THE POLITICAL

CAMPAIGN OF 1864.

THE

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION.--THE CLEVELAND CONVENTION.--THE CONVENTION AT BALTIMORE.--MR. LINCOLN'S RENOMINATION AND ACCEPTANCE.--POPULAR FEELING DURING THE SUMMER.--THE ARGUELLES

CASE.--THE FORGED PROCLAMATION.--THE NIAGARA FALLS CONFERENCE.

--THE CHICAGO CONVENTION.--PROGRESS AND RESULT OF THE CAMPAIGN.--POPULAR JOY AT THE RESULT.

THE American people were approaching another test of

their capacity for self-government, in some respects more

trying than any they had yet encountered. As the spring

of 1864 was passing away, the official term of President

Lincoln drew towards its close, and the people were required to choose his successor. At all times and under

the most favorable circumstances, the election of a President is attended with a degree of excitement, which some

of the wisest theorists have pronounced inconsistent with

the permanent harmony and safety of a republican form

of government. But that such an election should become

necessary in the midst of a civil war, which wrapped the

whole country in its flames and aroused such intense and

deadly passions in the public heart, was felt to be foremost among the calamities which had menaced the land.

The two great rebel armies still held the field. The

power of their government was still unbroken. All our

attempts to capture their capital had proved abortive.

The public debt was steadily and rapidly increasing.

Under the resistless pressure of military necessity, the Government, availing itself of the permissions of the Constitution, had suspended the great safeguard of civil freedom,

and dealt with individuals whom it deemed dangerous

to the public safety with as absolute and relentless

severity as the most absolute monarchies of Europe had

ever shown. Taxes were increasing; new drafts of men to fill the ranks

of new armies were impending; the Democratic party, from the very beginning hostile to the war

and largely imbued with devotion to the principle of

State Sovereignty on which the rebellion rested, and

with toleration for slavery out of which it grew, was

watching eagerly for every means of arousing popular

hatred against the Government, that they might secure its

transfer to their own hands; and the losses, the agonies,

the desolations of the war were beginning, apparently, to

make themselves felt injuriously upon the spirit, the endurance, the hopeful resolution of the people throughout

the loyal States.

That under these circumstances and amidst these elements of popular discontent and hostile passion, the

nation should be compelled to plunge into the whirlpool

of a political contest, was felt to be one of the terrible

necessities which might involve the nation's ruin. That

the nation went through it, with a majestic calmness up

to that time unknown, and came out from it stronger,

more resolute, and more thoroughly united than ever before, is among the marvels which confound all theory, and

demonstrate to the world the capacity of an intelligent

people to provide for every conceivable emergency in the

conduct of their own affairs.

Preparations for the nomination of candidates had be

gun to be made, as usual, early in the spring of 1864.

Some who saw most clearly the necessities of the future,

had for some months before expressed themselves strongly

in favor of the renomination of President Lincoln. But

this step was contested with great warmth and activity

by prominent members of the political party by which

he had been nominated and elected four years before.

Nearly all the original Abolitionists and many of the more

decidedly anti-slavery members of the Republican party

were dissatisfied, that Mr. Lincoln had not more rapidly

and more sweepingly enforced their extreme opinions.

Many distinguished public men resented his rejection of

their advice, and many more had been alienated by his

inability to recognize their claims to office. The most violent

opposition came from those who had been most

persistent and most clamorous in their exactions. And as

it was unavoidable that, in wielding so terrible and so

absolute a power in so terrible a crisis, vast multitudes

of active and ambitious men should be disappointed in

their expectations of position and personal gain, the

renomination of Mr. Lincoln was sure to be contested by

a powerful and organized effort.

At the very outset this movement acquired consistency

and strength by bringing forward the Hon. S. P. Chase,

Secretary of the Treasury, a man of great political boldness and experience, and who had prepared the way for

such a step by a careful dispensation of the vast patronage of his department, as the rival candidate. But it was

instinctively felt that this effort lacked the sympathy and

support of the great mass of the people, and it ended in

the withdrawal of his name as a candidate by Mr. Chase

himself.

The National Committee of the Union Republican party.

had called their convention, to be held at Baltimore, on

the 8th of June. This step had been taken from a conviction of the wisdom of terminating as speedily as

possible all controversy concerning candidates in the

ranks of Union men; and it was denounced with the

greatest vehemence by those who opposed Mr. Lincoln's

nomination, and desired more time to infuse their hostility

into the public mind. Failing to secure a postponement

of the convention, they next sought to overawe and dictate its action by a display of power, and the following

call was accordingly issued about the 1st of May, for a

convention to be held at Cleveland, Ohio, on the 31st day.

of that month:--

TO THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED

STATES.

After having labored ineffectually to defer, as far

as was in our power,

the critical moment when the attention of the people must inevitably

be

fixed upon the selection of a candidate for the chief magistracy of

the

country; after having interrogated our conscience and consulted our

duty

as citizens, obeying at once the sentiment of a mature conviction

and a

profound affection for the common country, we feel ourselves

impelled,

on our own

responsibility, to declare to the people that the time has

come for all independent men, jealous of their liberties and of the

national

greatness, to confer together, and unite to resist the swelling

invasion of

an open, shameless, and unrestrained patronage, which threatens to

in gulf under its destructive wave the rights of the people, the

liberty and

dignity of the nation.

Deeply impressed with the conviction that, in a

time of revolution,

when the public attention is turned exclusively to the success of

armies,

and is consequently less vigilant of the public liberties, the

patronage

derived from the organization of an army of a million of men, and an

administration of affairs which seeks to control the remotest parts

of the

country in favor of its supreme chief, constitute a danger seriously

threatening the stability of republican institutions, we declare

that the

principle of one term, which has now acquired nearly the force of

law

by the consecration of time, ought to be inflexibly adhered to in

the approaching election.

We further declare, that we do not recognize in the

Baltimore Convention the essential conditions of a truly National Convention. Its

proximity to the centre of all the interested influences of the

administration, its

distance from the centre of the country, its mode of convocation,

the

corrupting practices to which it has been and inevitably will be

subjected, do not permit the people to assemble there with any expectation of being able to deliberate at full liberty. Convinced as we

are

that, in presence of the critical circumstances in which the nation

is

placed, it is only in the energy and good sense of the people that

the

general safety can be found; satisfied that the only way to consult

it is

to indicate a central position, to which every one may go without

too

much expenditure of means and time, and where the assembled people,

far from all administrative influence, may consult freely and

deliberate

peaceably, with the presence of the greatest possible number of men,

whose known principles guarantee their sincere and enlightened

devotion

to the rights of the people and to the preservation of the true

basis of

republican government,--we earnestly invite our fellow-citizens to

unite

at Cleveland, Ohio, on Tuesday, May 31, current, for consultation

and

concert of action in respect to the approaching Presidential

election.

Two other calls were issued after this, prominent

among the signers of which were some of the Germans

of Missouri and some of the old Radical Abolitionists of

the East.

The convention thus summoned met at the appointed

time, about one hundred and fifty in number. No call had

ever been put forward for the election of delegates to it,

and no one could tell whether its members represented any constituency

other than themselves. They came from

fifteen different States and the District of Columbia, but

every one knew that at the East the movement had no

strength whatever. An effort was made by some of

them to bring forward the name of General Grant as a

candidate, but the friends of Fremont formed altogether

too large a majority for that.

General John Cochrane, of New York, was chosen to

preside over the convention. In the afternoon the platform was presented, consisting of thirteen brief resolutions, favoring the suppression of the rebellion, the preservation of the habeas

corpus, of the right of asylum, and

the Monroe doctrine, recommending amendments of the

Constitution to prevent the re-establishment of slavery,

and to provide for the election of President and Vice-President for a single term only, and by the direct vote

of the people, and also urging the confiscation of the

lands of the rebels and their distribution among the soldiers and actual settlers.

The platform having been adopted, the convention proceeded to nominate General Fremont for President by

acclamation. General Cochrane was nominated for Vice-President. The title of "The Radical Democracy" was

chosen for the supporters of the ticket, a National Committee was appointed, and the convention adjourned.

General Fremont's letter of acceptance was dated June

4th. Its main scope was an attack upon Mr. Lincoln for

unfaithfulness to the principles he was elected to defend,

and upon his Administration for incapacity and selfishness,

and for what the writer called "its disregard of constitutional rights, its violation of personal liberty and the

liberty of the press, and, as a crowning shame, its abandonment of the right of asylum, dear to all free nations

abroad."

The platform he approved, with the exception of the

proposed confiscation. He intimated that if the Baltimore Convention would nominate any one but Mr. Lincoln he would not stand in the way of a union of all upon

that nominee; but said, "If Mr. Lincoln be renominated, as I believe it

would be fatal to the country to indorse a

policy and renew a power which has cost us the lives of

thousands of men and needlessly put the country on the

road to bankruptcy, there will remain no alternative but to

organize against him every element of conscientious opposition, with the view to prevent the misfortune of his

re-election." And he accepted the nomination, and announced that he had resigned his commission in the

army.

The convention, the nomination, and the letter of acceptance, fell dead upon the popular feeling. The time

had been when Fremont's name had power, especially

with the young men of the country. Many had felt that

he had received less than he deserved at the hands of

the Administration, and that if the opportunity had been

afforded he would have rendered to the country distinguished and valuable service. But the position which he

had here taken at once separated him from those who had

been his truest friends, whose feelings were accurately

expressed by Governor Morton, of Indiana, in a speech at

Indianapolis on the 12th of June, when he said: "I carried the standard of General Fremont to the best of my

poor ability through the canvass of 1856, and I have

since endeavored to sustain him, not only as a politician,

but as a military chieftain, and never until I read this

letter did I have occasion to regret what I have done. It

has been read with joy by his enemies and with pain by

his friends, and, omitting one or two sentences, there is

nothing in it that might not have been written or subscribed without inconsistency by Mr. Vallandigham."

The next form which the effort to prevent Mr. Lincoln's nomination and election took, was an effort to bring

forward General Grant as a candidate. A meeting had

been called for the 4th of June, in New York, ostensibly

to express the gratitude of the nation to him and the soldiers under his command, for their labors and successes.

As a matter of course the meeting was large and enthusiastic. President Lincoln wrote the following letter in

answer to an invitation to attend:--

EXECUTIVE MANSION, WASHINGTON, June 3,

1864.

Hon. F. A. CONKLING and others:

GENTLEMEN:--Your letter, inviting me to be present at a mass meeting of loyal citizens, to be held at New York, on the 4th instant,

for the purpose of expressing gratitude to Lieutenant-General Grant for

his signal services, was received yesterday. It is impossible for me to

attend. I approve, nevertheless, of whatever may tend to strengthen and

sustain General Grant and the noble armies now under his direction.

My previous high estimate of General Grant has been maintained and

heightened by what has occurred in the remarkable campaign he is now

conducting, while the magnitude and difficulty of the task before him

does not prove less than I expected. He and his brave soldiers are now

in the midst of their great trial, and I trust that at your meeting you

will so shape your good words that they may turn to men and guns,

moving to his and their support.

Whatever political purposes prompted the call for this

meeting, they were entirely overborne by the simple but

resistless appeal, made by the President in this letter, to

the patriotism of the country. Its effect was to stimulate

instantly and largely the effort to fill up the ranks of the

army, and thus aid General Grant in the great campaign

by which he hoped to end the war. In a private letter

to a personal friend, however, General Grant put a

decisive check upon all these attempts of politicians to

make his name the occasion of division among Union

men, by peremptorily refusing to allow himself to be

made a candidate, and by reiterating in still more emphatic

and hopeful terms the President's appeal to the people

for aid and support.

None of these schemes of ambitious aspirants to political leadership had any effect upon the settled sentiment

and purpose of the great body of the people. They

appreciated the importance of continuing the administration of the government in the same channel, and saw

clearly enough that nothing would more thoroughly

impress upon the rebels and the world the determination

of the people to preserve the Union at all hazards, and at

whatever cost, than the indorsement by a popular vote,

in spite of all mistakes and defects of policy, of the President, by

whom the war had thus far been conducted.

The nation, moreover, had entire faith in his integrity,

his sagacity, and his unselfish devotion to the public

good.

The Union and Republican Convention met at Baltimore on the day appointed, the 8th of June. It numbered

nearly five hundred delegates, chosen by the constituents

of each Congressional district of the loyal States, and by

the people in Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas, in

which the rebel authority had been overthrown, and

who sought thus to renew their political relations with

the parties of the Union. The Rev. Robert J. Breckinridge, of Kentucky, was appointed temporary chairman,

and aroused the deepest enthusiasm of the convention

by his patriotic address on taking the chair. He proclaimed openly his hostility to slavery, and demanded, as

essential to the existence of the nation, the complete

overthrow of the rebellion, and condign punishment for

the traitors by whom it had been set on foot. In reference to the nomination of a presidential candidate, he

simply expressed the common sentiment when he said:--

Nothing can

be more plain than the fact that you are here as representatives of a great nation--voluntary representatives, chosen

with out forms of law, but as really representing the feelings and

principles,

and, if you choose, the prejudices of the American people, as if it

were

written in their laws and already passed by their votes. For the man

that you will nominate here for the Presidency of the United States

and

ruler of a great people, in a great crisis, is just as certain, I

suppose,

to become that ruler as any thing under heaven is certain before it

is

done. And moreover you will allow me to say, though perhaps it is

hardly strictly proper that I should, but as far as I know your opin ions, I suppose it is just as certain now, before you utter it,

whose name

you will utter--one which will be responded to from one end to the

other of this nation, as it will be after it has been uttered and

recorded

by your secretary."

The permanent organization was effected in the

afternoon, by the choice of Hon. William Dennison, Ex-Governor of Ohio, as president, with twenty-three vice-presidents, each from a different State, and twenty-three secretaries.

After a speech from Governor Dennison, and

another from Parson Brownlow, of Tennessee, the convention adjourned till Wednesday morning at nine

o'clock.

The first business which came up when the convention reassembled, was the report of the Committee on

Credentials. There were two important questions which

arose upon this report. The first was the Missouri question--there being a double delegation present from that

State. The committee had reported in favor of admitting

the delegation called the Radical Union Delegation to

seats in the convention, as the only one elected in conformity with usage and in regular form. An effort was

made to modify this by admitting both delegations to seats,

and allowing them to cast the vote of the State only in

case of their agreement. This proposition, however, was

voted down by a large majority, and the report of the

committee on that point was adopted. This result had

special importance in its bearing upon the vexed state of

politics in Missouri, which had hitherto, as we have seen,

caused Mr. Lincoln much trouble.

The next question, which had still greater importance,

related to the admission of the delegations from Tennessee,

Arkansas, and Louisiana. Congress had passed a resolution substantially excluding States which had been in rebellion from participation in national affairs until specifically readmitted to the Union--while it was known that

President Lincoln regarded all ordinances of secession as

simply null and void, incapable of affecting the legal relations of the States to the National Government. At the

very opening of the convention an effort had been made

by Hon. Thaddeus Stevens, of Pennsylvania, to secure

the adoption of a resolution against the admission of delegates from any States thus situated. This, however, had

failed, and the whole matter was referred to the Committee

on Credentials, of which Hon. Preston King, of New

York, had been appointed chairman. Mr. King, on behalf of this committee and under its instructions, reported

in favor of admitting these delegates to seats, but without giving them

the right to vote. Mr. King, for himself,

however, and as the only member of the committee who

dissented from its report, moved to amend it by giving

them equal rights in convention with delegates from the

other States. This amendment was adopted by a large

majority, and affected in a marked degree the subsequent

action of the convention. The report was further amended so as to admit delegates from the Territories of Colorado, Nebraska, and Nevada, and also from Florida and

Virginia, without the right to vote--and excluding a

delegation from South Carolina. Thus amended it was

adopted.

Mr. H. J. Raymond, of New York, as chairman of the

Committee on Resolutions, then reported the following

declaration of principles and policy for the Union and

Republican party:--

THE BALTIMORE

PLATFORM.

Resolved, That it is the highest duty of

every American citizen to

maintain, against all their enemies, the integrity of the Union and

the par amount authority of the Constitution and laws of the United States;

and

that, laying aside all differences of political opinion, we pledge

our selves as Union men, animated by a common sentiment and aiming at a

common object, to do every thing in our power to aid the Government

in quelling by force of arms the rebellion now raging against its

author ity, and in bringing to the punishment due to their crimes the

rebels and

traitors arrayed against it.

Resolved, That we approve the determination

of the Government of

the United States not to compromise with rebels, or to offer any

terms of

peace except such as may be based upon an unconditional surrender of

their hostility and a return to their just allegiance to the

Constitution

and laws of the United States; and that we call upon the Government

to maintain this position and to prosecute the war with the utmost

pos sible vigor to the complete suppression of the rebellion, in full

reliance

upon the self-sacrificing patriotism, the heroic valor, and the

undying

devotion of the American people to their country and its free

institutions.

Resolved, That as slavery was the cause and

now constitutes the

strength of this rebellion, and as it must be always and everywhere

hostile to the principles of republican government, justice and the

national

safety demand its utter and complete extirpation from the soil of

the

republic; and that while we uphold and maintain the acts and

proclamations by which the Government, in its own defence, has aimed

a death blow at this gigantic evil, we are in favor, furthermore, of such an

amendment to the Constitution, to be made by the people, in conformity with its provisions, as shall terminate and forever prohibit

the

existence of slavery within the limits or the jurisdiction of the

United

States.

Resolved, That the

thanks of the American people are due to the soldiers and sailors of the army and the navy, who have perilled their

lives

in defence of their country and in vindication of the honor of its

flag;

that the nation owes to them some permanent recognition of their

patriotism and their valor, and ample and permanent provision for those

of

their survivors who have received disabling and honorable wounds in

the

service of their country; and that the memories of those who have

fallen

in its defence shall be held in grateful and everlasting

remembrance.

Resolved, That we

approve and applaud the practical wisdom, the un selfish patriotism, and the unswerving fidelity to the Constitution

and the

principles of American liberty with which Abraham Lincoln has discharged, under circumstances of unparalleled difficulty, the great

duties

and responsibilities of the Presidential office; that we approve and

indorse, as demanded by the emergency and essential to the

preservation

of the nation, and as within the provisions of the Constitution, the

measures and acts which he has adopted to defend the nation against its

open

and secret foes; that we approve especially the Proclamation of

Emancipation and the employment as Union soldiers of men heretofore held

in slavery; and that we have full confidence in his determination to

carry

these and all other constitutional measures, essential to the

salvation of

the country, into full and complete effect.

Resolved, That we deem

it essential to the general welfare that harmony should prevail in our national councils, and we regard as

worthy

of public confidence and official trust those only who cordially

indorse

the principles proclaimed in these resolutions, and which should

characterize the administration of the Government.

Resolved, That the

Government owes to all men employed in its

armies, without regard to distinction of color, the full protection

of the

laws of war, and that any violation of these laws, or the usages of

civilized nations in time of war, by the rebels now in arms, should be

made

the subject of prompt and full redress.

Resolved, That the

foreign immigration which in the past has added so

much to the wealth, development of resources, and increase of power

of

this nation, the asylum of the oppressed of all nations, should be

fostered

and encouraged by a liberal and just policy.

Resolved, That we are in

favor of a speedy construction of the railroad

to the Pacific coast.

Resolved, That the

national faith, pledged for the redemption of the

public debt, must be kept inviolate, and that for this purpose we

recommend economy and rigid responsibility in the public expenditures,

and a vigorous and just system of taxation, and that it is the duty

of every loyal

State to sustain the credit and promote the use of the national

currency.

Resolved, That we approve the position

taken by the Government,

that the people of the United States can never regard with

indifference

the attempt of any European power to overthrow by force, or to

supplant

by fraud, the institutions of any republican government on the

Western

Continent; and that they will view with extreme jealousy, as

menacing

to the peace and independence of their own country, the efforts of

any

such power to obtain new footholds for monarchical governments, sustained by foreign military force, in near proximity to the United

States.

These resolutions were adopted unanimously and with

great enthusiasm. A motion was then made that Abraham Lincoln be nominated for re-election by acclamation,

but this was afterwards withdrawn, and a ballot taken

in the usual way; the only votes that were not given

for Mr. Lincoln were the twenty-two votes of Missouri,

which, as was explained by the chairman of the delegation, were given under positive instructions for General

Grant. Mr. Lincoln received four hundred and ninety-seven votes, and on motion of Mr. Hume, of Missouri, his

nomination was made unanimous, amid intense enthusiasm.

The contest over the Vice-Presidency was spirited

but brief. The candidates before the convention were

Vice-President Hamlin, Hon. D. S. Dickinson, of New

York, and Andrew Johnson, of Tennessee. The struggle lay however between Mr. Johnson and Mr. Dickinson.

The action of the Convention in admitting the delegates

from Tennessee to full membership had a powerful effect

in determining the result. Mr. Johnson received two

hundred votes on the first call of the States, and it being

manifest that he was to be the nominee, other States

changed, till the vote, when declared, stood four hundred

and ninety-two for Johnson, seventeen for Dickinson, and

nine for Hamlin.

The National Executive Committee was then appointed,

and the convention adjourned. On Thursday, June 9,

the committee appointed to inform Mr. Lincoln of his

nomination waited upon him at the White House. Governor Dennison, the President of the Convention and Chairman of the

Committee, addressed him as follows:--

MR.

PRESIDENT:--The National Union Convention, which closed its

sittings at Baltimore yesterday, appointed a committee, consisting

of one

from each State, with myself as chairman, to inform you of your

unanimous nomination by that convention for election to the officer of

President

of the United States. That committee, I have the honor of now

informing you, is present. On its behalf I have also the honor of

presenting you

with a copy of the resolutions or platform adopted by that

convention, as

expressive of its sense and of the sense of the loyal people of the

country

which it represents, of the principles and policy that should

characterize

the administration of the Government in the present condition of the

country. I need not say to you, sir, that the convention, in thus

unanimously nominating you for re-election, but gave utterance to the

almost

universal voice of the loyal people of the country. To doubt of your

triumphant election would be little short of abandoning the hope of

a final

suppression of the rebellion and the restoration of the government

over the

insurgent States. Neither the convention nor those represented by

that

body entertained any doubt as to the final result, under your

administration, sustained by the loyal people, and by our noble army and

gallant

navy. Neither did the convention, nor do this committee, doubt the

speedy suppression of this most wicked and unprovoked rebellion.

[A copy of the resolutions, which had been adopted,

was here handed

to the President.]

I would add, Mr. President, that it would be the

pleasure of the committee to communicate to you within a few days, through one of its

most

accomplished members, Mr. Curtis, of New York, by letter, more at

length

the circumstances under which you have been placed in nomination for

the Presidency.

The President said in response:--

MR. CHAIRMAN

AND GENTLEMEN OF THE COMMITTEE:--I will neither

conceal my gratification, nor restrain the expression of my

gratitude, that

the Union people, through their convention, in the continued effort

to

save and advance the nation, have deemed me not unworthy to remain

in

my present position. I know no reason to doubt that I shall accept

the

nomination tendered; and yet, perhaps, I should not declare

definitely

before reading and considering what is called the platform. I will

say

now, however, that I approve the declaration in favor of so amending

the

Constitution as to prohibit slavery throughout the nation. When the

people in revolt, with the hundred days' explicit notice that they

could

within those days resume their allegiance without the overthrow of

their

institutions, and that they could not resume it afterward, elected

to stand

out, such an amendment of the Constitution as is now proposed became

a fitting and necessary conclusion to the final success of the Union

cause.

Such alone can meet and cover all cavils. I now perceive its

importance

and embrace it. In the joint names of Liberty and Union let us labor

to

give it legal form and practical effect.

At the conclusion of the President's speech, all of the

committee shook him cordially by the hand and offered

their personal congratulations.

On the same afternoon a deputation from the National

Union League waited upon the President, and the chairman addressed him as follows:--

MR.

PRESIDENT:--I have the honor of introducing to you the representatives of the Union League of the Loyal States, to congratulate

you

upon your renomination, and to assure you that we will not fail at

the polls

to give you the support that your services in the past so highly

deserve.

We feel honored in doing this, for we are assured that we are aiding

in

re-electing to the proud position of President of the United States

one so

highly worthy of it--one among not the least of whose claims is that

he

was the emancipator of four millions of bondmen.

The President replied as follows:--

GENTLEMEN:--I

can only say in response to the remarks of your chair man, that I am very grateful for the renewed confidence which has

been

accorded to me, both by the convention and by the National League. I

am not insensible at all to the personal compliment there is in

this, yet I

do not allow myself to believe that any but a small portion of it is

to be

appropriated as a personal compliment to me. The convention and the

nation, I am assured, are alike animated by a higher view of the

interests of

the country, for the present and the great future, and the part I am

entitled

to appropriate as a compliment is only that part which I may lay

hold of as

being the opinion of the convention and of the League, that I am not

en tirely unworthy to be intrusted with the place I have occupied for

the

last three years. I have not permitted myself, gentlemen, to

conclude

that I am the best man in the country; but I am reminded in this

connection of a story of an old Dutch farmer, who remarked to a

companion

once that "it was not best to swap horses when crossing a stream."

On the evening of the same day the President was serenaded by the delegation from Ohio, and to them and

the large crowd which had gathered there, he made the

following brief speech:--

GENTLEMEN:--I

am very much obliged to you for this compliment. I

have just being saying, and will repeat it, that the hardest of all

speeches I have to answer is a serenade. I never know what to say on

these occasions. I suppose that you have done me this kindness in connection

with

the action of the Baltimore Convention, which has recently taken

place,

and with which, of course, I am very well satisfied. What we want

still

more than Baltimore Conventions, or Presidential elections, is

success

under General Grant. I propose that you constantly bear in mind that

the support you owe to the brave officers and soldiers in the field

is of the

very first importance, and we should therefore bend all our energies

to that

point. Now without detaining you any longer, I propose that you help

me

to close up what I am now saying with three rousing cheers for

General

Grant and the officers and soldiers under his command.

The rousing cheers were given--Mr. Lincoln himself

leading off, and waving his hat as earnestly as any one

present.

The written address of the Committee of the Convention

announcing his nomination, sent to him a few days afterwards, was as follows:--

NEW YORK, June 14,

1864.

Hon. ABRAHAM LINCOLN:

SIR:--The National Union Convention, which

assembled in Baltimore

on June 7th, 1864, has instructed us to inform you that you were

nominated with enthusiastic unanimity for the Presidency of the United

States

for four years from the 4th of March next.

The resolutions of the convention, which we have

already had the

pleasure of placing in your hands, are a full and clear statement of

the

principles which inspired its action, and which, as we believe, the

great

body of Union men in the country heartily approve. Whether those

resolutions express the national gratitude to our soldiers and

sailors, or

the national scorn of compromise with rebels, and consequent

dishonor,

or the patriotic duty of union and success; whether they approve the

Proclamation of Emancipation, the Constitutional Amendment, the employment of former slaves as Union soldiers, or the solemn

obligation of

the Government promptly to redress the wrongs of every soldier of

the

Union, of whatever color or race; whether they declare the

inviolability

of the plighted faith of the nation, or offer the national

hospitality to the

oppressed of every land, or urge the union by railroad of the

Atlantic and

Pacific Oceans; whether they recommend public economy and vigorous

taxation, or assert the fixed popular opposition to the

establishment by

armed force of foreign monarchies in the immediate neighborhood of

the

United States, or declare that those only are worthy of official

trust who

approve unreservedly the views and policy indicated in the

resolutions- they were equally hailed with the heartiness of profound conviction.

Believing with you, sir, that this is the people's

war for the maintenance

of a Government which you have justly described as "of the people,

by

the people, for the people," we are very sure that you will be glad to

know, not only from the resolutions themselves, but from the singular

harmony and enthusiasm with which they were adopted, how warm is

the popular welcome of every measure in the prosecution of the war

which is as vigorous, unmistakable, and unfaltering as the national purpose itself. No right, for instance, is so precious and sacred to the

American heart as that of personal liberty. Its violation is regarded

with just, instant, and universal jealousy. Yet, in this hour of peril,

every faithful citizen concedes that, for the sake of national existence

and

the common welfare, individual liberty may, as the Constitution provides

in case of rebellion, be sometimes summarily constrained, asking only

with painful anxiety that in every instance, and to the least detail,

that

absolute necessary power shall not be hastily or unwisely exercised.

We believe, sir, that the honest will of the Union men of the country

was never more truly represented than in this convention. Their purpose we believe to be the overthrow of armed rebels in the field, and

the

security of permanent peace and union, by liberty and justice, under the

Constitution. That these results are to be achieved amid cruel perplexities, they are fully aware. That they are to be reached only through

cordial unanimity of counsel, is undeniable. That good men may sometimes differ as to the means and the time, they know. That in the

conduct of all human affairs the highest duty is to determine, in the

angry conflict of passion, how much good may be practically accomplished, is their sincere persuasion. They have watched your official

course, therefore, with unflagging attention; and amid the bitter taunts

of eager friends and the fierce denunciation of enemies, now moving too

fast for some, now too slowly for others, they have seen you throughout

this tremendous contest patient, sagacious, faithful, just--leaning upon

the heart of the great mass of the people, and satisfied to be moved by

its

mighty pulsations.

It is for this reason that, long before the convention met, the popular

instinct indicated you as its candidate; and the convention, therefore,

merely recorded the popular will. Your character and career prove

your unswerving fidelity to the cardinal principles of American liberty

and of the American Constitution. In the name of that liberty and Constitution, sir, we earnestly request your acceptance of this nomination;

reverently commending our beloved country, and you, its Chief Magistrate, with all its brave sons who, on sea and land, are faithfully

defending the good old American cause of equal rights, to the blessing of

Almighty God.

We are, sir, very respectfully, your friends and fellow-citizens.

|

WM. DENNISON, O.,

Chairman. |

W. BUSHNELL, Ill. |

|

JOSIAH DRUMMOND,

Maine. |

L. P. ALEXANDER, Mich. |

|

THOS. E. SAWYER,

N. H. |

A. W. RANDALL, Wis. |

|

BRADLEY BARLOW,

Vt. |

A. OLIVER, Iowa. |

| A.

H. BULLOCK, Mass. |

THOMAS SIMPSON, Minn. |

| A.

M. GAMMELL, R. I. |

JOHN BIDWELL, Cal. |

| C.

S. BUSHNELL, Conn. |

THOMAS H. PEARNE, Oregon |

| G.

W. CURTIS, N. Y. |

LEROY KRAMER, West Va. |

| W.

A. NEWELL, N. J. |

A. C. WILDER, Kansas. |

|

HENRY JOHNSON, Penn. |

M. M. BRIEN, Tennessee. |

| N.

B. SMITHERS, Del. |

J. P. GREVES, Nevada. |

| W.

L. W. SEABROOK, Md. |

A. A. ATOCHA, La. |

|

JOHN F. HUME, Mo. |

A. S. PADDOCK, Nebraska. |

| G.

W. HITE, Ky. |

VALENTINE DELL, Arkansas. |

| E.

P. TYFFE, Ohio. |

JOHN A. NYE, Colorado. |

|

CYRUS M. ALLEN, Ind. |

A. B. SLOANAKER, Utah. |

REPLY OF MR. LINCOLN.

EXECUTIVE MANSION,

WASHINGTON, June 27,

1864.

HON. WM. DENNISON and others, a Committee of the

Union National Convention:

GENTLEMEN:--Your letter of the 14th inst., formally

notifying me that

I have been nominated by the convention you represent for the Presidency of the United States for four years from the 4th of March

next, has

been received. The nomination is gratefully accepted, as the

resolutions

of the convention, called the platform, are heartily approved.

While the resolution in regard to the supplanting

of republican government upon the Western Continent is fully concurred in, there might

be

misunderstanding were I not to say that the position of the

Government

in relation to the action of France in Mexico, as assumed through

the

State Department and indorsed by the convention among the measures

and acts of the Executive, will be faithfully maintained so long as

the

state of facts shall leave that position pertinent and applicable.

I am especially gratified that the soldier and

seaman were not forgotten

by the convention, as they forever must and will be remembered by

the

grateful country for whose salvation they devote their lives.

Thanking you for the kind and complimentary terms

in which you

have communicated the nomination and other proceedings of the convention, I subscribe myself,

Your obedient servant,

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

The platform adopted by the Baltimore Convention

met with the general approval of those of the people who

claimed to be the supporters of the Government. One

exception was, however, found in the person of Mr.

Charles Gibson, Solicitor of the United States in the Court of Claims at

St. Louis, who, considering, as he

said, that that platform rendered his retention of office

under Mr. Lincoln's Administration wholly useless to the

country, as well as inconsistent with his principles, tendered his resignation, through the clerk of the Court of

Claims, Mr. Welling.

The President's reply, communicated through his private secretary, was

as follows:--

EXECUTIVE MANSION, WASHINGTON, July 25,1864.

J. C. WELLING, ESQ.:--

According to the request contained in your note, I

have placed Mr.

Gibson's letter of resignation in the hands of the President. He has

read the letter, and says he accepts the resignation, as he will be

glad to

do with any other, which may be tendered, as this is, for the

purpose of

taking an attitude of hostility against him.

He says he was not aware that he was so much

indebted to Mr. Gibson

for having accepted the office at first, not remembering that he

ever

pressed him to do so, or that he gave it otherwise than as usual,

upon a

request made on behalf of Mr. Gibson.

He thanks Mr. Gibson for his acknowledgment that he

has been treated

with personal kindness and consideration, and he says he knows of

but

two small drawbacks upon Mr. Gibson's right to still receive such

treatment, one of which is that he could never learn of his giving much

attention to the duties of his office, and the other is this studied

attempt

of Mr. Gibson's to stab him.

I am, very truly,

Your obedient servant,

JOHN HAY.

The elements of opposition to Mr. Lincoln's election in

the ranks of his own party were checked, though not

wholly destroyed, by the unanimity of his nomination.

Conferences were still held among prominent men, especially in the city of New York, for the purpose of organizing this hostility and making it effective, and a call was

put in circulation for a convention to be held at Cincinnati, to put in nomination another candidate. The movement, however, was so utterly destitute of popular sympathy that it was soon abandoned. A very sharp and

acrimonious warfare was still waged upon Mr. Lincoln

and his Administration not only by the leading presses

of the opposition, but by prominent men and influential journals

ostensibly in the ranks of his supporters. Every

act of the government was canvassed with eager and unfriendly scrutiny, and made, wherever it was possible, the

ground of hostile assault.

Among the matters thus seized upon was the surrender to the Spanish authorities of a Cuban named

Arguelles, which was referred to by the Fremont Convention as a denial of the right of asylum. This man,

Don Jose Augustine Arguelles, was a colonel in the

Spanish army, and Lieutenant-Governor of the District

of Colon, in Cuba. As such, in November, 1863, he

effected the capture of a large number of slaves that were

landed within his district, and received from the Government of Cuba praise for his efficiency, and the sum of

fifteen thousand dollars for his share of prize-money on

the capture. Shortly afterwards, he obtained leave of

absence for twenty days, for the purpose of going to New

York and there making the purchase of the Spanish

newspaper called La

Cronica. He came to New York,

and there remained. In March following, the Cuban

Government made application to our authorities, through

the Consul-General's office at Havana, stating that it had

been discovered that Arguelles, with others, had been

guilty of the crime of selling one hundred and forty-one

of the cargo of negroes thus captured, into slavery, and

by means of forged papers representing to the Government that they had died after being landed; stating also

that his return to Cuba was necessary to procure the

liberation of his hapless victims, and desiring to know

whether the Government of the United States would

cause him to be returned to Cuba. Documents authenticating the facts of the case were forwarded to our

authorities. There being no extradition treaty between

our country and Spain, the Cuban Government could

take no proceedings before the courts in the matter,

and the only question was whether our Government

would take the responsibility of arresting Arguelles and

sending him back or not. The Government determined

to assume the responsibility, and sent word to the Cuban authorities

that if they would send a suitable officer to

New York, measures would be taken to place Arguelles

in his charge. The officer was sent, and Arguelles having been arrested by the United States Marshal at

New York, was, before any steps could be taken to

appeal to any of the courts on his behalf, put on board a

steamer bound for Havana. This proceeding caused

great indignation until the facts were understood. Arguelles having money, had found zealous friends in

New York, and a strong effort was made in his favor.

It was stated on his behalf that, instead of being

guilty of selling these negroes into slavery, it was the

desire of the Cuban authorities to get possession of him

and silence him, lest he should publish facts within his

knowledge which implicated the authorities themselves

in that nefarious traffic. And the fact that he was taken

as he was, by direct order of the Government, not by any

legal or judicial proceedings, and without having the

opportunity to test before the courts the right of the

Government thus to send back any one, however criminal,

was alleged to spring from the same disregard of liberty

and law in which the arbitrary arrests which had been

made of rebel sympathizers were said to have had their

source. Proceedings were even taken against the United

States Marshal under a statute of the State of New York

against kidnapping, and everywhere the enemies of the

Administration found in the Arguelles case material for

assailing it as having trampled upon the right of asylum,

exceeded its own legal powers, insulted the laws and

courts of the land, and endangered the liberties of the

citizen; while the fact of its having aided in the punishment of an atrocious crime, a crime intimately connected

with the slave-trade, so abhorrent to the sympathies of

the people, was kept out of sight.

Another incident used to feed the public distrust of

the Administration, was the temporary suppression of

two Democratic newspapers in the city of New York.

On Wednesday, May 18th, these two papers, the World

and the Journal of

Commerce, published what purported to be a proclamation of President

Lincoln. At this time,

as will be recollected, General Grant was still struggling

with Lee before Spottsylvania, with terrible slaughter

and doubtful prospects, while Sigel had been driven

back by Imboden, and Butler was held in check by

Beauregard. This proclamation announced to the country that General Grant's campaign was virtually closed;

and, "in view of the situation in Virginia, the disaster at

Red River, the delay at Charleston, and the general state

of the country," it appointed the 26th of May as a day

of fasting, humiliation, and prayer, and ordered a fresh

draft of four hundred thousand men. The morning of its

publication was the day of the departure of the mails for

Europe. Before its character was discovered, this forged

proclamation, telegraphed all over the country, had

raised the price of gold five or six per cent., and carried discouragement and dismay to the popular heart.

The suppression of the papers by which it had been

published, the emphatic denial of its authenticity, and

the prompt adoption of measures to detect its author,

speedily reassured the public mind. After being satisfied that the publication of the document was inadvertent, the journals seized were permitted to resume publication, the authors of the forgery were sent to Fort

Lafayette, and public affairs resumed their ordinary

course.

But the action of the Government gave fresh stimulus

to the partisan warfare upon it. As in the Arguelles case

and the arbitrary arrests it had been charged with trampling upon the liberties of the citizen, so now it was charged

with attacking the liberty of the press. Governor

Seymour directed the District Attorney of New York to

take measures for the prosecution and punishment of all

who had been connected with shutting up the newspaper

offices. The matter was brought before a grand-jury,

which reported that it was inexpedient to examine into

the subject."

Determined not to be thus thwarted, Governor Seymour, alleging that the grand-jury had disregarded their oaths, directed

the District Attorney to bring the subject

before some magistrate. Warrants were accordingly

issued by City Judge Russell for the arrest of General

Dix and the officers who had acted in the matter. The

parties voluntarily appeared before the judge, and an

argument of the legal questions involved was had. The

judge determined to hold General Dix and the rest for

the action of the grand-jury. One grand-jury, however,

had already refused to meddle with the matter, and,

greatly to the disappointment of those who had aimed

to place the State of New York in a position of open

hostility to the Government of the United States, no further proceedings were ever taken in the matter.

An effort was made to bring the subject up in Congress. Among other propositions, Mr. Brooks, of New

York, proposed to add, as an amendment to a bill for

the incorporation of a Newsboys' Home in the District of

Columbia, a provision that no newspaper should be suppressed in Washington, or its editor incarcerated, without

due process of law. He succeeded in making a speech

abounding in denunciations of the Government, but had

no other success.

To those men at the North who really sympathized with

the South on the slavery question, the whole policy of

the Administration upon that subject was distasteful.

The Emancipation Proclamation, the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law, and even the employment of negroes in

the army, were with them grave causes of complaint

against it. The President's views on this matter were

expressed in the following conversational remarks, to some

prominent Western gentlemen:--

The slightest

knowledge of arithmetic (said he) will prove to any

man that the rebel armies cannot be destroyed by Democratic

strategy.

It would sacrifice all the white men of the North to do it. There

are

now in the service of the United States nearly two hundred thousand

able-bodied colored men, most of them under arms, defending and ac quiring Union territory. The Democratic strategy demands that these

forces be disbanded, and that the masters be conciliated by

restoring them

to slavery. The black men who now assist Union prisoners to escape

are to be converted into our enemies, in the vain hope of gaining

the

good-will of their masters. We shall have to fight two nations

instead

of one.

You cannot conciliate the South if you guarantee to

them ultimate

success, and the experience of the present war proves their success

is

inevitable if you fling the compulsory labor of four millions of

black men

into their side of the scale. Will you give our enemies such

military

advantages as insure success, and then depend upon coaxing,

flattery, and

concession to get them back into the Union? Abandon all the forts

now

garrisoned by black men, take two hundred thousand men from our

side,

and put them in the battle-field, or cornfield, against us, and we

would

be compelled to abandon the war in three weeks.

We have to hold territory in inclement and sickly

places. Where are

the Democrats to do this? It was a free fight, and the field was

open to

the War Democrats to put down this rebellion by fighting against

both

master and slave long before the present policy was inaugurated.

There

have been men base enough to propose to me to return to slavery our

black warriors of Port Hudson and Olustee, and thus win the respect

of

the masters they fought. Should I do so, I should deserve to be

damned

in time and eternity. Come what will, I will keep my faith with

friend and

foe. My enemies pretend I am now carrying on this war for the sole

purpose of abolition. So long as I am President it shall be carried

on

for the sole purpose of restoring the Union. But no human power can

subdue this rebellion without the use of the emancipation policy,

and

every other policy calculated to weaken the moral and physical

forces of

the rebellion.

Freedom has given us two hundred thousand men,

raised on Southern

soil. It will give us more yet. Just so much it has abstracted from

the

enemy; and instead of checking the South, there are evidences of a

fraternal feeling growing up between our men and the rank and file of

the

rebel soldiers. Let my enemies prove to the country that the

destruction

of slavery is not necessary to the restoration of the Union. I will

abide

the issue.

Aside from the special causes of attack which we have

mentioned, others were brought forward more general in

their character. The burdens of the war were made

especially prominent. Every thing discouraging was

harped upon and magnified, every advantage was belittled

and sneered at. The call for five hundred thousand men

in June was even deprecated by the friends of the Administration, because of the political capital which its

enemies would be sure to make of it. Nor was Mr. Lincoln himself unaware that such would be the result, but, though

recognizing the elements of dissatisfaction which

it carried with it, he did not suffer himself to be turned

aside in the least from the path which duty to his coutry required him to pursue. The men were needed, he

said, and must be had, and should he fail as a candidate.

for re-election in consequence of doing his duty to the

country, he would have at least the satisfaction of going

down with colors flying.

Financial difficulties were also used in the same way.

The gradual rise in the price of gold was pointed at as

indicating the approach of that financial ruin which

was surely awaiting the country, if the re-election of Mr.

Lincoln should mark the determination of the people to

pursue the course upon which they had entered.

Amidst these assaults from his opponents, Mr. Lincoln

seemed fairly entitled, at least, to the hearty support of

all the members of his own party. And yet this very

time was chosen by Senator Wade, of Ohio, and H.

Winter Davis, of Maryland, to make a violent attack upon

him for the course which he had pursued in reference

to the Reconstruction Bill, which he had not signed, but

had given his reasons for not signing, in his proclamation of July 18th. They charged him with usurpation,

with presuming upon the forbearance of his supporters,

with defeating the will of the people by an Executive

perversion of the Constitution, &c., &c., and closed a

long and violent attack by saying that if he wished their

support he "must confine himself to his Executive

duties--to obey and execute, not make the laws--to suppress by arms armed rebellion, and leave political reorganization to Congress."

This manifesto, prepared with marked ability, and

skilfully adapted to the purpose it was intended to serve,

at first created some slight apprehension among the supporters of the President. But it was very soon felt that

it met with no response from the popular heart, and it

only served to give a momentary buoyancy to the hopes

of the Opposition.

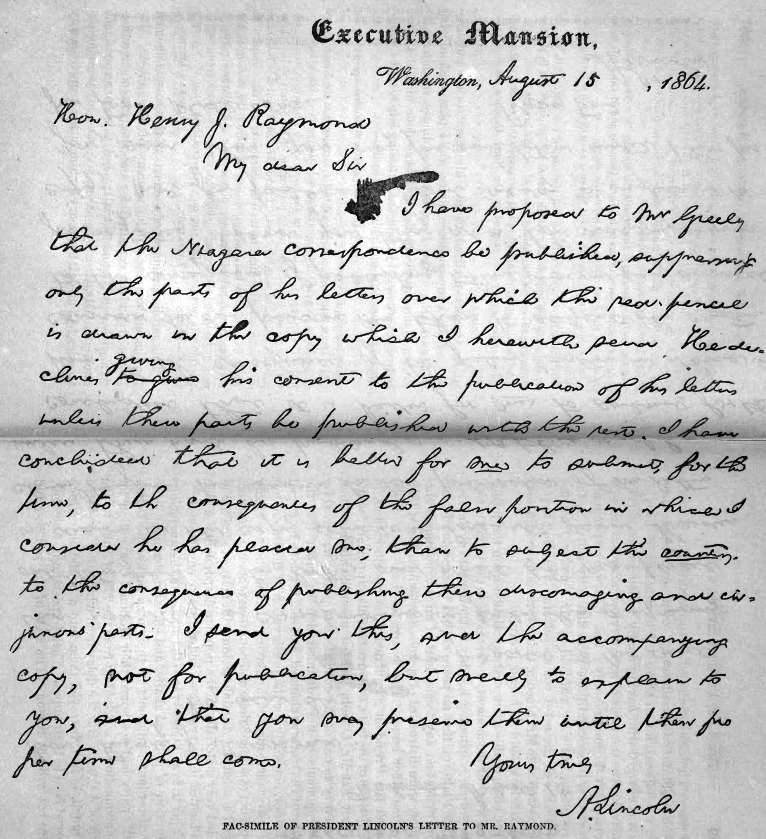

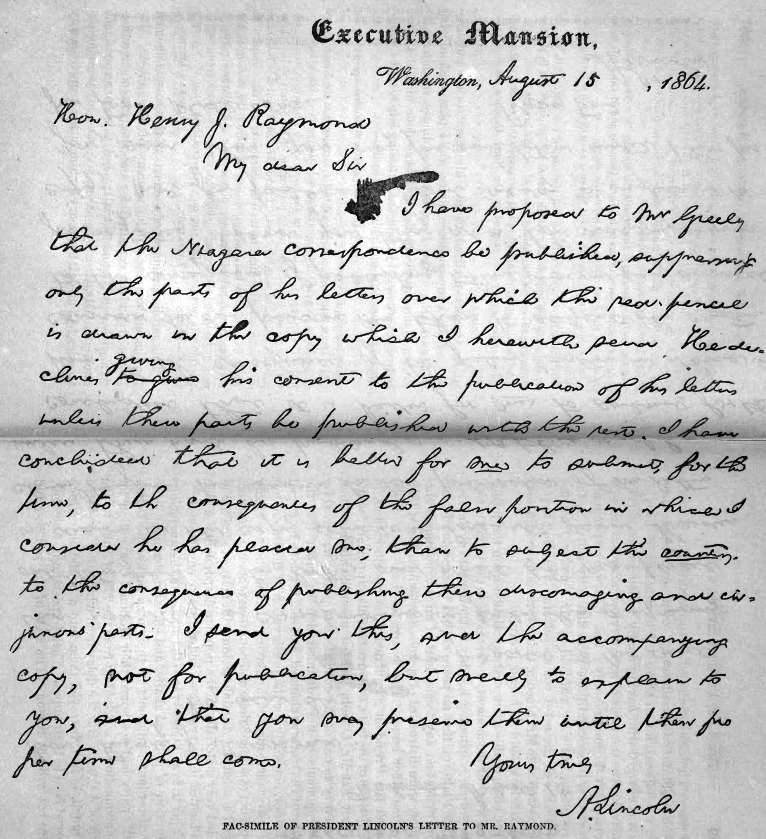

Still another incident soon occurred to excite a considerable degree of

public anxiety concerning the immediate political future. It was

universally understood that a strong desire for peace pervaded the

public mind, and. that the determination to prosecute the war was

the dictate of duty, rather than inclination. To such an extent

did this longing for peace influence the sentiments and action of

some, among the least resolute and hopeful of the political

leaders in the Republican party, that ready access to them was

found by agents of the Rebel Government, stationed in Canada for such active service as circumstances might require. Of these agents, who were

then at Niagara Falls, were C. C. Clay, formerly United

States Senator from Alabama, Professor Holcombe, of Virginia, and George N. Sanders. Acting on their behalf

and under their instructions, W. Cornell Jewett, an irresponsible and half-insane adventurer, had put himself in

communication with Hon. Horace Greeley, Editor of the

New York Tribune, whose intense eagerness for peace had

already commended him to the admiration and sympathy

of the emissaries of the Rebel Government. In reply to

some letter which had been addressed to him, but which

has not yet been made public, Jewett wrote on the 5th of

July to Mr. Greeley the following letter:--

NIAGARA FALLS, July 5,

1864.

MY DEAR MR. GREELEY:--In reply to your note, I have

to advise having just left Hon. George N. Sanders, of Kentucky, on the Canada

side. I

am authorized to state to you, for our use only, not the public,

that two

ambassadors of Davis & Co. are now in Canada, with full and complete

powers for a peace, and Mr. Sanders requests that you come on

immediately to me, at Cataract House, to have a private interview, or if

you

will send the President's protection for

him and two friends, they will

come on and meet you. He says the whole matter can be consummated

by me, you, them, and President Lincoln. Telegraph me in such form

that I may know if you come here, or they to come on with me.

The next day Mr. Jewett also telegraphed as follows:--

H. GREELEY, Tribune:

Will you come here? Parties have full power. Wrote

you yesterday

JEWETT.

This letter and telegram Mr. Greeley enclosed to the

President, at Washington, accompanied by the following letter:--

NEW YORK, July 7,

1864.MY DEAR SIR:--I venture to enclose you a letter and telegraphic

dis patch that I received yesterday from our irrepressible friend,

Colorado

Jewett, at Niagara Falls. I think they deserve attention. Of course

I

do not indorse Jewett's positive averment that his friends at the

Falls

have "full powers" from J. D., though I do not doubt that he thinks

they have. I let that statement stand as simply evidencing the

anxiety

of the Confederates everywhere for peace. So much is beyond

doubt. And therefore I venture to remind you that our bleeding,

bankrupt,

almost dying country also longs for peace--shudders at the prospect

of

fresh conscriptions, of further wholesale devastations, and of new

rivers

of human blood; and a wide-spread conviction that the Government and

its prominent supporters are not anxious for peace, and do not

improve

proffered opportunities to achieve it, is doing great harm now, and

is

morally certain, unless removed, to do far greater in the

approaching

elections. It is not enough that we anxiously desire a true and

lasting peace; we

ought to demonstrate and establish the truth beyond cavil. The fact

that

A. H. Stephens was not permitted a year ago to visit and confer with

the authorities at Washington has done harm, which the tone at the

late

National Convention at Baltimore is not calculated to counteract. I

entreat you, in your own time and manner, to submit overtures for

pacification to the Southern insurgents, which the impartial must

pronounce frank and generous. If only with a view to the momentous election soon to occur in North Carolina, and of the draft to be

enforced in

the Free States, this should be done at once. I would give the

safe-con duct required by the rebel envoys at Niagara, upon their parole to

avoid

observation and to refrain from all communication with their sympathizers in the loyal States; but you may see reasons for declining

it. But

whether through them or otherwise, do not, I entreat you, fail to

make

the Southern people comprehend that you, and all of us, are anxious

for

peace, and prepared to grant liberal terms. I venture to suggest the

following PLAN OF ADJUSTMENT.

|

1. |

The Union is

restored and declared perpetual. |

|

2. |

Slavery is

utterly and forever abolished throughout the same. |

|

3. |

A complete

amnesty for all political offences, with a restoration of all

the inhabitants of each State to all the privileges of

citizens of the United

States. |

|

4. |

The Union to

pay four hundred million dollars ($400,000,000) in five

per cent. United States stock to the late Slave States,

loyal and secession

alike, to be apportioned pro

rata,

according to their slave population respectively, by the

census of 1860, in compensation for the losses of their

loyal citizens by the abolition of slavery. Each State to be

entitled to its quota upon the ratification by its

legislature of this adjustment. The bonds to be at the

absolute disposal of the legislature aforesaid. |

|

5. |

The said Slave

States to be entitled henceforth to representation in the

House on the basis of their total, instead of their federal

population, the

whole now being free. |

|

6. |

A national

convention, to be assembled so soon as may be, to ratify this

adjustment, and make such changes in the Constitution as may

bedeemed advisable. |

Mr.

President, I fear you do not realize how intently the people desire

any peace consistent with the national integrity and honor, and how

joyously they would hail its achievement, and bless its authors.

With

United States stocks worth but forty cents in gold per dollar, and

drafting about to commence on the third million of Union soldiers, can

this

be wondered at?

I do not say that a just peace is now attainable,

though I believe it to

be so. But I do say that a frank offer by you to the insurgents of

terms

which the impartial say ought to be accepted will, at the worst,

prove

an immense and sorely needed advantage to the national cause. It may

save us from a Northern insurrection.

| Yours,

truly, |

HORACE GREELEY. |

Hon. A. LINCOLN, President, Washington,

D. C.

P. S.--Even though it should be deemed unadvisable

to make an offer

of terms to the rebels, I insist that, in any possible case, it is

desirable

that any offer they may be disposed to make should be received, and

either accepted or rejected. I beg you to invite those now at

Niagara to

exhibit their credentials and submit their ultimatum. H. G.

To this letter the President sent the following answer:--

WASHINGTON, D. C., July 9,

1864.

Hon. HORACE GREELEY:

DEAR SIR:--Your letter of the 7th, with enclosures,

received. If you

can find any person anywhere professing to have any proposition of

Jefferson Davis, in writing, for peace, embracing the restoration of

the

Union and abandonment of slavery, whatever else it embraces, say to

him he may come to me with you, and that if he really brings such

prop osition, he shall, at the least, have safe-conduct with the paper

(and with out publicity if he chooses) to the point where you shall have met

him.

The same if there be two or more persons.

Mr. Greeley answered this letter as follows:--

OFFICE OF THE

TRIBUNE, NEW YORK, July 10,

1864.

MY DEAR SIR:--I have yours of yesterday. Whether

there be persons

at Niagara (or elsewhere) who are empowered to commit the rebels by

negotiation, is a question; but if there

be such, there is no question at all

that they would decline to exhibit their credentials to me, much

more to

open their budget and give me their best terms. Green as I may be, I

am

not quite so verdant as to imagine any thing of the sort. I have

neither

purpose nor desire to be made a confidant, far less an agent, in

such negotiations. But I do deeply realize that the rebel chiefs achieved a

most

decided advantage in proposing or pretending to propose to have A.

H.

Stephens visit Washington as a peacemaker, and being rudely

repulsed;

and I am anxious that the ground lost to the national cause by that

mistake shall somehow be regained in season for effect on the

approaching

North Carolina election. I will see if I can get a look into the

hand of

whomsoever may be at Niagara; though that is a project so manifestly

hopeless that I have little heart for it, still I shall try.

Meantime I wish you would consider the propriety of

somehow apprising the people of the South, especially those of North Carolina,

that

no overture or advance looking to peace and reunion has ever been

repelled by you, but that such a one would at. any time have been

cordially

received and favorably regarded, and would still be.

Hon. A.

LINCOLN.

This letter failed to reach the President until after the

following one was received, and was never, therefore,

specifically answered.

Three days after the above letter, Mr. Greeley, having

received additional information from some quarter, wrote

to the President again as follows:--

OFFICE OF THE

TRIBUNE, NEW YORK, July 13,

1864.

MY DEAR SIR:--I have now information on which I can

rely that two

persons duly commissioned and empowered to negotiate for peace are

at

this moment not far from Niagara Falls, in Canada, and are desirous

of

conferring with yourself, or with such persons as you may appoint

and

empower to treat with them. Their names (only given in confidence)

are

Hon. Clement O. Clay, of Alabama, and Hon. Jacob Thompson, of

Mississippi. If you should prefer to meet them in person, they require

safe-con ducts for themselves, and for George N. Sanders, who will accompany

them. Should you choose to empower one or more persons to treat with

them in Canada, they will of course need no safe-conduct; but they

can not be expected to exhibit credentials save to commissioners

empowered

as they are. In negotiating directly with yourself, all grounds of

cavil would be avoided, and you would be enabled at all times to act

upon the

freshest advices of the military situation. You will of course

understand

that I know nothing and have proposed nothing as to terms, and that

nothing is conceded or taken for granted by the meeting of persons

empowered to negotiate for peace. All that is assumed is a mutual

desire

to terminate this wholesale slaughter, if a basis of adjustment can

be mutually agreed on, and it seems to me high time that an effort to

this end

should be made. I am of course quite other than sanguine that a

peace

can now be made, but I am quite sure that a frank, earnest, anxious

effort to terminate the war on honorable terms would immensely

strengthen the Government in case of its failure, and would help us

in the

eyes of the civilized world, which now accuses us of obstinacy, and

indisposition even to seek a

peaceful solution of our sanguinary, devastating

conflict. Hoping to hear that you have resolved to act in the

premises,

and to act so promptly that a good influence may even yet be exerted

on

the North Carolina election next month,

| I remain

yours, |

HORACE GREELEY. |

Hon. A. LINCOLN, Washington.

On the 12th, the day before the foregoing letter was

sent, Mr. George N. Sanders had written to Mr. Greeley

as follows:--

CLIFTON

HOUSE, NIAGARA FALLS,

CANADA WEST, July 12,

1864.

DEAR SIR:--I

am authorized to say that Honorable Clement C. Clay,

of Alabama, Professor James P. Holcombe, of Virginia, and George N.

Sanders, of Dixie, are ready and willing to go at once to

Washington,

upon complete and unqualified protection being given either by the

President or Secretary of War. Let the permission include the three names

and one other.

|

Very respectfully, |

GEORGE N. SANDERS. |

To Hon.

HORACE GREELEY.

This letter of Mr. Sanders does not seem to have been

communicated to the President, but on the receipt of Mr.

Greeley's letter of the 13th, he immediately answered it

by the following telegram:--

EXECUTIVE MANSION, WASHINGTON, July 15,

1864.

HON. HORACE GREELEY, New York:--I suppose you

received my letter

of the 9th. I have just received yours of the 13th, and am

disappointed

by it. I was not expecting you to send me

a letter, but to bring me a

man, or men. Mr. Hay goes to you with my answer to yours of the

13th.

A. LINCOLN.

The answer which Major Hay carried was as follows:--

EXECUTIVE

MANSION, WASHINGTON, July 15,

1864.

Hon. HORACE GREELEY:

MY DEAR SIR:--Yours of the 13th is just received,

and I am disappointed that you have not already reached here with those commisioners. If they would consent to come, on being shown my letter to you

of

the 9th instant, show that and this to them, and if they will come

on the

terms stated in the former, bring them. I not only intend a sincere

effort

for peace, but I intend that you shall be a personal witness that it

is

made.

When Major Hay arrived at New York, he delivered

to Mr. Greeley this letter from the President, and telegraphed its result to the President as follows:--

UNITED STATES MILITARY

TELEGRAPH,

WAR DEPARTMENT, NEW YORK, 9 A.M., July 16,

1864.

His

Excellency A. LINCOLN,

President of the United States:

Arrived this morning at 6 A.M., and delivered your

letter few minutes

after. Although he thinks some one less known would create less excitement and be less embarrassed by public curiosity, still he will

start

immediately if he can have an absolute safe-conduct for four persons

to

be named by him. Your letter he does not think will guard them from

arrest, and with only those letters he would have to explain the

whole

matter to any officer who might choose to hinder them. If this meets

with your approbation, I can write the order in your name as A.

A.-G.

or you can send it by mail. Please answer me at Astor House.

JOHN HAY, A.

A.-G.

The President at once answered by telegraph as follows:--

EXECUTIVE, MANSION,

WASHINGTON, July 16,

1864.

JOHN HAY, Astor House, New York:

Yours received. Write the safe-conduct as you

propose, without wait ing for one by mail from me. If there is or is not any thing in the

affair,

I wish to know it without unnecessary delay. A. LINCOLN.

Major Hay accordingly wrote the following safe-conduct,

armed with which Mr. Greeley betook himself at once to

Niagara Falls:--

EXECUTIVE MANSION, WASHINGTON,

D. C. The President of the United States directs that the four

persons whose

names follow, to wit:

|

|

HON. CLEMENT

C. CLAY, |

|

|

HON. JACOB

THOMPSON, |

|

|

Prof. JAMES

B. HOLCOMBE, |

|

|

GEORGE N.

SANDERS, |

shall have

safe-conduct to the City of Washington in company with the

Hon. Horace Greeley, and shall be exempt from arrest or annoyance of

any kind from any officer of the United States during their journey

to the

said City of Washington.

By order of the President:

JOHN HAY, Major

and A. A.-G.