Domestic Water Fowl

By H. H. Stoddard

Chapter 3

Swans

|

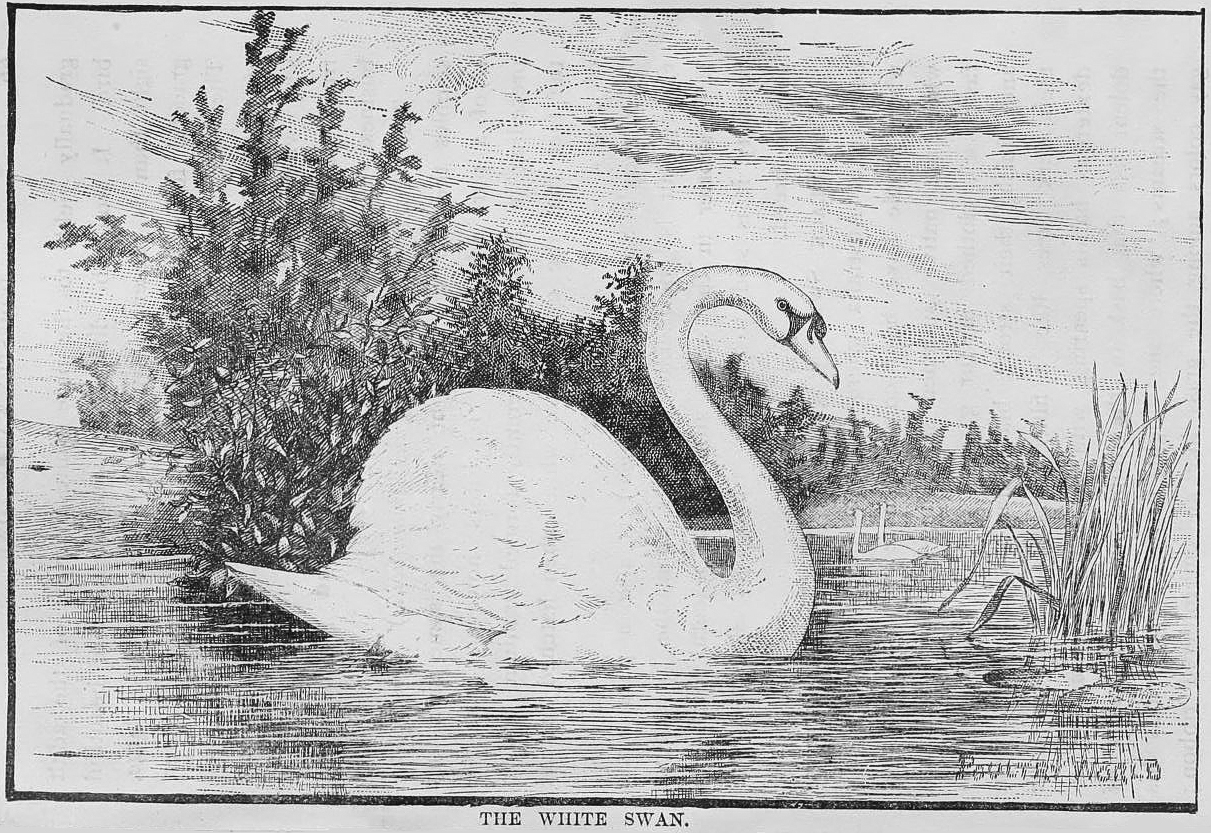

ALL varieties of swans possess the same general characteristics, the long slender neck, the large body that sits gracefully in the water, wide-spreading wings, and feet that send them through the water without apparent exertion. The swan has a wide habitat and is found in all but equatorial regions. In its habits the birds are migratory and fly, like the goose and duck, in a phalanx of two lines meeting at a point, something like a capital V laid upon its side. They seem to experience difficulty in rising, striking the water downwards with feet and wings and going half flying and half swimming for a considerable distance, before they take the air. But once on the wing, the birds rise to a great height, sometimes attaining several thousand feet above the earth. The swan, generally if not invariably, both rises from and descends to the water. Swans are monogamous, and the union once effected endures for life. Exceptions to this have been noticed, two females having been observed to mate with one male, but these exceptions are extremely rare, and but serve to "prove the rule." In their married life they present an example worthy of imitation by the human race. They display great affection, an extreme fondness for each other's society, swimming together and caressing one another with beaks and necks. In case of attack they will defend each other with courage and daring. They unite in the labor of nest building, the male gathering the greater part of the materials, the female being the principal builder. A swan's nest is no small affair, built up with coarse materials and lined with finer grasses, into the construction of which a great mass of materials enters. In the care of the young the male bird does his full share of duty, and equally with the female watches over, attends and protects the cygnets until sufficiently grown to provide for themselves. The egg of a swan is very large, and usually of a dirty white or pale green color. It is enclosed in a thick heavy shell, to prevent breakage from the great weight of the birds when incubation begins. From six to nine eggs are usually laid and then the female sits, the period of incubation being variously stated from thirty-five to forty-two days, the former probably being correct. When sitting it is not only useless but dangerous to disturb swans. Their wings are powerful enough to break at a single blow a man's arm, and at incubation they seem more pugnacious and intolerant of the presence and interference of man than at other times. Throwing meal upon the water is recommended as a good method of feeding the young. The old birds, when they have plenty of water range, need little or no feeding, except in severe weather, when grain may be given to them. Swans live to a ripe old age. "The century-living crow" that Bryant sings about, is but a puny upstart compared with the swan, if Willoughby is correct in fixing the limit to their lives at three hundred years. We may reasonably doubt this, but we cannot doubt that they reach a good old age. Probably a hundred years as the life-time of a swan would be within the limits of truth. One, even at such figures, wouldn't need to renew his stock very often. His first purchase of cygnets, barring accidents, would last him as long as he desired to breed swans, and be a pretty start for his children or grandchildren in the business. The natural food of the swan is chiefly vegetable, although an occasional fish and the spawn of many fishes come not amiss. Mr. Francis Francis has computed that at the lowest rate two hundred swans will, in two weeks, consume one hundred and forty millions of fish eggs. While, therefore, a trout pond might be an admirable place for swans, swans would not prove desirable assistants in rearing trout. The male swan is called a "cob" and the female a "pen." The males care but little for the society of the females except their own mates, and less for that of other males. They have no stag parties. But the females are gregariously inclined and like to flock together, like ladies at a tea-table, perhaps talking over the latest fashion and society notes in the swan world. The swan as yet is but an imperfectly domesticated bird. It retains many wild habits and instincts, although many of the birds are tame enough to eat almost out of the hand. By hatching the eggs under a goose, and by more care in bringing up the young, it is possible that the bird might be rendered more domestic in its habits, and with this might come a greater prolificacy, the six to nine eggs being multiplied into fifty or sixty, as is the case with the goose. If such a result should follow, the young, being hardy and easily raised, might become a market product, as their flesh is said to be excellent. The day may come when roast swan will be almost as common as roast turkey and may grace many a Thanksgiving feast or Christmas festivity, when severed families are reunited and domestic joys renewed. The Mute Swan (Cygnus olor) is the largest, most beautiful and majestic of all the varieties. In length it sometimes is fully five feet, and the expanse of its wings is remarkable. Its plumage is of a vestal whiteness; the bill is red, with a large black protuberance at the base; the eye is of a soft brown hue; and the legs and feet are of a brownish or blackish-gray color. Its name is misleading as the bird is not mute but has a soft and low voice tinged with melancholy, as if it had known a lingering sorrow too deep for words. Its long neck is gracefully arched as it floats upon the surface of a still lake, like a living gondola, and brings to mind a dream of Venice. "A dream of Venice brought to our own doors, With all the romance of its early days, Its doges and the marriage with the sea; We list for dip of some lorn lover's oars, Or song of gondolier borne through the haze, To make the dream a bright reality." It flies with almost incredible rapidity, a hundred miles or more an hour. The cygnets when first hatched, and for a considerable period of time, are clad in gray, which gradually yields to the pure white plumage of the ' adult bird. It would be difficult to imagine a more beautiful sight than is presented by a half dozen of these large, graceful fowls swimming upon a quiet expanse of water. They are the fit accompaniment of refined taste that often transforms a rugged farm into a beautiful country seat where wealth and culture find a temporary home from the hurry and worry, the drive and push of city business life.

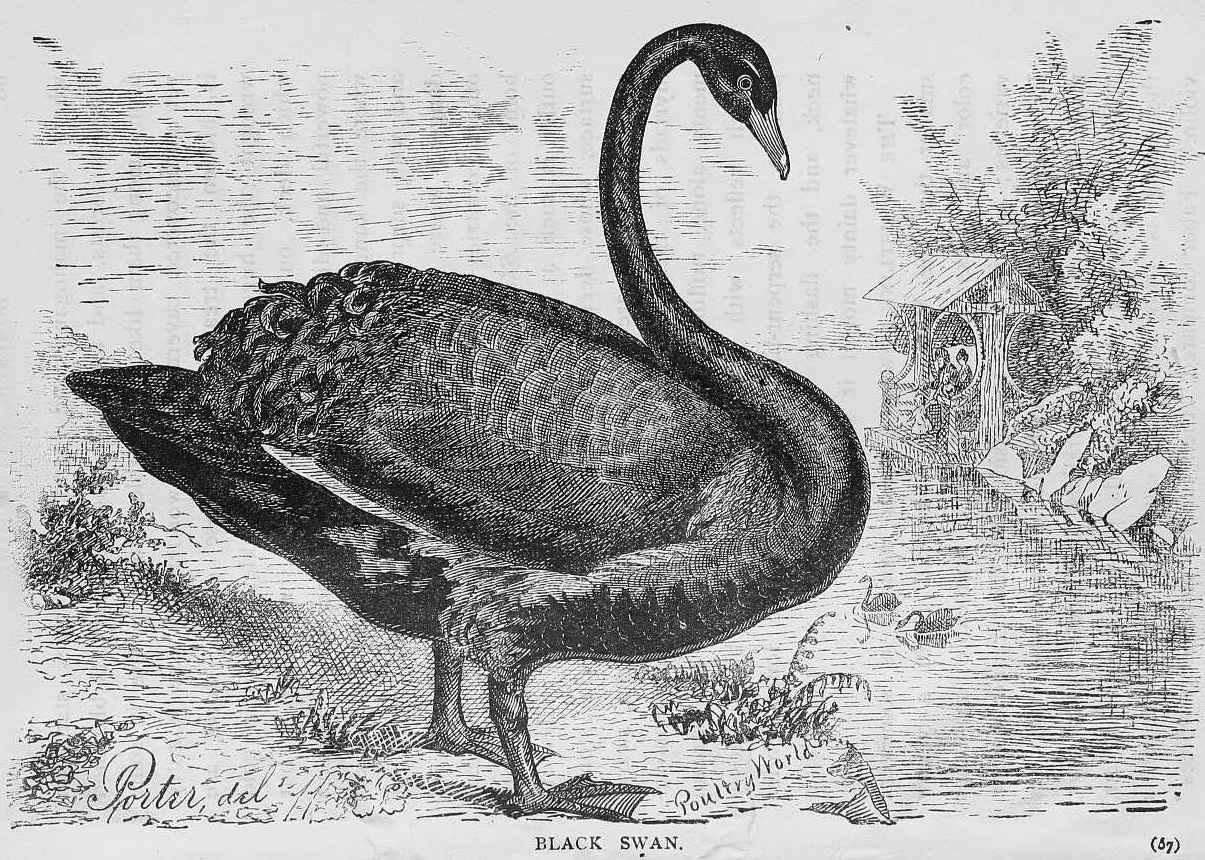

The Polish Swan (Cygnus immutabilis) closely resembles the Mute. It is of nearly the same size, and is of a pure white color. It differs, however, from the preceding in having a differently formed cranium, and in the fact that the cygnets are white when hatched instead cf gray. Bewick's Swan (Cygnus minor) is also a pure white variety, but is considerably smaller than the preceding. It is shorter in the neck, although a graceful bird. In captivity it is said to be very timid and shy, and unable to breed. The Black Swan (Cygnus niger). In that strange country of Australia where many of the most respectable white people have been convicts more or less criminal; where the native bushmen still cling to their mountain fastnesses, clothed in fur garments of exquisite softness and finish, their strong black hair standing out from their dark faces like a filmy chevaux-de-frise, and their dexterous hands spearing, with an unerring aim, the indolent fish that bask in the limpid and tepid waters of the streams; where the bright carpet snake winds his gay colors among the grass like an embroidered ribbon; where the mahogany and sandal-wood trees stand in limitless forests, and the white-tuad tree rears its blanched form among them like a vegetable ghost; where in some yet undiscovered cavern of the wonderful Vasse country is hidden the treasure from whose golden stores are wrought the huge bracelets and anklets of virgin gold which deck, on festal occasions, the simple-hearted but powerful and discreet natives of that inaccessible region; where the kangaroo slips his little ones into his pocket and with surprising leaps carries them beyond reach of danger; where all is strange and unique and unlike all other countries — there, and there alone, is the original home of the Black Swan. On the Swan River, whose outlet is such a sheltered bay that no wind ruffles its surface, whose deep waters are so clear that the stones and white sands are distinctly seen at the bottom, swarm myriads of these graceful creatures, their gliding movements, alone, ruffling the glassy surface of the stream which reflects with startling fidelity the black glossy plumage, the serpent-like movement of the long slender neck, and the flashing eye that detects at any depth whatever dainty morsel it seeks. The Whistling Swan (Cygnus musicus) is somewhat smaller than the Mute variety; its bill is of a yellow color and lacks the protuberance noticeable on other varieties; and its neck is considerably shorter and thicker. Its voice is its most remarkable characteristic, and has made it the favorite of naturalists and poets. Olaf says, "When a company of these birds passes through the air, their song is truly delightful, equal to the notes of a violin." Faber compared "their tuneful melancholy voices" to the sound of "trumpets heard at a distance." This swan, indeed, has been called "The Trumpeter Swan." Another has said that "the voice of a Singing Swan has a more silvery tone than that of any other creature." Schilling describes their voices as sometimes like " the sound of a bell and sometimes that of some wind instrument; still it was not exactly like either of them, just as a living voice cannot be imitated by dead metal." It is said, whether it be an amiable fiction or a veritable fact, that the death song of the swan is the loudest, sweetest and most prolonged which it ever sings. The poets have made use of this statement to add a charm and meaning to their verses' that we should otherwise miss. It will not pay to inquire too curiously into the fact; if it be false we do not wish to know it, and if it be true our enjoyment will be no greater than it now is. Shakespeare has been called "The Swan of Avon," and in "The Merchant of Venice" thus alludes to the death song of the bird, "Makes a swan-like end, Fading in music." And Byron sang, "Place me on Sunium's marbled steep. Where nothing, save the waves and I, May hear our mutual murmurs sweep; There, swan-like, let me sing and die." And Tennyson thus pictures the death of the swan: "The wild Swan's death-hymn took the soul Of that wild place with joy Hidden in sorrow; at first to the ear The warble was low, and full, and clear. And floating about the under sky. Prevailing in weakness, the coronach stole, Sometimes afar and sometimes anear; But anon her awful jubilant voice, With a music strange and manifold, Flowed lorth on a carol free and bold."

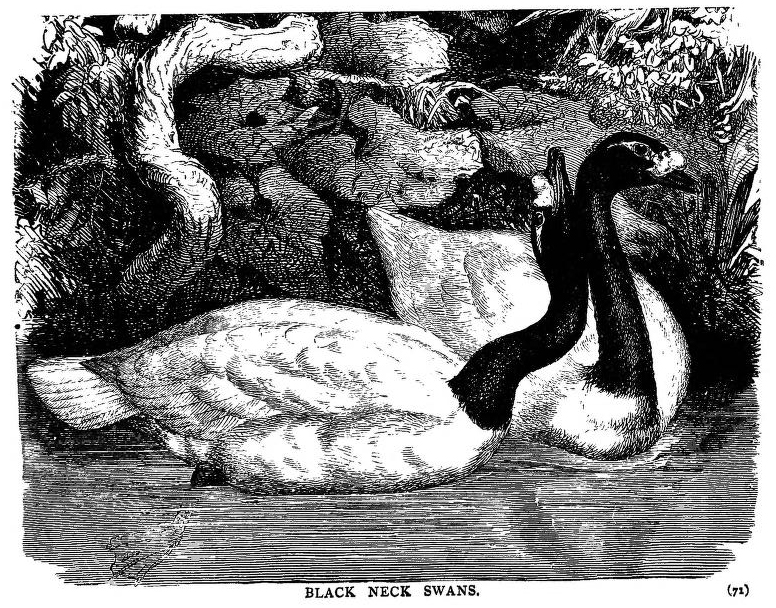

To the one who has seen these graceful water fowl, like Irving galleys, floating upon the surface of a limpid lake, it is not a matter of surprise that poets should be fascinated with them and that they should furnish the imagery of verse. No one is surprised that Milton should sing, "The swan with arched neck Between her white wings mantling, proudly rows Her state with oary feet." No one who is at all acquainted with that lover and interpreter of Nature, Wordsworth, is surprised that he should find the swan worthy a place in his contemplative verse, as in "Yarrow Unvisited " he exclaims, "Let beeves and home-bred kin? partake The sweets of Burn-mill meadow; The swan on still St. Mary's Lake Float double, swan and shadow !" But we need not cross the ocean to find a poet to describe the swan. Our own Percival in his poem "To Seneca Lake" thus sings: "On thy fair bosom, silver lake. The wild swan spreads his snowy sail, And round his heart the ripples break, As down he bears before the gale." The Black-Necked Swan (Cygnus nigrtcollis), also called the Chilian Swan, is a native of South America.

It has brown eyes; a lead-colored bill, with a large red protuberance at its base; and reddish orange legs. The head and neck, with the exception of a narrow streak of white across the eye, are jet black in color. The rest of the plumage is of a spotless white. It does not curve its neck, like other swans, in swimming, but holds it rather straight, like a goose. It breeds well in confinement, and the young grow with great rapidity, a circumstance not to be overlooked should swans be bred for the table. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD