Domestic Water Fowl

By H. H. Stoddard

Chapter 2

Geese

|

WE now devote a portion of this volume to the subject of rearing and keeping geese upon the poultry-farm, or otherwise; and this well-known and greatly esteemed representative of the feathered race is an important item, in an economic view, in the yearly aggregated value of our poultry product in the United States. Probably in no country in the world do there exist greater facilities, in various ways, for the profitable raising of geese than those easily accessible to our farmers and country people in various sections of this land. Certain is it, too, when the surroundings are appropriate, and the land upon which geese may be reared is not suitable or valuable for other rural or agricultural purposes, that this grand bird is one of the most profitable that can be cultivated, for various reasons. And yet it is a fact that but few American poulterers appreciate the goose at its fair value. And taking the breeders of poultry together, as a mass, there is but a small minority who care to attempt geese-culture anyway, or to any considerable extent. The poorest of poor pasture-ground will suffice for their grazing. Swamp, marsh, stream or river suits them equally well, for bathing, feeding and sporting in the water. And between land and water they will contrive to forage largely for their sustenance, if they have room enough — thus reducing the cost of their keeping for most of the year to a merely nominal sum. Of all known poultry-stock, geese are in the main the most profitable fowl that can be reared, where the situation is such as is appropriate and convenient on which to breed them — and the land they occupy for range is not needed or suited to other farming purposes. There are thousands of old farms and estates along the American sea-coast, as well as in the interior, whereon geese could well be kept and reared to profit — which lands are useful for little else. And as we have heretofore suggested, we repeat that those who own such otherwise useless and uncultivated property, on which there are the requisite "water privileges" we have referred to, will do well to bear this hint in mind. The experiment, at least, will cost but little, and with intelligent management, we are confident that success will follow upon this undertaking, in almost any. location where geese are raised in quantities within reasonable distance of a good market. The breeding of geese is a very simple process, where the farmer or poulterer has the proper surroundings and facilities on his place to grow them. But water is a prime necessity for their accommodation; and without this — in the shape of marsh, run, pond, swamp or sea-shore estuary — geese cannot be reared to advantage, of course, in any quantity. Other kinds of poultry are good in their way. But there is no portion of the goose that is not good for something. The liver is a choice tid-bit, as every lover of the pate de foie gras very well knows. The feathers are valuable, and they yield these when dead or alive, in considerable quantity. Their plumes make admirable quill pens. When fatted, their meat is a most desirable dish in cold weather for the table of the bon vivant. And while living, if kept upon a private pond or miniature lake, they are next in beauty to the admired swan, as an ornamental water fowl, upon the premises' of the well-to-do farmer or country gentleman. Why not breed geese then? The reasons given generally are because they are supposed to be enormous eaters, and because the method for raising them successfully is not understood. But as a matter of fact, neither are they expensive to feed or difficult to rear ! Anybody who can set a hen, and who is able to care properly for a brood of chickens, may raise a flock of goslings — provided the birds have water at hand for their accommodation, when it is needed for them. Usually a gander to three or four geese will be found sufficient. But they will breed better in pairs than otherwise, as the male of this breed (like the cockpigeon), when the female is sitting, guards the nest while the goose is away feeding, daily. The gander is at his best for service after his third year, and he will last many seasons in full vigor. As layers, geese are at first inconstant. After they are more mature, they will lay pretty regularly, and will yield a litter of fifteen to eighteen eggs before inclining to be broody. But all depends upon the weather, and the season of the year. Occasionally old geese will lay in a year as many as sixty to seventy eggs, but this is not of common occurrence. The average number is forty-five, or less. If they can have plenty of water and pasture ground to roam in, geese will thrive and grow, without getting fat, if they have little or no feed besides. When the goose is ready to lay, you will notice that she carries straw, sedge or stubble in her bill to make a nest with. Confine her in a shed-roofed box, and she will shortly show her eggs. In the same nest where she deposits her first egg, usually, she will lay out her litter of fifteen to twenty eggs. When broody, she will remain upon her nest, after laying. Give her a deep, oval nest to sit in, and let her have thirteen to fifteen eggs to sit upon. She will bring forth her brood in twenty-eight to thirty days (according to the warmth of the season), and if left alone and undisturbed by the rest of the flock, or by other interference, the mother will almost invariably take good care of her goslings from the outset. While incubating, the goose should be well fed. If left to gather her own sustenance, she will frequently remain away from her eggs too long, and allow them to chill in cold weather. Food and water near by, within the house where she sits, will obviate this. Like newly-hatched chickens, the young goslings do not need food for twenty-four hours after hatching. Then give them stale bread, scalded bran and potatoes, milk curds, dry boiled green stuff and hard-cooked eggs for a week. Keep them away from the water for two weeks — and house them, dry and warm, until they get strong on their legs. The goslings may be allowed to follow the mother to the open water when fifteen days old, with safety. Previous to this time, their down is not a sufficient protection against the chilling effects produced by their earlier indulgence in the swimming bath. From this time forward the young must be regularly housed at night, and fed for some weeks steadily with soft food of meal and vegetables at morning and evening. They will, under this treatment, grow smartly, and soon learn to become active foragers and grazers, like their parents. Rats will devour young goslings, if they have an opportunity, and chance to be plentiful in numbers in the immediate neighborhood of the goose-pens. But they do not trouble the geese. The fox is the most dreaded enemy to the goose-keeper. But his depredations are limited in great part to the night time. It therefore becomes a point of consequence to goose growers to make sure that the houses in which geese are sheltered at night are fastened up and are fox-proof. The weasel, the skunk, the muskrat and the mink will assail geese also. And where a large flock is cultivated they will attract these night vermin to their quarters from a long distance, frequently. Care should be had, therefore, to make the house a protective shelter against the probable or possible incursion of these marauders. The building where the geese lay and sit, and where previously they resort at night to roost, may be a plain board or plank lean-to shed, six feet high in front, and running back to four feet high, for walls. Shingle or batten this tightly. And when the young ones are hatched out, care should be taken that the floor is Kept dry for two or three weeks, lest they take cold and die off before they are two weeks old.

The floor of the house should be kept clean, also, when the young goslings are about. And for a month after the hatching, it is best to confine the mother and young by themselves. The little ones need to be better fed than the old birds, and consequently (until they go to the water) they should have a small pen away from the main flock to dwell in exclusively, with the mother-goose. Geese are hardy under ordinary fair treatment. There is very little sickness among them, usually, and they live to a ripe old age, if permitted to do so. But commonly it is desirable to slaughter and market this race during the first year of their lives. A yearling goose (or gander) is at its best for eating at ten to twelve months old. They should have good foraging ground from the beginning, and it is better with these (as with turkeys) intended for marketing that they should in some way be well fed always, from goslinghood to early winter time. Then they may be quickly fattened, when put up at last. The flesh of geese is very desirable eating, but they must be fattened and slaughtered at Christmas or New Year's to render them the most salable. Old geese are not toothsome, ordinarily. For fattening, the best corn meal and potatoes boiled together are as good a kind of food as can be given them. They should have all they will eat of this three times a day, just before killing. And in a brief space of time they will be in readiness for the butcher and a market, where they will command a good price, among seasonable dead poultry.

During the summer and fall they will resort to the pasture-pond, or stream, and obtain green and other desirable provender, to their satisfaction. At night, when they return to the houses, give them a dish of mush, or a supply of sound whole corn. This will keep them till morning. Then furnish the early meal, and set them at liberty for the day. In this way, systematically managed, geese may be raised by any one, with but slight experience even, to his satisfaction and pecuniary profit, upon premises where the stock may be able to gather a goodly portion of their daily food on the meadows or streams adjacent to their coops or houses, which are best built near the margin of the water they daily visit, for feeding and pasture. The feathers of an adult goose will weigh about a pound and a quarter annually. Some persons pluck them twice, some thrice in a year, and obtain five, six or eight ounces at a time. Inasmuch as there exists no extraordinary difficulty in raising geese, since at maturity these splendid water fowls are salable at a remunerative price, when fattened and slaughtered; and when it is considered how valuable are their feathers, it certainly seems that much greater numbers might be bred in this country, to advantage, than our poultrymen and farmers hitherto deemed it advisable to produce. The demand for geese will increase as this article of food becomes appreciated.

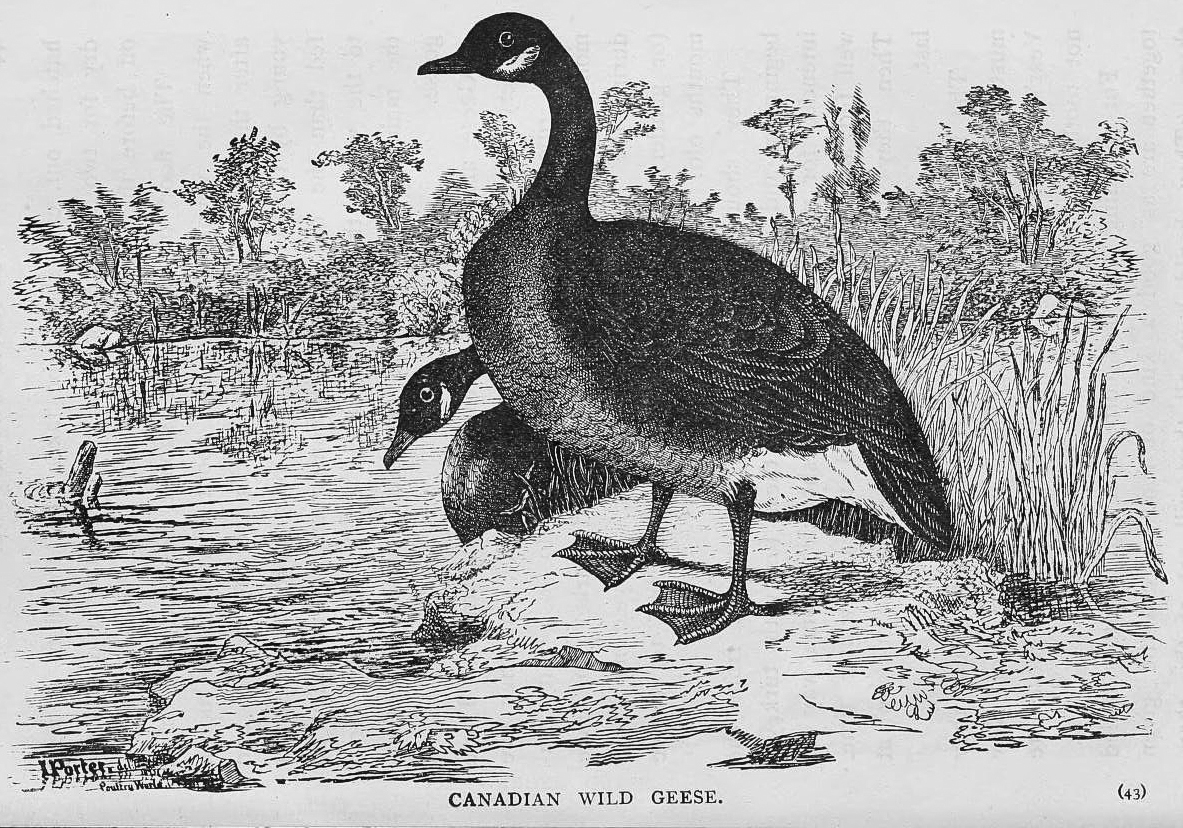

The most popularly bred of all varieties of the goose are the common or mongrel gray and white sorts. These are, generally speaking, descendants from the original Gray Lag Goose, and may be found widely disseminated in small flocks in every portion of this country, especially in New England and throughout the Northern States, being cultivated for the nearest city markets, where thousands are sold annually for consumption. Long domestication has increased the size of these geese. And in many districts where attention has been and is given to selecting the best and largest ganders every year to breed to the better class of females, fine yearlings are produced by poulterers who understand this branch of their business, and who keep their geese upon the right kind of land — as a specialty. In addition to this mongrel race, we have also the superior White Embden or Bremen variety, the great Toulouse, the mammoth Hong-Kong or African, the Egyptian, the small Brown China Goose, the White China Goose, the Canada Goose, and the Sebastopol — a new variety, but little known. The three principal sorts now named — to wit, the Bremen, the Toulouse and the great Hong-Kong, are but sparsely bred among us, compared with the number of common geese grown annually in America. But the introduction of ganders of either of these breeds among the flocks of common geese, has had the same effect in increasing the size of the progeny (in the first crossing) that the mammoth Bronze cock has occasioned by his admixture with the common race of hen-turkeys around us. which is called in Europe, technically, the " Canadian " or Canada Goose, is very well known throughout this country; and dead specimens are frequently seen in our city markets in the fall or winter every season. These are shot "on the wing," as they pass in their migrations in myriads over the prairies and along the sea-coast — from their breeding places in the far North to more genial southerly climes, whither they migrate annually.

Many attempts have been made, where ganders of -this tribe have been occasionally secured alive, to breed this bird as a cross with the common goose. But the experiments have not proven often very successful. The nature of the Wild Goose is not favorable to this mixture. Audubon, the ornithologist, kept a few, but could not in three years trial induce the old birds to breed in confinement. He took a few young ones, which he secured at the same time, and these bred indifferently. In other instances, where wounded Wild Geese have been captured, and bred to the common breeds afterward, it is recorded that young have been hatched from the union. These goslings were mules, however, and they were not productive. Although it has been claimed by a few persons who have bred the Wild Goose among their domesticated flocks that the progeny of their connection has been as profitable as the others, and that the half-bloods show superiority in size, we are satisfied from abundant contra testimony that this union is not a practical thing, as a rule, even if it were not an exceedingly difficult thing to procure the Wild Gander in a fit condition to breed him to our domestic geese. And so we opine that the better method is to make use of the varieties which may at all times be readily obtained, and which, when grown together or among the mongrel race, will yield the larger product, with a much lessened degree of cost and trouble.

THE COMMON DOMESTIC GEESEare too well known to require at our hands any elaborate description. They are grown everywhere and anywhere, in small or large flocks, where the commonest facilities are at hand, or where any kind of feathered biped can subsist. But the better the care and conveniences afforded them, the better the results to their keepers, as a matter of course. All fowl-stock thrives when well attended to. The common geese, either white, gray or mottled, are, in proportion to the whole number bred in this country, at least a thousand to one. The large varieties we have mentioned are comparatively but seldom seen on our farms; and either the Bremen, the Toulouse or the African are to be found, in their purity, in possession of but few fanciers — who grow the latter for breeding stock or as ornamental water fowl, for the most part. In view of the incontrovertible fact, however, that the bulkier varieties, at the same age, may be grown just as easily and with as little trouble or care as the others it is surprising that those who cultivate this race at all do not choose the heavier and larger sort in preference to rearing the mongrels! An ordinary eight or ten-pound "green goose " at Christmas-time will command for price as dead poultry in market from a dollar and a half to two dollars cash — according to weight and quality — and these are produced by the thousand every year, among the common race. At nine or ten months old, a well-fed specimen, of the larger-bodied varieties will draw twelve to fourteen pounds (frequently more), and sell for two or three cents per pound higher than the best of the mongrels will bring. And the extra cost of bringing the more meaty fowl to this condition, at the age mentioned, is hardly perceptible.

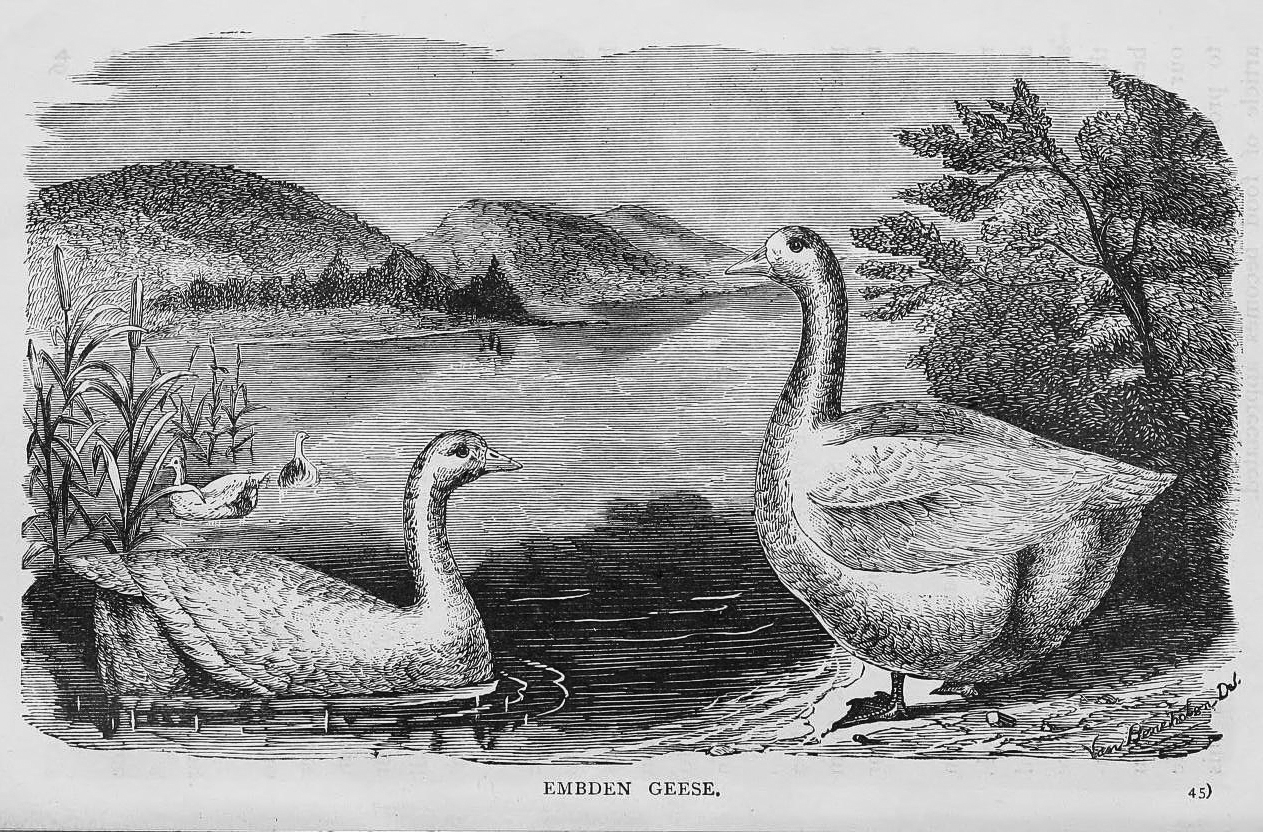

Why, therefore, shall we not cultivate the heavier sorts? The first cost for breeding-stock, it is true, is greater. But the rapidity with which this race is multiplied — where the proper facilities are at hand to grow geese — is a sufficient answer to this oft-repeated objection, to every sensible, enterprising poultryman. THE EMBDEN GOOSE is also extensively known as the White Bremen goose — the first that we ever had in America having come direct from the port of Bremen; Germany. These were imported by John Giles, of Providence, and by Col. Samuel Jaques, of Ten-Hills Farm, Medford, Mass., some sixty-five years ago. These geese are of mammoth proportions, as also the Toulouse; ganders of either breed frequently weighing twenty-eight to thirty-five pounds, each, alive. Mr. Sisson of Warren, R. I., a few years later than the other importers mentioned, received from Bremen a few of these splendid fowls, and wrote that "they lay early in March sit and hatch with much greater certainty than do the common geese, will draw nearly double the weight at same age, yield quite twice the quantity of feathers annually, never fly at all, and are uniformly of a snowy whiteness."

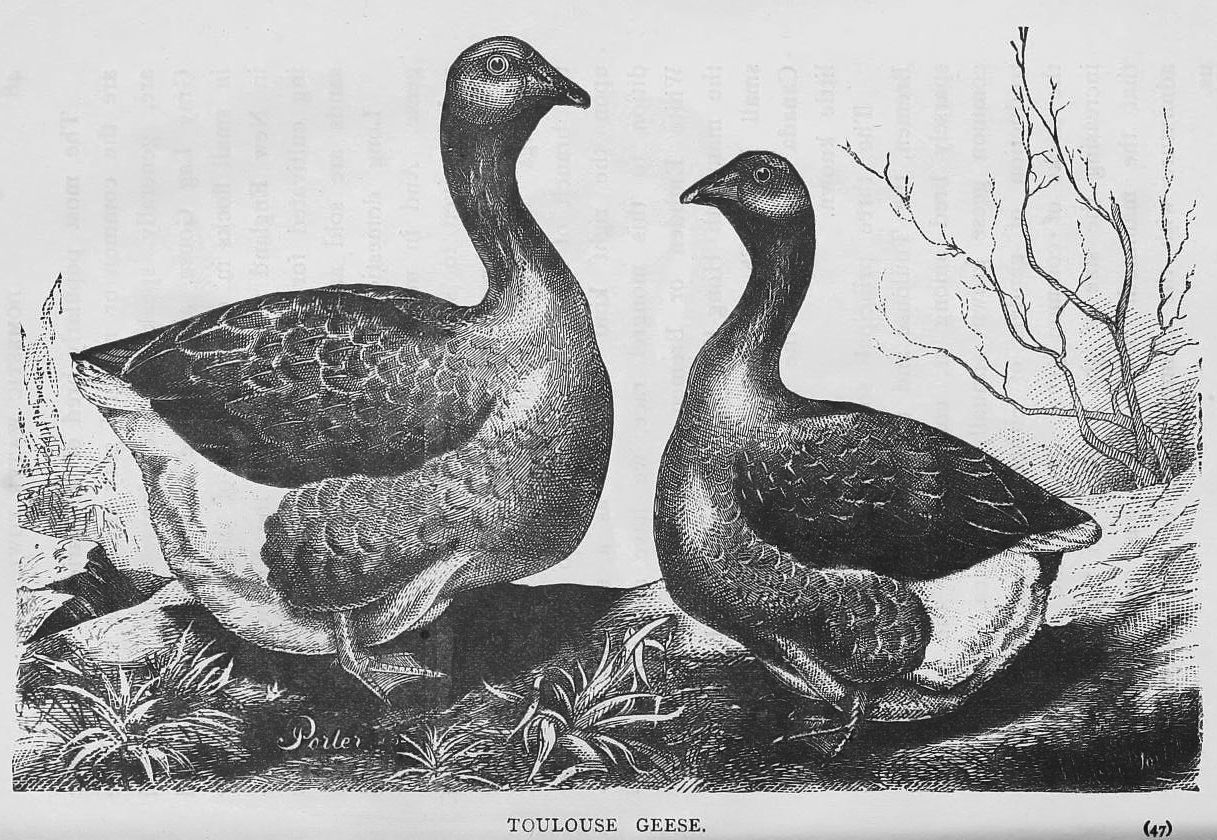

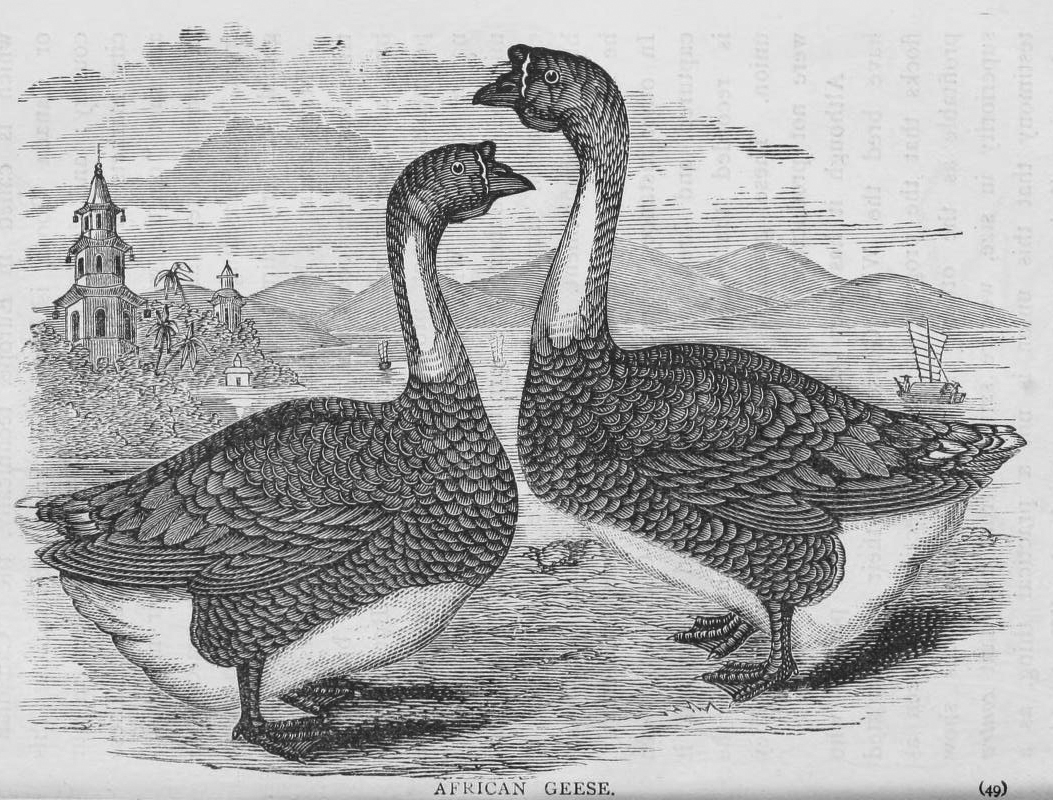

Within twenty-five years, the Bremens have been sold at $40.00 and $50.00 a pair, for breeding stock. Now they are more common, and can be had at $10.00 the pair, of fanciers in various parts of this country. Crossed with the common white goose, the progeny retain the original pure white color, and are enlarged greatly in size, at once. THE TOULOUSE GOOSE is also an enormous bird, but is thicker and shorter in form. Its color is brownish gray, all over, with lighter tinted plumage under the breast and belly. They grow very rapidly, from the shell, put on fat readily, and at maturity will equal the Bremen in weight, and frequently are known to excel the latter in this respect. These crossed upon the mongrel gray or brown goose, produce a progeny that are also increased in size largely — and which are a very salable article of poultry at about Christmas-time, and subsequently, in winter, annually. THE AFRICAN GOOSE averages the largest of all the varieties known to Americans. Pairs of the early importations of this variety into this country are publicly recorded to have weighed fifty-six pounds, for a gander and goose; and forty and fifty pounds per pair is not an uncommon weight to be attained at the present time, where these fowl are purely bred from original stock. We have had this breed (in limited quantities) in the United States for about thirty-five years.

The Hong Kong (or "African") goose is brown, in color not unlike that of the Toulouse. But his shape is entirely different, and he wears a large horny knob at the base of his upper mandible, which distinguishes him from the others — and which has in some places given him the name of the "Great Brown Knobbed Goose." So far as we are informed, this variety of geese lay but few eggs annually, in comparison with the yield by the Bremen and Toulouse. And this fact perhaps accounts for the scarcity among us of this really fine water fowl. But these three varieties are now thoroughly appre ciated in this country and in Europe. And whenever they have either of them been used to cross upon the common geese, they have unmistakably left their mark upon and vastly improved the progeny that has succeeded such crossing.

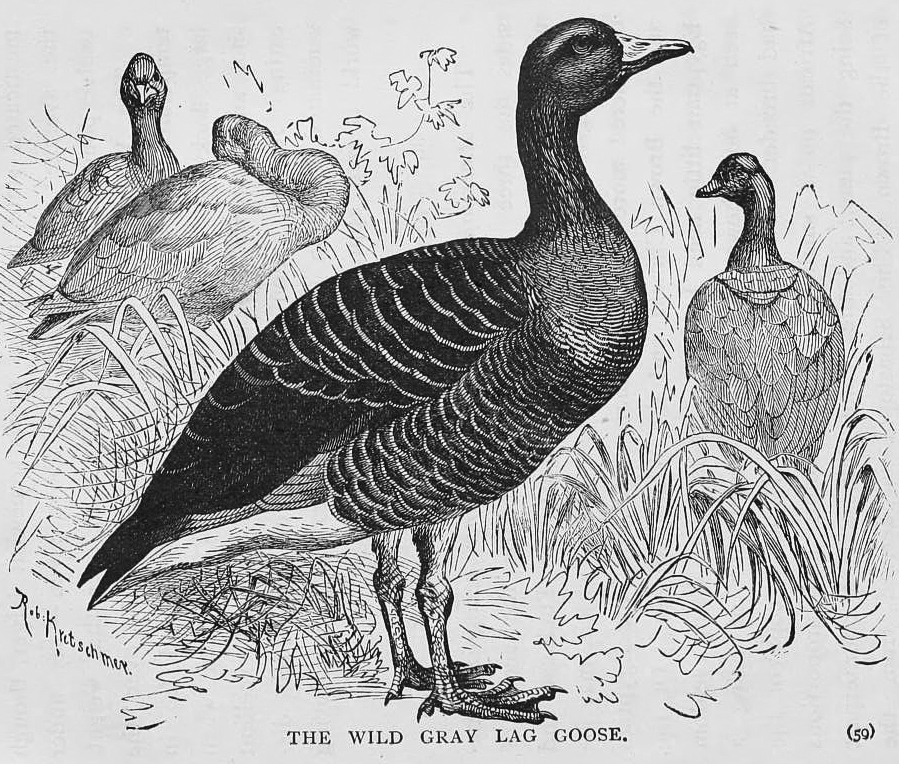

THE WILD GRAY LAG GOOSE. The cut on page 59 (above) is an accurate representation of the Gray Lag Goose (Anser ferus), claimed by the best, as well as the oldest authorities, to be the original of the race known to Europeans, and considered identical with the Common Gray Domesticated Goose, familiar the world over, to-day. The Gray Lag Goose is among the largest of the various wild species, in its native state. They will average ten to eleven pounds weight. The bill is flesh-colored, usually, tinged with yellow. They are grayish-brown in the plumage, the breast and belly whitish, graded with ash-color; the back and rump feathers white and yellowish-brown; and the feet flesh-colored, or pinkish. In its domesticated state, this goose grows somewhat larger, though the average size is about that above given — say under twelve pounds for yearlings, rather than over that weight. The Wild Gray Lag is well known all over the temperate portions of Europe. They go to and fro in large flocks, as do our Wild Canada Geese, and when shot and properly cooked are found to be most excellent eating. As the undoubted originator of our widely disseminated Common Goose, its value to the poultry-loving world is well appreciated.

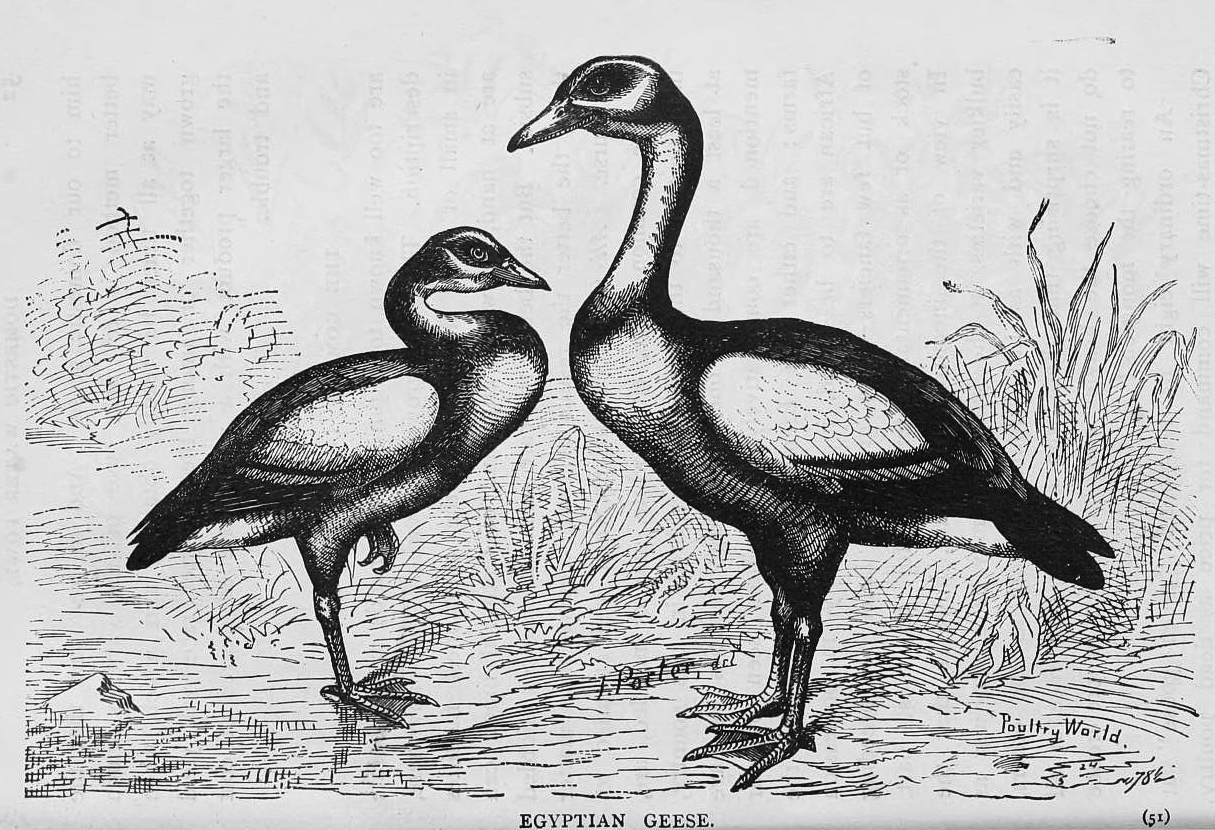

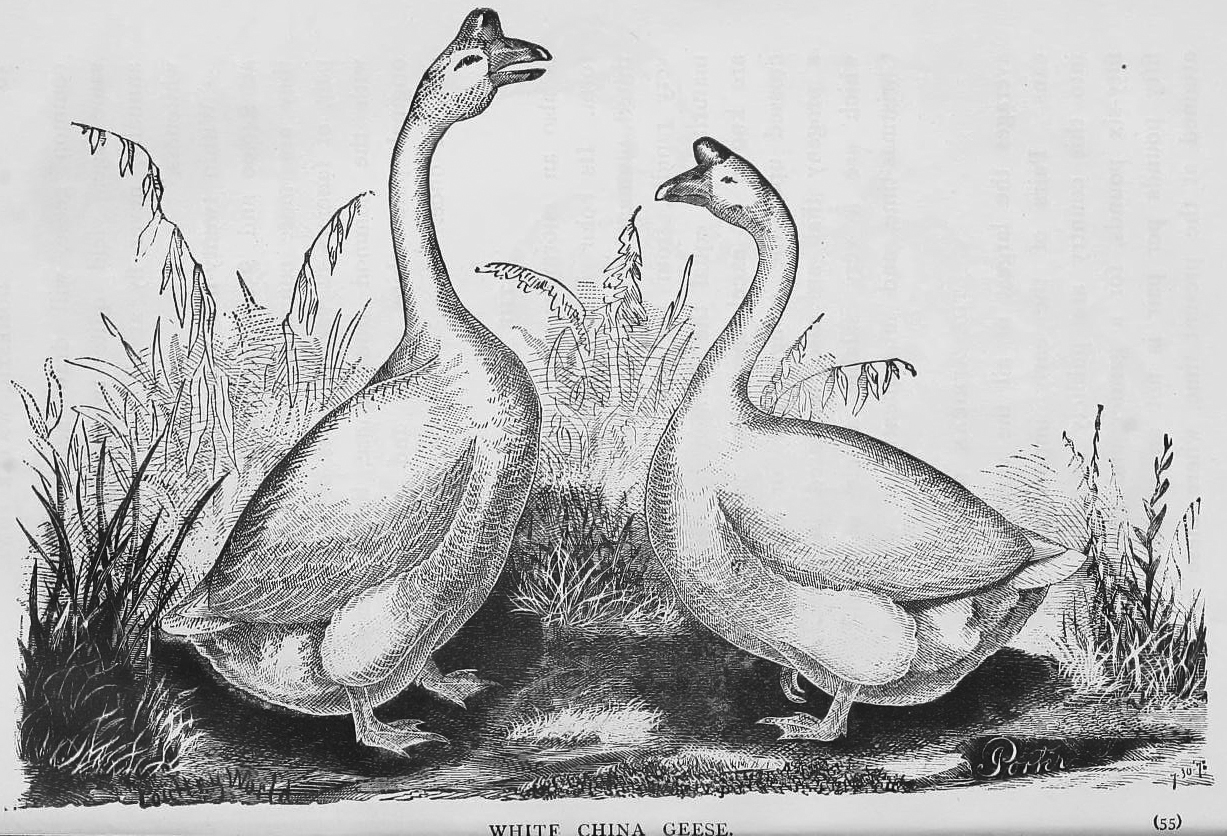

OTHER VARIETIES OF GEESE. The American Standard of Excellence recognizes, besides the three principal breeds noted on the score of utility; viz., the Embden (or Bremen), the Toulouse and the Hong-Kong (or African), three others, which may be considered more ornamental than useful, viz., the Egyptian and the Brown Chinese and the White Chinese. Of the Egyptian little need be said. It is rare, being seldom seen at our shows, and has the reputation of being a bad breeder. The Brown Chinese is but a copy of the African on a smaller scale, the colors and proportions being the same, and the White Chinese is a counterpart of the Brown. The Sebastopol is derived from the region from which it takes its name, and possesses the merit of oddity in plumage, which ' is its principal claim to attention, as will be seen in the cut. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD