Nineveh and Its Remains

Volume 1

By Austen Henry Layard, ESQ. D.C.L.

Part 1 - Chapter 4

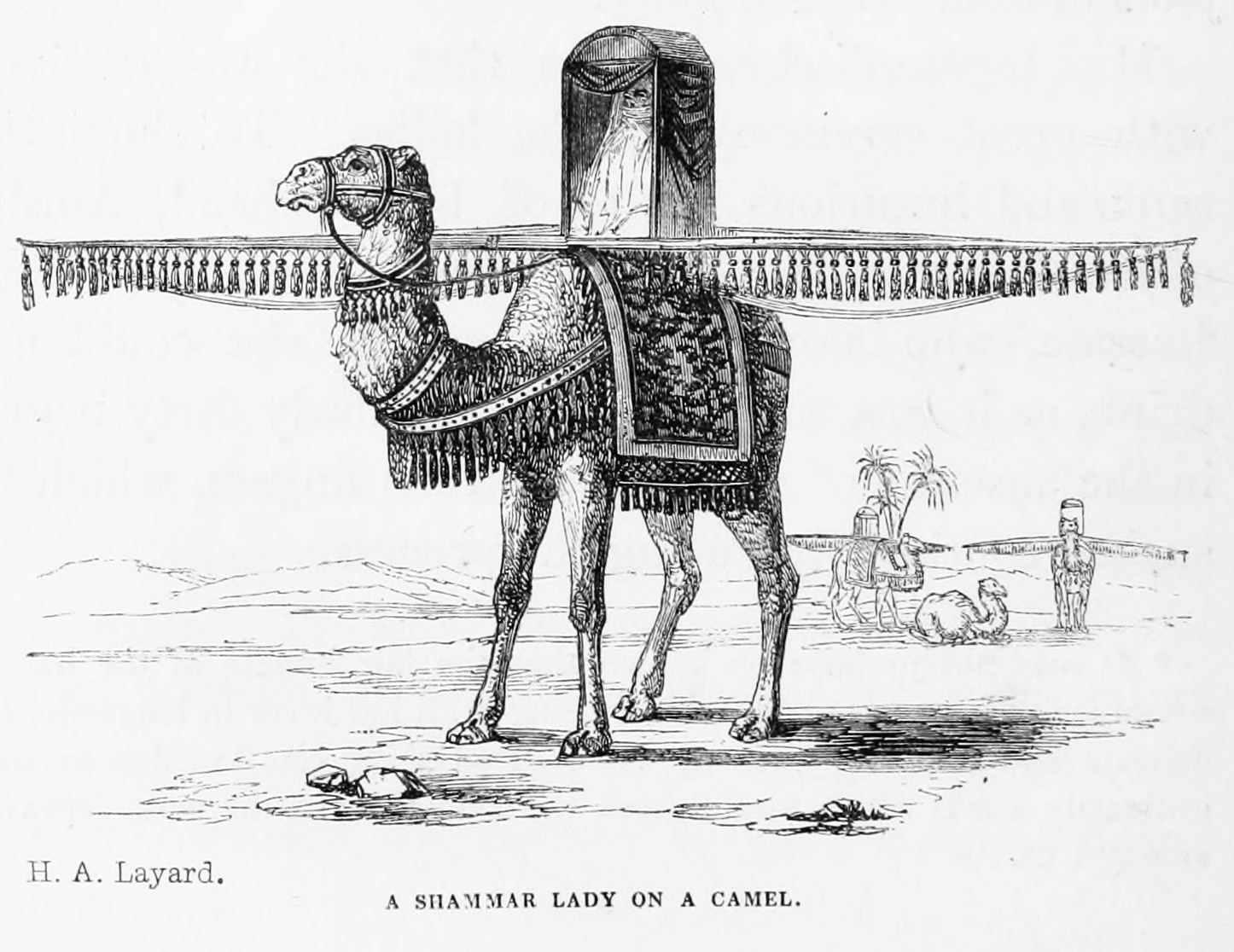

The operations at Nimroud having been completely suspended until I could receive assistance from Constantinople, I thought the time not inopportune to visit Sofuk, the Sheikh of the great Arab tribe of Shammar, which occupies nearly the whole of Mesopotamia. He had lately left the Kabour, and was now encamped near the western bank of the Tigris, below its junction with the Zab, and consequently not far from Nimroud. I had two objects in going to his tents; in the first place I wished to obtain the friendship of the chief of a large tribe of Arabs, who would probably cross the river in the neighbourhood of the excavations during the summer, and might indulge, to my cost, in their plundering propensities; and, at the same time, I was anxious to visit the remarkable ruins of Al Hather, which I had only examined very hastily on my former journey. Mr. Rassam (the Yice-Consul) and his wife, with several native gentlemen of Mosul, Mussulmans and Christians, were induced to accompany me; and, as we issued from the gates of the town, and assembled in the well-peopled burying-ground opposite the Governor's palace, I found myself at the head of a formidable party. Our tents, obtained from the Pasha, and our provisions and necessary furniture, were carried by a string of twelve camels. Mounted above these loads, and on donkeys, was an army of camel-drivers, tent-pitchers, and volunteers ready for all services. There were, moreover, a few irregular horsemen, the Cawasses, the attendants of the Mosul gentlemen, the Mosul gentlemen themselves, and our own servants, all armed to the teeth. Ali Effendi, chief of the Mosul branch of the Omeree, or descendants of Omar, which had furnished several Pashas to the province, was our principal Mussulman friend. He w^as mounted on the Hedban, a well-known white Arab, beautiful in form and pure in blood, but now of great age. Close at his horse's heels followed a confidential servant; who, perched on a pack-saddle, seemed to roll from side to side on two small barrels, the use of which might have been an enigma, had they not emitted a very strong smell of raki. A Christian gentleman was wrapped up in cloaks and furs, and appeared to dread the cold, although the thermometer was at 100. The English lady w^as equipped in riding-habit and hat. The two Englishmen, Mr. Ross and myself, wore a striking mixture of European and oriental raiments. Mosul ladies, in blue veils, their faces concealed by black horse-hair sieves, had been dragged to the top of piles of carpets and cushions, under which groaned their unfortunate mules. Greyhounds in leashes were led by Arabs on foot; whilst others played with strange dogs, who followed the caravan for change of air. The horsemen galloped round and round, now dashing into the centre of the crowd, throwing their horses on their haunches when at full speed, or discharging their guns and pistols into the air. A small flag with British colours was fastened to the top of a spear, and confided to a Cawass. Such was the motley caravan which left Mosul by the Bab el Top, where a crowd of women had assembled to witness the procession. We took the road to the ruins of the monastery of Mar Elias, a place of pilgrimage for the Christians of Mosul, which we passed after an hour's ride. Evening set in before we could reach the desert, and we pitched our tents for the night on a lawn near a deserted village, about nine miles from the town. On the following morning we soon emerged from the low limestone hills; which, broken into a thousand rocky valleys, form a barrier between the Tigris and the plains of Mesopotamia. We now found ourselves in the desert, or rather wilderness; for at this time of the year, nature could not disclose a more varied scene, or a more luxuriant vegetation. We trod on an interminable carpet, figured by flowers of every hue. Nor was water wanting; for the abundant rains had given reservoirs to every hollow, and to every ravine. Their contents, owing to the nature of the soil, were brackish, but not unwholesome. Clusters of black tents were scattered, and flocks of sheep and camels wandered, over the plain. Those of our party who were well mounted urged their horses through the meadows, pursuing the herds of gazelles, or the wild boar, skulking in the long grass. Although such scenes as these may be described, the exhilaration caused by the air of the desert in spring, and the feeling of freedom arising from the contemplation of its boundless expanse, must have been experienced before they can be understood. The stranger, as well as the Arab, feels the intoxication of the senses which they produce. From their effects upon the wandering son of Ishmael, they might well have been included by the Prophet amongst those things forbidden to the true believer. The first object we had in view was to discover the tents of Sofuk. The Sheikh had been lately exposed to demands on the part of the governors of Mosul and Baghdad; and, moreover, an open hostility to his authority had arisen amongst the Shammar tribes. He was consequently keeping out of sight, and seeking the most secluded spots in the desert to pitch his tents. We asked our way of the parties of Arab horsemen, whom we met roving over the plain; but received different answers from each. Some were ignorant; others fancied that our visit might be unacceptable, and endeavoured to deceive us. About mid-day we found ourselves in the midst of extensive herds of camels. They belonged to the Haddedeen. The sonorous whoop of the Arab herdsmen resounded from all sides. A few horsemen were galloping about, driving back the stragglers, and directing the march of the leaders of the herd. Shortly after we came up with some families moving to a new place of encampment, and at their head I recognised my old antiquity hunter, Mormons. He no sooner perceived us than he gave orders to those who followed him, and of whom he was the chief, to pitch the tents. We were now in the Wadi Ghusub, formed by a small salt stream, which forces its sluggish way through a dense mass of reeds and water shrubs, from whence the valley has taken its name. About fifteen tents were soon raised. A sheep was slaughtered in front of the one in which we sat; large wooden bowls of sour milk, and platters of fresh butter were placed before us; fires of camel's dung were lighted; decrepit old women blew up the flames; the men cut the carcase into small pieces, and capacious cauldrons soon sent forth volumes of steam. Mormons tended the sheep of Ali Effendi, our travelling companion, as well as his own.1 The two were soon in discussion, as to the amount of butter and wool produced. Violent altercations arose on the subject of missing beasts. Heavy responsibilities, which the Effendi did not seem inclined to admit, were thrown upon the wolves. Some time elapsed before these vital questions were settled to the satisfaction of both parties; ears having been produced, oaths taken, and witnesses called, with the assistance of wolves and the rot, the diminution in the flocks was fully accounted for. The sheep was now boiled. The Arabs pulled the fragments out of the cauldron and laid them on wooden platters with their fingers. We helped ourselves after the same fashion. The servants succeeded to the dishes, which afterwards passed through the hands of the camel drivers and tent pitchers; and at last, denuded of all apparently edible portions, reached a strong party of expectant Arabs. The condition of the bones by the time they were delivered to a crowd of hungry dogs, assembled on the occasion, may easily be imagined. We resumed our journey in the afternoon, preceded by Mormons, who voluntered to accompany us. As we rode over the plain, we fell in with the Sheikh of the Haddedeen, mounted on a fine mare, and followed by a large concourse of Arabs, driving their beasts of burden loaded with tents and furniture. He offered to conduct us to a branch of the Shammar, whose encampment we could reach before evening. We gladly accepted his offer, and he left his people to ride with us. We had been wandering to and fro in the desert, uncertain as to the course we should pursue. The Sheikh now rode in the direction of the Tigris. Before nightfall we came to a large encampment, and recognised in its chief one Khalaf, an Arab who frequently came to Mosul, and whom Mr. Rassam and myself had met on our previous journey to Al Hather. His tribe, although a branch of the Shammar, usually encamp near the town; and avoid, if possible, the broils which divide their brethren. Strong enough to defend themselves against the attacks of other Arabs, and generally keeping at a sufficient distance from Mosul to be out of reach of the devastating arm of its governors, they have become comparatively wealthy. Their flocks of sheep and camels are numerous, and their Sheikhs boast some of the finest horses and mares in Mesopotamia. Sheikh Khalaf received us with hospitality; sheep were immediately slaughtered, and we dismounted at his tent. Even his wives, amongst whom was a remarkably pretty Arab girl, came to us to gratify their curiosity by a minute examination of the Frank lady. As the intimacy, which began to spring up, was somewhat inconvenient, we directed our tents to be pitched at a distance from the encampment, by the side of a small stream. It was one of those calm and pleasant evenings, which in spring make a paradise of the desert. The breeze, bland and perfumed by the odour of flowers, came calmly over the plain. As the sun went down, countless camels and sheep wandered to the tents, and the melancholy call of the herdsmen rose above the bleating of the flocks. The Arabs led their prancing mares to the water: the colts, as they followed, played and rolled on the grass. I spread my carpet at a distance from the group, to enjoy uninterrupted the varied scene. Rassam, now in his element, collected around him a knot of wondering Arabs, unscrewed telescopes, exhibited various ingenious contrivances, and described the wonders of Europe, interrupted by the exclamations of incredulous surprise, which his marvellous stories elicited from the hearers. Ali Effendi and his Mussulman friends, who preferred other pleasures and more definite excitement, hid themselves in the high rushes, and handed round a small silver bowl containing fragrant ruby-coloured spirits, which might have rejoiced even the heart of Hafiz. The camel-drivers and servants hurried over the lawn, tending their animals or preparing for the evening meal. We had now reached the pasture-grounds of the Shammar, and Sheikh Khalaf declared that Sofuk's tents could not be far distant. A few days before they had been pitched almost amongst the ruins of Al Hather; but he had since left them, and it was not known where he had encamped. We started early in the morning, and took the direction pointed out by Khalaf. Our view was bounded to the east by a rising ground. When we reached its summit, we looked down upon a plain, which appeared to swarm with moving objects. We had come upon the main body of the Shammar. It would be difficult to describe the appearance of a large tribe, like that we now met, when migrating to new pastures. The scene caused in me feelings of melancholy, for it recalled many hours, perhaps unprofitably, though certainly happily spent; and many friends, some who now sighed in captivity for the joyous freedom which those wandering hordes enjoyed; others who had perished in its defence. We soon found ourselves in the midst of wide-spreading flocks of sheep and camels. As far as the eye could reach, to the right, to the left, and in front, still the same moving crowd. Long lines of asses and bullocks laden with black tents, huge cauldrons and variegated carpets; aged women and men, no longer able to walk, tied on the heap of domestic furniture; infants crammed into saddle-bags, their tiny heads thrust through the narrow opening, balanced on the animal's back by kids or lambs tied on the opposite side; young girls clothed only in the close-fitting Arab shirt, which displayed rather than concealed their graceful forms; mothers with their children on their shoulders; boys driving flocks of lambs; horsemen armed with their long tufted spears, scouring the plain on their fleet mares; riders urging their dromedaries with their short hooked sticks, and leading their high-bred steeds by the halter; colts galloping amongst the throng; highborn ladies seated in the centre of huge wings, which extend like those of a butterfly from each side of the camel's hump, and are no less gaudy and variegated. Such was the motley crowd through which we had to wend our way for several hours. Our appearance created a lively sensation; the women checked our horses; the horsemen assembled round us, and rode by our side; the children yelled and ran after the Franks. It was mid-day before we found a small party that had stopped, and were pitching their tents. A young chesnut mare belonging to the Sheikh, was one of the most beautiful creatures I ever beheld. As she struggled to free herself from the spear to which she was tied, she showed the lightness and elegance of the gazelle. Her limbs were in perfect symmetry; her ears long, slender and transparent; her nostrils high, dilated and deep red; her neck gracefully arched, and her main and tail of the texture of silk. We all involuntarily stopped to gaze at her. "Say Masha-AUah," exclaimed the owner, who, seeing not without pride, that I admired her, feared the effect of an evil eye. "That I will," answered I, " and with pleasure; for, Arab, you possess the jewel of the tribe." He brought us a bowl of camel's milk, and directed us to the tents of Sofuk. We had still two hours' ride before us, and when we reached the encampment of the Shammar Sheikh, our horses, as well as ourselves, were exhausted by the heat of the sun, and the length of the day's journey- The tents were pitched on a broad lawn in a deep ravine; they were scattered in every direction, and amongst them rose the white pavilions of the Turkish irregular cavalry. Ferhan, the son of Sofuk, and a party of horsemen, rode out to meet us as we approached, and led us to the tent of the chief, distinguished from the rest by its size, and the spears which were driven into the ground at its entrance. Sofuk advanced to receive us; he was followed by about three hundred Arabs, including many of the principal Sheikhs of the tribe. In person he was short and corpulent, more like an Osmanli than an Arab; but his eye was bright and intelligent, his features regular, well formed and expressive. His dress differed but in the quality of the materials from that of his followers. A thick kerchief, striped with red, yellow, and blue, and fringed with long platted cords, was thrown over his head, and fell down his shoulders. It was held in its place, above the brow, by a band of spun camel's wool, tied at intervals by silken threads of many colours. A long white shirt, descending to the ankles, and a black and white cloak over it, completed his attire. He led Rassam and myself to the top of the tent, where we seated ourselves on well-worn carpets. When all the party had found places, the words of welcome, which had been exchanged before we dismounted, were repeated. "Peace be with you, O Bey! upon my head you are welcome; my house is your house," exclaimed the Sheikh, addressing the stranger nearest to him. " Peace be with you, Sofuk! may God protect you! " was the answer, and similar compliments were made to every guest and by every person present. Whilst this ceremony, which took nearly half an hour, was going on, I had leisure to examine those who had assembled to meet us. Nearest to me was Ferhan, the Sheikh's son, a young man of handsome appearance and intelligent countenance, although the expression was neither agreeable nor attractive. His dress resembled that of his father; but from beneath the handkerchief thrown over his head hung his long black tresses platted into many tails. His teeth were white as ivory, like those of most Arabs. Beyond him sat a crowd of men of the most ferocious and forbidding exterior — warriors who had passed their lives in war and rapine, looking upon those who did not belong to their tribe as natural enemies, and preferring their wild freedom to all the riches of the earth. Mrs. Rassam had been ushered into this crowded assembly, and the scrutinising glance with which she was examined from head to foot, by all present, was not agreeable. We requested that she might be taken to the tent of the women. Sofuk called two black slaves, who led her to the harem, scarcely a stone's-throw distant. The compliments having been at length finished, we conversed upon general topics. Coffee, highly drugged with odoriferous roots found in the desert, and with spices, a mixture for which Sofuk has long been celebrated, was handed round before we retired to our own tents. Sofuk's name was so well known in the desert, and he so long played a conspicuous part in the politics of Mesopotamia, that a few words on his history may not be uninteresting. He was descended from the Sheikhs, who brought the tribe from Nedjd. At the commencement of his career he had shared the chiefship with his uncle, after whose death he became the great Sheikh of the Shammar. From an early period he had been troublesome to the Turkish governors, of the provinces on the Tigris and Euphrates; but gained the applause and confidence of the Porte by a spirited attack which he made upon the camp of Mohammed Ali Mirza, son of Fetli Ali Shah, and governor of Kirmanshah, when that prince was marching upon Baghdad and Mosul. After this exploit, to which was mainly attributed the safety of the Turkish cities, Sofuk was invested as Sheikh of the Shammar. At times, however, when he had to complain of ill-treatment from the Pasha of Baghdad, or could not control those under him, his tribes were accustomed to indulge their love of plunder, to sack villages and pillage caravans. He thus became formidable to the Turks, and was known as the Kino; of the Desert. When Mehemet Reshid Pasha led his successful expedition into Kurdistan and Mesopotamia, Sofuk was amongst the chiefs whose power he sought to destroy. He knew that it would be useless to attempt it by force, and he consequently invited the Sheikh to his camp on the pretence of investing him with the customary robe of honour. He was seized and sent a prisoner to Constantinople. Here he remained some months, until deceived by his promises, the Porte permitted him to return to his tribes. From that time his Arabs had generally been engaged in plunder, and all efforts to subdue them had failed. They had been the terror of the Pashalies of Mosul and Baghdad, and had even carried their depredations to the east of the Tigris. However, Nejris, the son of Sofuk's uncle, had appeared as his rival, and many branches of the Shammar had declared for the new Sheikh. This led to dissensions in the tribe; and, at the time of our visit, Sofuk, who had forfeited his popularity by many acts of treachery, was almost deserted by the Arabs. In this dilemma he had applied to the Pasha of Mosul, and had promised to serve the Porte and to repress the depredations of the tribes, if he were assisted in re-establishing his authority. This state of things accounted for the presence of the white tents of the Hytas in the midst of the encampment. His intercourse with the Turkish authorities, who must be conciliated by adequate presents before assistance can be expected from them; and the famine, which for the last two years had prevailed in the countries surrounding the desert, were not favourable to the domestic prosperity of Sofuk. The wealth and display, for which he was once renowned amongst the Arabs, had disappeared. A few months before, he had even sent to Mosul the silver ankle-rings of his favourite wife — the last resource — to be exchanged for corn. The furred cloaks, and embroidered robe, which he once wore, had not been replaced. The only carpet in his tent was the rag on which sat his principal guests; the rest squatted on the grass, or on the bare ground. He led the life of a pure Bedouin, from the commonest of whom he was only distinguished by the extent of his female establishment — always a weak point with the Sheikh. But even in his days of greatest prosperity, the meanest Arab looked upon him as his equal, addressed him as " Sofuk," and seated himself unbidden in his presence. The system of patriarchal government, faithfully described by Burckhardt, still exists, as it has done for 4000 years, in the desert. Although the Arabs for convenience recognise one man as their chief; yet any unpopular or oppressive act on his part at once dissolves their allegiance; and they seek, in another, a more just and trustworthy leader. Submitting, for a time, to contributions demanded by the Sheikh, if they believe them to be necessary for the honour and security of the tribe, they consider themselves the sole judges of that necessity. The chief is consequently always unwilling to risk his authority by asking for money, or horses, from those under him. He can only govern as long as he has the majority in his favour. He moves his tent; and others, who are not of his own family, follow him if they think proper. If his ascendancy is great, and he can depend upon his majority, he may commit acts of bloodshed and oppression, becoming an arbitrary ruler; but such things are not forgotten by the Arabs, or seldom in the end go unpunished. Of this Sofuk himself was, as it will be seen hereafter, an example. The usual Arab meal was brought to us soon after our arrival — large wooden bowls and platters tilled with boiled fragments of mutton swimming in melted butter, and sour milk. When our breakfast was removed, the chief of the Hytas called upon us. I had known him at Mosul; he was the commander of the irregular troops stationed at Selamiyah, and had been the instrument of the late Pasha in my first troubles, as he now good-humouredly avowed. He was called Ibraham Agha, Goorgi Oglu, or the son of the Georgian, from his Christian origin. In his person he was short; his features wore regular, and his eyes bright; his compressed brow, and a sneer, which continually curled his lip, well marked the character of the man. In appearance he was the type of his profession; his loose jacket, tight under vest, and capacious shtilwars, were covered with a mass of gold embroidery; the shawls round his head and waist were of the richest texture and gayest colours; the arms in his girdle of the costliest description, and his horses and mares were renowned. His daring and courage had made him the favourite of Mohammed Pasha; and he was chiefly instrumental in reducing to obedience the turbulent inhabitants of Mosul and Kurdistan, during the struggle between that governor and the hereditary chiefs of the province. One of his exploits deserves notice. Some years ago there lived in the Island of Zakko, formed by the river Khabour, and in a castle of considerable strength, a Kurdish Bey of great power and influence. Whilst his resistance to the authority of the Porte called for the interference of Mohammed Pasha, the reports of his wealth were no mean incentives to an expedition against him. All attempts, however, to seize him and reduce his castle had failed. At the time of my first visit to Mesopotamia he still lived as an independent chief, and I enjoyed for a night his hospitality. He was one of the last in this part of Kurdistan who kept up the ancient customs of the feudal chieftains. His spacious hall, hung around with arms of all kinds, with the spreading antlers of the stag and the long knotted horns of the ibex, was filled ever}^ evening with guests and strangers. After sunset the floor was covered with dishes overflowing with various messes. The Bey sat on cushions at the top of the hall, and by him were placed the most favoured guests. After dinner he retired to his harem; every one slept where it was most convenient to himself, and rising at daybreak, went his way without questions from his host. The days of the chief were spent in war and plunder, and half the country had claims of blood against him. " Will no one deliver me from that Kurdish dog?" exclaimed Mohammed Pasha one day in his salamlik, after an ineffectual attempt to reduce Zakko; " By God and his Prophet, the richest cloak of honour shall be for him who brings me his head." Ibrahim Agha, who was standing amongst the Pasha's courtiers, heard the offer and left the room. Assembling a few of his bravest followers, he took the road to the mountains. Concealing all his men, but six or eight, in the gardens outside the small town of Zakko, he entered after nightfall the castle of the Kurdish chief. He was received as a guest, and the customary dishes of meat were placed before him. After he had eaten he rose from his seat, and advancing towards his host, fired his long pistol within a few feet of the breast of the Bey, and drawing his sabre, severed the head from the body. The Kurds, amazed at this unparalleled audacity, offered no resistance. A signal from the roof was answered by the men outside; the innermost recesses of the castle were rifled, and the Georgian returned to Mosul with the head and wealth of the Kurdish chieftain. The Castle of Zakko was suffered to fall into decay; Turkish rule succeeded to Kurdish independence; and a few starving Jews are now alone found amongst the heap of ruins. But this is not the last deed of daring of Ibrahim Agha: Sofuk himself, now his host, was destined likewise to become his victim. After the Hyta-bashi had retired, Sofuk came to our tents and remained with us the greater part of the day. He was dejected and sad. He bewailed his poverty, inveighed against the Turks, to whom he attributed his ruin, and confessed, with tears, that his tribe was fast deserting him. Whilst conversing on these subjects, two Sheikhs rode into the encampment, and hearing that the chief was with us, they fastened their his-h-bred mares at the door of our tent and seated themselves on our carpets. They had been amongst the tribes to ascertain the feeling of the Shammar towards Sofuk, of whom they were the devoted adherents. One was a man of forty, blackened by long exposure to the desert sun, and of a savage and sanguinary countenance. His companion was a youth, his features were so delicate and feminine, and his eyes so bright that he might have been taken for a woman; the deception would not have been lessened by a profusion of black hair which fell, platted into numerous tresses, on his breast and shoulders. An animated discussion took place as to the desertion of the Nejm, a large branch of the Shammar tribe. The young man's enthusiasm and devotedness knew no bounds. He threw himself upon Sofak, and clinging to his neck covered his cheek and beard with kisses. When the chief had disengaged himself, his follower seized the edge of his garment, and sobbed violently as he held it to his lips. "I entreat thee, Sofuk! " he exclaimed, " say but the word; by thine eyes, by thy beard, by the Prophet, order it, and this sword shall find the heart of Nejris, whether he escape into the farthest corner of the desert, or be surrounded by all the warriors of the tribe." But it was too late, and Sofuk saw that his influence in the tribe was fast declining. Mrs. Rassam, having returned from her visit to the ladies, described her reception. I must endeavour to convey to the reader some idea of the domestic establishment of a great Arab Sheikh. Sofuk, at the time of our visit, was the husband of three wives, v/ho were considered to have special claims to his affection and his constant protection; for it was one of Sofuk's weaknesses, arising either from a desire to impress the Arabs with a notion of his greatness and power, or from a partiality to the first stage of married life, to take a new partner nearly every month; and at the end of that period to divorce her, and marry her to one of his attendants. The happy man thus lived in a continual honeymoon. Of the three ladies now forming his harem, the chief was Amsha, a lady celebrated in the song of every Arab of the desert, for her beauty and noble blood. She was daughter of Hassan, Sheikh of the Tai, a tribe tracing its origin from the remotest antiquity, and one of whose chiefs, Hatem, her ancestor, is a hero of Eastern romance. Sofuk had carried her away by force from her father; but had always treated her with great respect. From her rank and beauty she had earned the title of " Queen of the Desert." Her form, traceable through the thin shirt which she wore like other Arab women, was well proportioned and graceful. She was tall in stature, and fair in complexion. Her features were regular, and her eyes dark and brilliant. She had undoubtedly claims to more than ordinary beauty; to the Arabs she was perfection, for all the resources of their art had been exhausted to complete what nature had begun. Her lips were dyed deep blue, her eyelids were continued in indigo until they united over the nose, her cheeks and forehead were spotted with beauty-marks, her eyelashes darkened by kohl; and on her legs and bosom could be seen the tattooed ends of flowers and fanciful ornaments, which were carried in festoons and network over her whole body. Hanging from each ear, and reaching to her waist, was an enormous earring of gold, terminating in a tablet of the same material, carved and ornamented with four turquoises. Her nose was also adorned with a prodigious gold ring, set with jewels, of such ample dimensions that it covered the mouth, and was to be removed when the lady ate. Ponderous rows of strung beads, Assyrian cylinders, fragments of coral, agates, and parti-coloured stones, hung from her neck; loose silver rings encircled her wrists and ankles, making a loud jingling as she walked. Over her blue shirt was thrown, when she issued from her tent, a coarse striped cloak, and a common black handkerchief was tied round her head. Her ménage combined, if the old song be true, the domestic and the queenly, and was carried on with a nice appreciation of economy. The immense sheet of black goat-hair canvass, which formed the tent, was supported by twelve or fourteen stout poles, and was completely open on one side. Being entirely set apart for the women it had no partitions, as in the tent of the common Arab, who is obliged to reserve a corner for the reception of his guests. Between the centre poles were placed, upright and close to one another, large camel or goat-hair sacks, filled with rice, corn, barley, coffee, and other household stuff; their mouths being, of course, upwards. Upon them were spread carpets and cushions, on which Amsha reclined. Around her, squatted on the ground, were some fifty handmaidens, tending the wide cauldron, baking bread on the iron plate heated over the ashes, or shaking between them the skin suspended between three stakes, and filled with milk, to be thus churned into butter. It is the privilege of the head wife to prepare in her tent the dinners of the Sheikh's guests. The fires, lighted on all sides, sent forth a cloud of smoke, which hung heavily under the folds of the tent, and would have long before dimmed any eyes less bright than those of Amsha. As supplies were asked for by the women she lifted the corner of her carpet, untied the mouths of the sacks, and distributed their contents. Everything passed through her hands. To show her authority and rank she poured continually upon her attendants a torrent of abuse, and honoured them with epithets of which I may be excused attempting to give a translation; her vocabulary equalling, if not exceeding, in richness that of the highly educated lady of the city.2 The combination of the domestic and authoritative was thus complete. Her children, three naked little urchins, black with sun and mud, and adorned with a long tail hanging from the crown of their heads, rolled in the ashes or on the grass. Amsha, as I have observed, shared the affections, though not the tent of Sofuk — for each establishment had a tent of its own — with two other ladies; Atouia, an Arab not much inferior to her rival in personal appearance; and Ferrah, originally a Yezidi slave, who had no pretensions to beauty. Amsha, however, always maintained her sway, and the others could not sit, without her leave, in her presence. To her alone were confided the keys of the larder — supposing Sofuk to have had either keys or larder — and there was no appeal from her authority on all subjects of domestic economy. Mrs. Rassam informed me that she was received with great ceremony by the ladies. To show the rank and luxurious habits of her husband, Amsha offered her guest a glass of "eau sucrée," which Mrs. Rassam, who is over-nice, assured me she could not drink, as it was mixed by a particularly dirty negro, in the absence of a spoon, with his fingers, which he sucked continually during the process. When the tribe is changing its pastures, the ladies of the Sheikhs are placed on the backs of dromedaries in the centre of the most extraordinary contrivance that man's ingenuity, and a love of the picturesque, could have invented. A light framework, varying from sixteen to twenty feet in length, stretches across the hump of the camel. It is brought to a point at each end, and the outer rods are joined by distended parchment; two pouches of gigantic pelicans seem to spring from the sides of the animal. In the centre, and over the hump, rises a small pavilion, under which is seated the lady. The whole machine, as well as the neck and body of the camel, is ornamented with tassels and fringes of worsted of every hue, and with strings of glass beads and shells. It sways from side to side as the beast labours under the unwieldy burthen; looking, as it appears above the horizon, like some stupendous butterfly skimming slowly over the plain.

In the evening Arasha and Ferrah returned Mrs. Rassam's visit; Sofuk having, however, first obtained a distinct promise that they were not to be received in a tent where gentlemen were to be admitted. They were very inquisitive, and their indiscreet cariosity could with difficulty be satisfied. I may mention that Sofuk was the owner of a mare of matchless beauty, called, as if the property of the tribe, the Shammeriyah. Her dam, who died about ten years ago, was the celebrated Ivubleh, whose renown extended from the sources of the Khabour to the end of the Arabian promontory, and the day of whose death is the epoch from which the Arabs of Mesopotamia now date the events concerning their tribe. Mohammed Emin, Sheikh of the Jebour, assured me that he had seen Sofuk ride down the wild ass of the Sinjar on her back, and the most marvellous stories are current in the desert as to her fleetness and powers of endurance. Sofuk esteemed her and her daughter above all the riches of the tribe; for her he would have forfeited all his wealth, and even Amsha herself. Owing to the visit of the irregular troops, the best horses of the Sheikh and his followers were concealed in a secluded ravine at some distance from the tents. Al Hather was about eighteen miles from Sofuk's encampment. He gave us two well-known horsemen to accompany us to the ruins. Their names were Dathan and Abiram. The former was a black slave, to whom the Sheikh had given his liberty and a wife — two things, it may be observed, which are in the desert perfectly consistent. He was the most faithful and brave of all the adherents of Sofuk, and the fame of his exploits had spread through the tribes of Arabia. As we rode along, I endeavoured to obtain from him some information concerning his people, but he would only speak on one subject. "Ya Bej,"3 said he, " the Arab only thinks of two things, war and love: war, Ya Bej, every one understands; let us, therefore, talk of love;" and he dwelt upon the beauties of Arab maidens in glowing language, and on the rich reward they offered to him who has distinguished himself in the foray or the light. He then told me how a lover first loved, and how he made his love known. An Arab's affections are quickly bestowed upon any girl that may have struck his fancy as she passed him, when bearing water from the springs, or when moving to fresh pastures. Nothing can equal the suddenness of his first attachment, but its ardour. He is ready to die for her, and gives himself up to desperate feats, or to deep melancholy. The maiden, or the lady of his love, is ignorant of the sentiment she has unconsciously inspired. The lover therefore seeks to acquaint her with his passion. He speaks to a distant relation, or to a member of the tribe who has access to the harem of the tent which she occupies; and after securing his secrecy by an oath, he confesses his love, and entreats his confidant to arrange an interview. If the person addressed consents to talk to the woman, he goes to her when she is alone, and gathering a flower or a blade of grass, lie says to her, "Swear by him who made this flower and us also, that you will not reveal to any one that which I am about to unfold to you." If she be not disposed to encourage the addresses of any lover, or if in other cases she be virtuous, she refuses and goes her way, but will never disclose what has passed; otherwise she answers, " I swear by him who made the leaf you now hold and us," and the man settles a place and time of meeting. Oaths taken under these circumstances are seldom, if ever, broken. The Shammar women are not celebrated for their chastity. Some time after our visit to Sofuk, Mohammed Emin, Sheikh of the Jebour, was a guest at his tents. Some altercation arising between him and Ferhan, he called the son of the chief " a liar." " What manner of unclean fellow art thou," exclaimed Sofuk, " to address thus a Sheikh of the Shammar? Dost thou not know that there is not a village in the pashalic of Mosul in which the Arab name is not dishonoured by a woman of the Jebour?" "That may be," replied the indignant chief; " but canst thou point out, Sofuk, a man of the Nejm who can say that his father is not of the Jebour?" This reproach, which the fame of the large branch of the Shammar to which he alluded warranted to a certain extent, so provoked Sofuk, that he sprang upon his feet, and, drawing his sword, would have murdered his guest had not those who sat in the tent interposed. The system of marriages, and the neglect with which women are treated, cannot but be productive of bad results. If an Arab suspects the fidelity of his wife, and obtains such proof as is convincing to him, he may kill her on the spot; but he generally prefers concealing his dishonour from the tribe, as an exposure would be looked upon as bringing shame upon himself. Sometimes he merely divorces her, which can be done by thrice repeating a certain formula. The woman has most to fear from her own relations, who generally put her to death if she has given a bad name, as they term it, to the family. As we rode to Al Hather, we passed large bodies of the Shammar moving with their tents, flocks, and families. On all sides appeared the huge expanding wings of the camel, such as I have described. Dathan was known to all. As the horsemen approached, they dismounted and embraced him, kissing him, as is customary, on both cheeks, and holding him by the hand until many compliments had been exchanged. A dark thunder-cloud rose behind the time-worn ruins of Al Hather as we approached them. The sun, still throwing its rays upon the walls and palace, lighted up the yellow stones until they shined like gold.4 Mr. Ross and myself, accompanied by an Arab, urged our horses onwards, that we might escape the coming storm; but it burst upon us in its fury ere we reached the palace. The lightning played through the vast buildings, the thunder re-echoed through its deserted halls, and the hail compelled us to rein up our horses, and turn our backs to the tempest. It was a fit moment to enter such ruins as these. They rose in solitary grandeur in the midst of a desert, "in media solitudine posita?," as they stood fifteen centuries before, when described by the Roman historian.5 On my previous visit, the first view I obtained of Al Hather Avas perhaps no less striking. We had been wandering for three days in the wilderness without seeing one human habitation. On the fourth morning a thick mist hung over the place. We had given up the search when the vapours were drawn up like a curtain, and we saw the ruins before us. At that time within the walls were the tents of some Shammar Arabs, but now as we crossed the confused heaps of fragments, forming a circle round the city, we saw that the place was tenantless. Flocks on a neighbouring rising ground showed, however, that Arabs were not distant. We pitched our tents in the great court-yard, in front of the palace, and near the entrance to the inner inclosure. During the three days we remained amongst the ruins I had ample time to take accurate measurements, and to make plans of the various buildings still partly standing within the walls. As Al Hather has already been described by others, and as the information I was able to collect has been placed before the public6, I need not detain the reader with a detailed account of the place. Suffice it to mention, that the walls of the city, flanked by numerous towers, form almost a complete circle, in the centre of which rises the palace, an edifice of great magnificence, solidly constructed of squared stones, and elaborately sculptured with figures and ornaments. It dates probably from the reign of one of the Sassanian Kings of Persia, certainly not prior to the Arsacian dynasty, although the city itself was, I have little doubt, founded at a very early period. The marks upon all the stones, which appear to be either a builder's sign or to have reference to some religious observance, are found in most of the buildings of Sassanian origin in Persia, Babylonia, and Susiana.7 With the exception of occasional alarms in the night, caused by thieves attempting to steal the horses, we were not disturbed during our visit. The Arabs from the tents in the neighbourhood brought us milk, butter, and sheep. We drank the water of the Thathar, which is, however, rather salt; and our servants and camel-drivers filled during the day many baskets with truffles. On our return we crossed the desert, reaching Wadi Ghusub the first night, and Mosul on the following morning. Dathan and Abiram, who had both distinguished themselves in recent foraging parties, and had consequently accounts to settle with the respectable merchants of the place, the balance being very much against them, could not be prevailed upon to enter the town, where they were generally known. We had provided ourselves with two or three dresses of Damascus silk, and we invested our guides as a mark of satisfaction for their services. Dathan grinned a melancholy smile as he received his reward. "Ya Bej," he exclaimed, as he turned his mare towards the desert; " may God give you peace! Wallah, your camels shall be as the camels of the Shammar. Be they laden with gold, they shall pass through our tents, and our people shall not touch them." A year after our visit the career of Sofuk was brought to its close. The last days of his life may serve to illustrate the manners of the country, and the policy of those who are its owners. I have mentioned that Xejris, Sofuk's rival, had obtained the support of nearly the whole tribe of Shammar. In a month Sofuk found himself nearly alone. His relations and immediate adherents, amongst whom were Dathan and Abiram, still pitched their tents with him, but he feared the attacks of his enemies, and retreated for safety into the territory of Beder Khan Bey, to the East of the Tigris, near Jezirah. He sent his son Ferhan with a few presents, and with promises of more substantial gifts in case of success, to claim the countenance and support of Nejib Pasha of Baghdad, under whose authority the Shammar are supposed to be. The Pasha honoured the young Sheikh with his favour, and invested him as chief of the tribe, to the exclusion of Sofuk, whom he knew to be unpopular; but who still, it was understood, was to govern as the real head of the Shammar. He also promised to send a strong military force to the assistance of Ferhan, to enable him to enforce obedience amongst the Arabs. The measures taken by Nejib Pasha had the effect of bringing back a part of the tribe to Sofuk, who now proposed to Nejris, that they should meet at his tents, forget their differences, and share equally the Sheikhship of the Shammar. Nejris would not accept the invitation; he feared the treachery of a man, who had already forfeited his good name as an Arab. Sofuk prevailed upon his son to visit his rival. He hoped through the means of the young chief, who was less unpopular and more trusted than himself, to induce Nejris to accept the terms he had offered, and to come to his encampment. Ferhan refused, and was only persuaded to undertake the mission after his father had pledged himself, by a solemn oath, to respect the laws of hospitality. He rode to the tents of Nejris, who received him with affection, but refused to trust himself in the power of Sofuk, until Ferhan had given his own word that no harm should befall him. " I would not have gone," said he, " to the tents of Sofuk, had he sworn a thousand oaths; but to show you, Ferhan, that I have confidence in your word, I will ride with you alone; " and he mounted his mare, and, unaccompanied by any of his attendants, followed Ferhan to the encampment of his father. His reception showed him at once that he had been betrayed. Sofuk sat in gloomy silence, surrounded by several of the most desperate of his tribe. He rose not to receive his guest, but beckoned him to a place by his side. Ferhan trembled as he looked on the face of his father; but Nejris undaunted advanced into the circle, and seated himself where he had been bidden. Sofuk at once upbraided him as a rebel to his authority, and sought the excuse of a quarrel. As Nejris answered boldly, the occasion was not long wanting. Sofuk sprang to his feet, and drawing his sword threw himself upon his rival. In vain Ferhan appealed to his father's honour, to the laws of hospitality, so sacred to the Arab; in vain he entreated him not to disgrace his son by shedding the blood of one whom he had brought to his tents. Nejris sought protection of Hajar, the uncle of Sofuk, and clung to his garments; but he was one of the most treacherous and bloodthirsty of the Shammar. Upon this man's knee was the head of the unfortunate Sheikh held down, whilst Sofuk slew^ him as he would have slain a sheep. The rage of the murderer was now turned against his son, who stood at the entrance of the tent tearing his garments, and calling down curses upon the head of his father. The reeking sword would have been dipped in his blood, had not those who were present interfered. The Shammar were amazed and disgusted by this act of perjury and treachery. The hospitality of an Arab tent had been violated, and disgrace had been brought upon the tribe. A deed so barbarous and so perfidious had been unknown. They withdrew a second time from Sofuk, and placed themselves under a new leader, a relation of the murdered Sheikh. Sofuk again appealed to Nejib Pasha, justifying his treachery by the dissensions which would have divided the tribe, and would have led to constant disorders in Mesopotamia had there still been rival candidates for the Sheikhship. Nejib pretended to be satisfied, and agreed to send out a party of irregular troops to assist Sofuk in enforcing his authority throughout the desert. The commander of the troops sent by Nejib was Ibrahim Agha, the son of the Georgian, whom we met on our journey into the desert. Sofuk received him with joy, and immediately marched against the tribe; but he himself was the enemy against whom the Agha was sent. He had scarcely left his tent, when he found that he had fallen into a snare which he had more than once set for others. In a few hours after, his head was in the palace of the Pasha of Baghdad. Such was the end of one whose name will long be remembered in the wilds of Arabia; who, from his power and wealth, enjoyed the title of "the King of the Desert," and led the great tribe of Shammar from the banks of the Khabour to the ruins of Babylon. The tale of the Arab will turn for many years to come on the exploits and magnificence of Sofuk.

|

|

|

|

|

1) It is customary for the inhabitants of Mosul possessing flocks to confide them to the Haddedeen Arabs, who take them into the desert during the winter and spring, and pasture them in the low hills to the east of the town during the summer and autumn. The produce of the sheep, the butter and wool, is divided between the owner and the Arab in charge of them; the sour milk, curds, &c., are left to the latter. In case of death the Arab brings the ears, and takes an oath that they belong to the missing animal. 2) It may not perhaps be known that the fair inmate of the harem, whom we picture to ourselves conversing with her lover in language, too delicate and refined to be expressed by anything else but flowers, uses ordinarily words which would shock the ears of even the most depraved amongst us. 3) "Ya Bej," O my Lord; he so prefaced every sentence. The Shammar Arabs pronounce the word Beg, which the Constantinopolitans soften into Bey, Bej. 4) The rich golden tint of the limestone, of which the great monuments of Syria are built, is known to every traveller in that country. The ruins of Al Hather have the same bright colour; they look as if they had been steeped in the sunbeams. 5) Ammianus Marcellinus, lib. 25. cap. 8. 6) Sec Dr. Ross's Memoir in the Geographical Society's Journal, and Dr. Ainsworth's Travels. A memoir on the subject, accompanied by plans, &c., was read before the Institute of British Architects, and partly printed in a number of the Builder. 7) Many of these marks are given in Mr. Ainsworth's Memoir in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society. They are not letters of any one particular alphabet, but they are signs of all kinds. I discovered similar marks at Bisutun, Isphahan, Shuster, and other places in Persia where Sassanian buildings appear to have existed.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD