of their visit, prepared to resist. A conflict ensued in which the Pasha's horsemen were completely defeated. A more formidable expedition, including regular troops and artillery, now marched against them. But they were again victorious and repulsed the Turks with considerable loss. They fled, nevertheless, to the desert, where they had since been wandering in great misery, joining with the Shammar and other tribes in plundering the villages of the Pashalic. On learning the measures taken by Ismail Pasha, dying with hunger, they had returned to arable lands on the banks of the river; where, by an imperfect and toilsome fashion of irrigation, they could, during the summer months, raise a small supply of millet to satisfy their immediate necessities. The Jebour were at this time divided into three branches, obeying different Sheikhs. The names of the three chiefs were Abd'rubbou, Mohammed Emin, and Mohammed ed Dagher. Although all three visited me at Nimroud, it was the first with whom I was best acquainted, and who rendered me most assistance. I thought it necessary to give them each small presents, a silk dress, or an embroidered cloak, with a pair of capacious boots, as in case of any fresh disturbances in the country it would be as well to be on friendly terms with the tribe. The intimacy, however, which sprang from these acts of generosity, was not in all respects of the most desirable or convenient nature. The Arab compliment of" my house is your house " was accepted more literally than I had intended, and I was seldom free from a large addition to my establishment. A Sheikh and a dozen of his attendants were generally installed in my huts, whilst their mares were tied at every door. My fame even reached the mountains, and one day, on returning from Mosul, I found a Kurdish chief, with a numerous suite, in the full enjoyment of my premises. The whole party were dressed in the height of fashion. Every colour had received due consideration in their attire. Their arms were of very superior design and workmanship, their turbans of adequate height and capacity. The chief enjoyed a multiplicity of titles, political, civil, and ecclesiastical: he was announced as Mullah Ali Effendi Bey10; and brought, as a token of friendship, a skin of honey and cheese, a Kurdish carpet, and some horse trappings. I felt honoured by the presence of so illustrious a personage, and the duties of hospitality compelled me to accept his offerings, which were duly placed amongst the stores. He had evidently some motives sufficiently powerful to overcome his very marked religious prejudices — motives which certainly could not be traced to disinterested" friendship. Like Shylock, he would have said, had he not been of too good breeding, " I will buy with you, sell with you, talk with you, walk with you, and so following; but I will not eat with you, drink with you, nor pray with you; " for he sat in solitary sanctity to eat his own pillaf, drank out of a reserved jar, and sought the dwellings of the true believers to spread his prayer-carpet. Dogs were an abomination to him, and two of his attendants were constantly on the watch to keep his legs and the lower part of his garments free from the touch of my greyhounds, who wandered through the premises. As my guest was the chief of a large tribe of nomad Kurds who inhabit the mountains in the neighbourhood of Rowandiz during the summer, and the plains around Arbil in winter, I did not feel the necessity of conciliating him as I had done the Arab Sheikhs encamping near Nimroud, nor did I desire to encourage visits from persons of his sanctity and condition. I allowed him therefore to remain without making any return for his presents, or understanding the hints on the subject he took frequent occasion to drop. At length, on the second evening, his secretary asked for an interview. " The Mullah Effendi," said he, " will leave your Lordship's abode to-morrow. Praise be to God, the most disinterested and sincere friendship has been established between you, and it is suitable that your Lordship should take this opportunity of giving a public testimony of your regard for his Reverence. Not that he desires to accept anything from you, but it would be highly gratifying to him to prove to his tribe that he has met with a friendly reception from so distinguished a person as yourself, and to spread through the mountains reports of your generosity." " I regret," answered I, "that the trifling differences in matters of religion which exist between us, should preclude the possibility of the Effendi's accepting anything from me; for I am convinced that, however amiable and friendly he may be, a man of his sanctity would not do anything forbidden by the law. I am at a loss, therefore, to know how I can meet his wishes." " Although," he rejoined, " there might perhaps be some difficulty on that score, yet it could be, I hope, overcome. Moreover, there are his attendants; they are not so particular as he is, and, thank God, we are all one. To each of them you might give a pair of yellow boots and a silk dress; besides, if you chance to have any pistols or daggers, they would be satisfied with them. As for me, I am a man of letters, and, having nothing to do with arms and boots, you might, therefore, show your approbation of my devotedness to your service, by giving me white linen for a turban, and a pair of breeches. The Eifendi, however, would not object to a set of razors, because the handles are of ivory and the blades of steel; and it is stated in the Hadith that those materials do not absorb moisture11; besides, he would feel obliged if you could lend him a small sum — five purses, for instance, (Wallah, Billah, Tillah he would do the same for you at any time,) for which he would give you a note of hand." "It is very unfortunate," I replied, " that there is not a bazar in the village. I will make a list of all the articles you specify as proper to be given to the attendants and to yourself. But these can only be procured in Mosul, and two days would elapse before they could reach me. I could not think of taking up so much of the valuable time of the Mullali Effendi, whose absence must already have been sorely felt by his tribe. with regard to the money, for which, God forbid that I should think of taking any note of hand (praise be to God! we are on much too good terms for such formalities), and to the razors, I think it would give more convincing proof of my esteem for the Effendi, if I were myself to return his welcome visit, and be the bearer of suitable presents." Finding that a more satisfactory answer could not be obtained, the secretary retired with evident marks of disappointment in his face. A further attempt was made upon Mr. Hormuzd Rassam, and renewed again in the morning; but nothing more tangible could be procured. After staying four days, the Mullah Effendi Bey and his attendants, about twenty in number, mounted their horses and rode away. I was no more troubled with visits from Kurdish Chiefs. The middle of March in Mesopotamia is the brightest epoch of spring. A new change had come over the face of the plain of Nimroud. Its pasture lands, known as the "Jaif," are renowned for their rich and luxuriant herbage. In times of quiet, the studs of the Pasha and of the Turkish authorities, with the horses of the cavalry and of the inhabitants of Mosul, are sent here to graze. Day by day they arrived in longlines. The Shemutti and Jehesh left their huts, and encamped on the greensward which surrounded the villages. The plain, as far as the eye could reach, w^as studded with the white pavilions of the H3'tas and the black tents of the Arabs. Picketed around them were innumerable horses in gay trappings, struggling to release themselves from the bonds, which restrained them from ranging over the green pastures. Flowers of every hue enamelled the meadows; not thinly scattered over the grass as in northern climes, but in such thick and gathering: clusters that the whole plain seemed a patchwork of many colours. The dogs, as they returned from hunting, issued from the long grass dyed red, yellow or blue, according to the flowers through which they had last forced their way. The villages of Naifa and Nimroud were deserted, and I remained alone with Said, and my servants. The houses now began to swarm with vermin; we no longer slept under the roofs, and it was time to follow the example of the Arabs. I accordingly encamped on the edge of a large pond on the outskirts of Nimroud. Said accompanied me; and Salah, his young wife, a bright-eyed Arab girl, built up his shed, and watched and milked his diminutive flock of sheep and goats. I was surrounded by Arabs, who had either pitched their tents, or, too poor to buy the black goat-hair cloth of which they are made, had erected small huts of reeds and dry grass. When I returned in the evening after the labour of the day, I often sat at the door of my tent, and giving myself up to the full enjoyment of that calm and repose which are imparted to the senses by such scenes as these, I gazed listlessly on the varied groups before me. As the sun went down behind the low hills which separate the river from the desert — even their rocky sides had struggled to emulate the verdant clothing of the plain — its receding rays were gradually withdrawn, like a transparent veil of light, from the landscape. Over the pure, cloudless sky was the glow of the last light. The great mound threw its dark shadow far across the plain. In the distance, and beyond the Zab, Keshaf, another venerable ruin, rose indistinctly into the evening mist. Still more distant, and still more indistinct was a solitary hill overlooking the ancient city of Arbela. The Kurdish mountains, whose snowy summits cherished the dying sunbeams, yet struggled with the twilight. The bleating of sheep and lowing of cattle, at first faint, became louder as the flocks returned from their pastures, and wandered amongst the tents. Girls hurried over the greensward to seek their fathers' cattle, or crouched down to milk those which had returned alone to their well-remembered folds. Some were coming; from the river bearing the replenished pitcher on their heads or shoulders; others, no less graceful in their form, and erect in their carriage, were carrying the heavy load of long grass which they had cut in the meadows. Sometimes a party of horsemen might have been seen in the distance slowly crossing the plain, the tufts of ostrich feathers which topped their long spears showing darkly against the evening sky. They would ride up to my tent, and give me the usual salutation, " Peace be with you, O Bey," or, " Allah Aienak, God help you." Then driving the end of their lances into the ground, they would spring from their mares, and fasten their halters to the still quivering weapons. Seating themselves on the grass, they related deeds of war and plunder, or speculated on the site of the tents of Sofuk, until the moon rose, when they vaulted into their saddles and took the way of the desert. The plain now glittered with innumerable tires. As the night advanced, they vanished one by one until the landscape was wrapped in darkness and in silence, only disturbed by the barking of the Arab dog. Abd-ur-rahman rode to my tent one morning, and offered to take me to a remarkable cutting in the rock, which he described as the work of Nimrod, the Giant. The Arabs call it "Negoub," or, The Hole. A¥e were two hours in reaching the place, as we hunted gazelles and hares by the way. A tunnel, bored through the rock, opens by two low arched outlets, upon the river. It is of considerable length, and is continued for about a mile by a deep channel, also cut out of the rock, but open at the top. I suspected at once that this was an Assyrian work, and, on examining the interior of the tunnel, I discovered a slab covered with cuneiform characters, which had fallen in from a platform, and had been wedged in a crevice of the rock. With much difficulty I succeeded in ascertaining that an inscription was also cut on the back of the tablet. From the darkness of the place, I could scarcely copy even the few characters which had resisted the wear of centuries. Some days after, others who had casually heard of my visit, and conjectured that some Assyrian remains might have been found there, sent a party of workmen to the spot; who, finding the slab, broke it into pieces, in their attempt to displace it. This wanton destruction of the tablet is much to be regretted; as, from the fragment of the inscription I copied, I can perceive that it contained an important, and, to me, new genealogical list of kings. I had intended to remove the stone carefully, and had hoped, by placing it in a proper light, to ascertain accurately the forms of the various characters upon it. This was not the only loss I had to complain of, from the jealousy and competition of rivals. The tunnel of Negoub is undoubtedly a remarkable work, undertaken, as far as I can judge by the fragment of the inscription, during the reign of an Assyrian king of the latter dynasty, who may have raised the tablet to commemorate the completion of the work. Its object is rather uncertain. It may have been cut to lead the waters of the Zab into the surrounding country for irrigation; or it may have been the termination of the great canal, which is still to be traced by a double range of lofty mounds, near the ruins of Nimroud, and which may have united the Tigris with the neighbouring river, and thus fertilised a large tract of land. In either case, the level of the two rivers, as well as the face of the country, must have changed considerably since the period of its construction. At present Negoub is above the Zab, except at the time of the highest flood in the spring, and then water is only found in the mouth of the tunnel; all other parts having been much choked up with rubbish and river deposits.

|

|

|

|

|

1) The former hereditary governors of Mosul. 2) I shall in future always designate this figure, which frequently occurs in the Assyrian bas-reliefs, the King's Vizur or Minister. It has been conjectured that the person represented is a friendly or tributary monarch, but as he often occurs amongst the attendants, aiding the king in his battles, or waiting upon him at the celebration of religious ceremonies, with his hands crossed in front, as is still the fashion in the East with dependants, it appears more probable that he was his adviser or some high officer of the court. 3) Chamber A, plan 3. 4) Entrance to chamber B B. 5) No. 32. chamber B, plan 3. 6) It has been suggested that this is the head of a cock, but it is unquestionably that of a carnivorous bird of the eagle tribe. 7) Entrance of chamber B, plain 3. 8) Ezekiel, xxxi. 3., &c., Zephaniah, ii. 13. and 14. 9) Chamber C. 10) These double titles are very common amongst the Kurds, as Beder Khan Bey, Mir Kur Ullah Bey, &c. The Porte, however, persists in writing the word Khan, " Kan," because it will not recognise In any one else a title which is given by the Turks to the Osmaulee Sultans alone. So the word " Hadji," a Pilgrim, when applied to a Christian is not written the same as when borne by a Musulman, for a religious epithet would be polluted if added to the name of an unbeliever. 11) The Sheeas and some other sects, who scrupulously adhere to the precepts of the Koran and to the Hadith or sacred traditions, make a distinction between those things which may be used or touched by a Musulman after they have been in the hands of a Christian, and those which may not; this distinction depends upon whether they be, according to their doctors, absorbents or non-absorbents. If they are supposed to absorb moisture, they become unclean after contact with an unbeliever.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD