Domestic Water Fowl

By H. H. Stoddard

Chapter 1

Ducks

|

THE breeding of ducks for market purposes pays well, where there are suitable facilities at hand for prosecuting it, for there is always a good demand for both the flesh and the eggs. Generally in winter and spring ducks sell considerably higher than chickens, pound for pound, and the price of duck eggs is often higher than that of the choicest hens' eggs. Under favorable conditions, ducks are splendid layers, and during the height of the laying season will average nearly an egg a day for the entire flock for several weeks, so that there is no question but that duck breeding will pay when conducted properly. Those who have not made a trial of this kind of poultry, and are situated to do it properly, should at least experiment in this direction. Ducks are, as a rule, freer from attacks of disease and disorders than any other breed of fowls, but they must have plenty of room and sufficient water. They do not do well in confinement, though they must, during the laying season, be confined in their pens until they have laid their eggs, else they will drop them around promiscuously, wherever the desire seizes them, and thus many will fall to the lot of crows and skunks and other marauders. They will generally lay by or before ten o'clock each morning, when they can be given their liberty for the remainder of the day. By giving them a generous supply of food each evening, the flock will be sure to come home promptly at eve, when they can be penned up until after they have shelled out their eggs next morning. A river or larger stream is objectionable rather than otherwise, and more success will be had by Restricting their water privileges to a small and good stream. We know of one breeder who annually rears two or three hundred ducks, who utilizes a stream not larger than would readily flow through a four-inch pipe; by damming up the stream here and there he secures basins for them to bathe in. The brackish water near the sea coast where small creeks empty affords an excellent feeding place for ducks. Fanny Field gives some very good hints, rules and opinions about ducks and ducklings in the Prairie Farmer, from which we extract the following: "Every farmer who has a pond or stream of water on his premises should keep a few pairs of ducks, at least. As a rule, where there is any market within a reasonable distance of the farm, ducks and ducklings may be •profitably reared. Young ducks, in good condition, always command a good price in city markets, their feathers sell at a good price, and the eggs for cooking, and a roast duck occasionally, make tempting additions to the farmer's table. A good many farmers, who live too far from market to render it profitable to raise ducks for sale, would find that it would pay to raise them for feathers, and for meat for their own tables. Where one is blessed with a family of children the entire charge of a flock of ducks might be given over to the little folks, and they would take an infinite amount of pleasure in caring for the ducklings, collecting the eggs, feeding the old ducks, and watching their antics in the water. And then your little folks would be learning something all the time, and take my word for it, that there is nothing so good for children as to give them something to care for — to have them feel a sense of responsibility. "For a small flock a rail pen may be constructed and covered with boards. Have one side higher than the other, so that the board roof will shed rain. I have a good-sized yard near the water, surrounded by a picket fence, and with a long, low shed across the north side. Nests are placed along the back side of the shed, and the floor is well covered with dry gravel and earth, which keeps the floor free from filth. This spring I intend to extend the fence, so as to inclose a portion of the stream, and put in water gates, so that there will always be plenty of water in the yards at all times. Of course, the ducks are only confined in the yard at night, but I find that in winter and during the cold rains of early spring and late fall they spend a good deal of the time under the shed. "As ducks frequently lay for two or three months before they take a notion to rear a family, it is necessary, especially when one wishes to raise a large number of ducks, to set some of the first laid eggs under hens. The directions given for preparing nests and setting hens must be attended to when setting a hen on ducks' eggs. Do not crowd the nest; five ducks' eggs are enough for a small hen, and seven or eight for a Brahma or Cochin. Unless the eggs are set on the. ground, particular 'attention must be paid to the sprinkling with tepid water during the last two weeks of incubation. Sprinkle slightly every day while the hen is off for food. Neglect this and your chances for ducklings will be greatly lessened. Ducks' eggs usually hatch well. With fresh eggs that have not been chilled, and have been carefully handled, you may count on ducklings at the rate of ninety for every hundred eggs set. I don't think it pays to hatch ducklings very early in. the season, unless one wishes to raise some extra large birds for exhibition. Ducklings grow rapidly, and if hatched in April and May will grow to a good size for the winter market. Feed young ducklings on the same things and in the same way 'that you would feed young chickens. Feed ducks as fowls are fed. "The proper time for picking ducks may be ascertained by catching two or three of your flock and pulling out a few feathers here and there; if they pull hard and the quills are filled with bloody fluid, the feathers are not 'ripe,' and must be left a while longer; but if they come out easily, and the quills are clear, the feathers are called 'ripe,' and the birds should be picked at once, or they will lose the greater part of their feathers. To pick a duck before the feathers are fully ripe is to injure the bird very much; you will find a bunch of very long, rather coarse feathers under each wing; do not pluck them, they support the wings. When picking take but few feathers at a time between the thumb and forefinger, and give a short, quick jerk downward." MALLARD DUCKS.

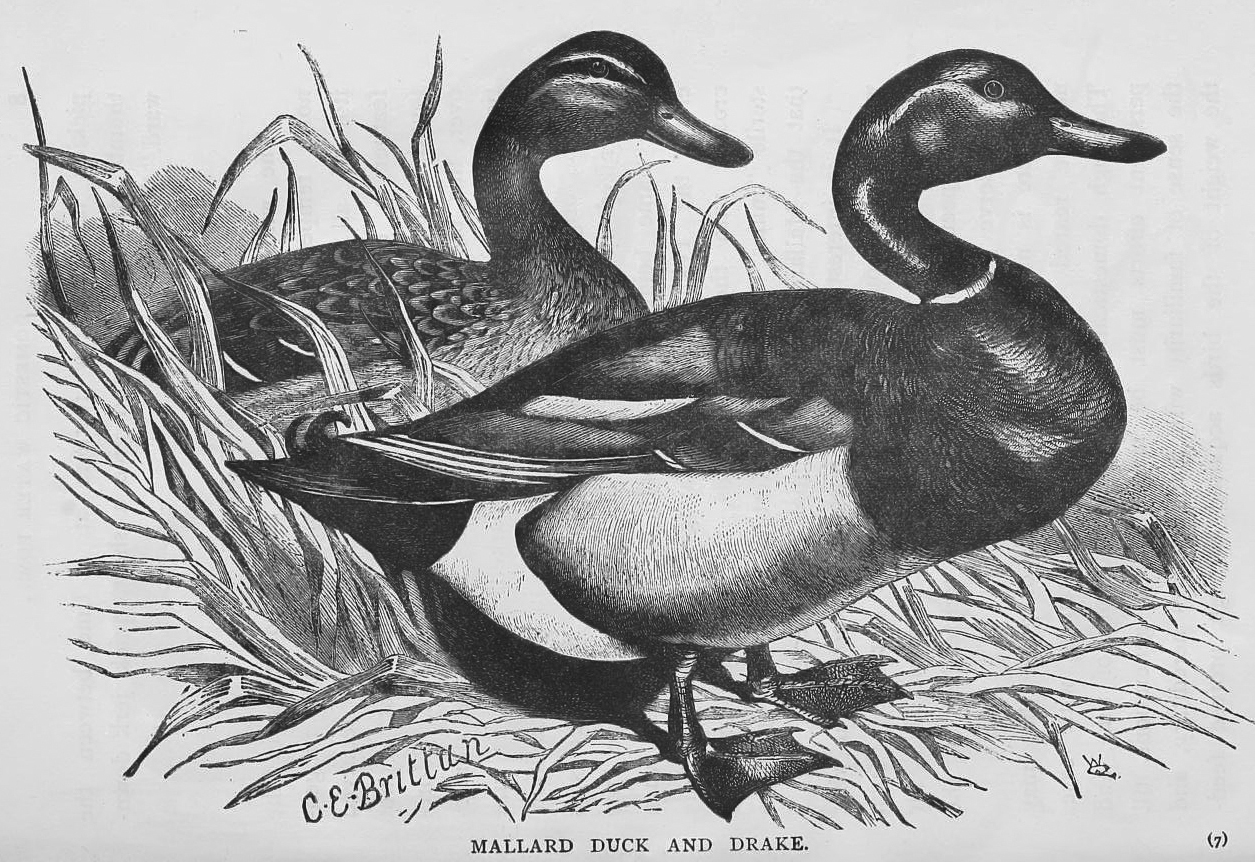

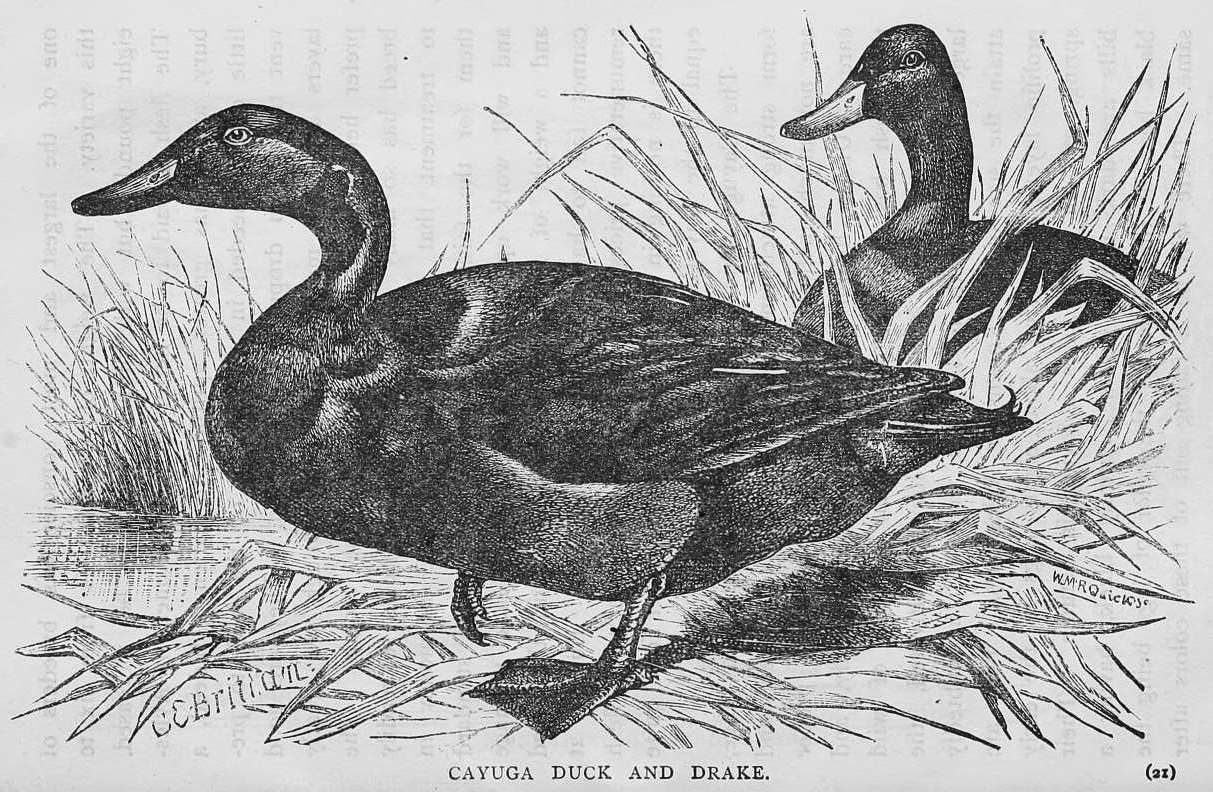

The wild Mallard is found in all countries in the north temperate zone, and is undoubtedly the progenitor of all our domestic breeds having the recurved feather in the tail of the drake, a feature that is not found in other wild varieties besides the Mallard. Moreover, this breed of wild ducks comes easily under domestication, and is susceptible of marked variation in size and color when for a few generations in that condition. The origin of the domestic from this wild species is recognized in several of the languages of Europe, the same name being given to both. Besides this, when either the Pekins, Rouens, Cayugas, or Aylesburys are crossed with the wild Mallards, the offspring are not sterile "mules," but perfectly fertile, which fact indicates that the Mallards are the original wild species. It is interesting to many persons to know from what wild species our domestic fowls were derived. Such evidence as we have advanced is the most reliable, for certain peculiarities, as the recurved tail-feather of the drake, serve as a brand for ages. There is no species of wild duck or goose that may not be reared in captivity and half-tamed with ease. Thorough domestication is, however, a work of time, and persistent efforts must be made through generations, till the sense of familiarity with man becomes hereditary, and the weight of the birds acquired through profuse feeding, and the weakness of wing caused by disuse, make them incapable of prolonged flight. There is much uncertainty and obscurity in the genealogy of even man, the writer of history. But there is strong evidence that even the most civilized people had ancestors in a "wild state;" forefathers that would not, if pictured, excite ancestral pride. So in the case of animals we only mention indications. The history of the origin, not only of nearly all the various species of our domestic animals, but also of most varieties into which th.y are divided, is extremely obscure, or wanting altogether. The origin of the ROUEN DUCK,

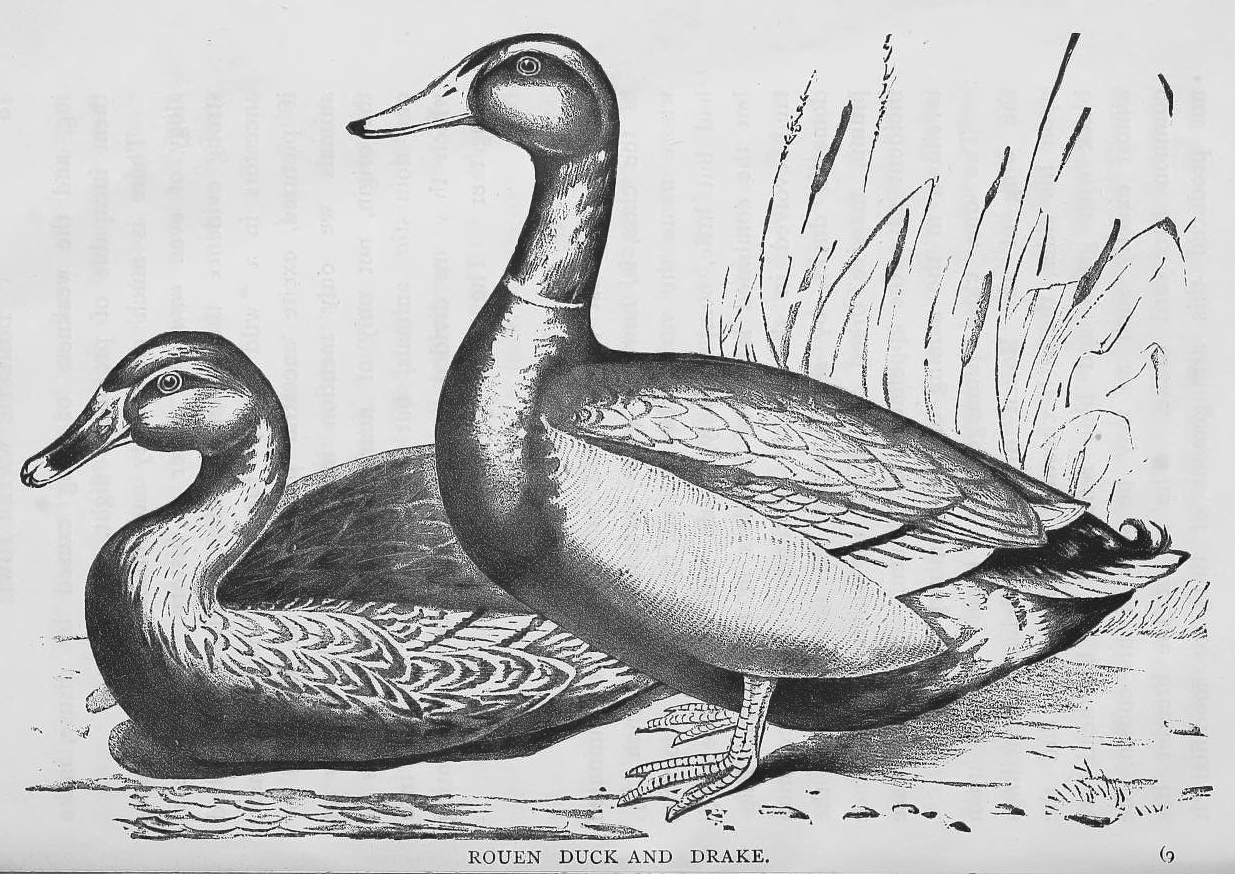

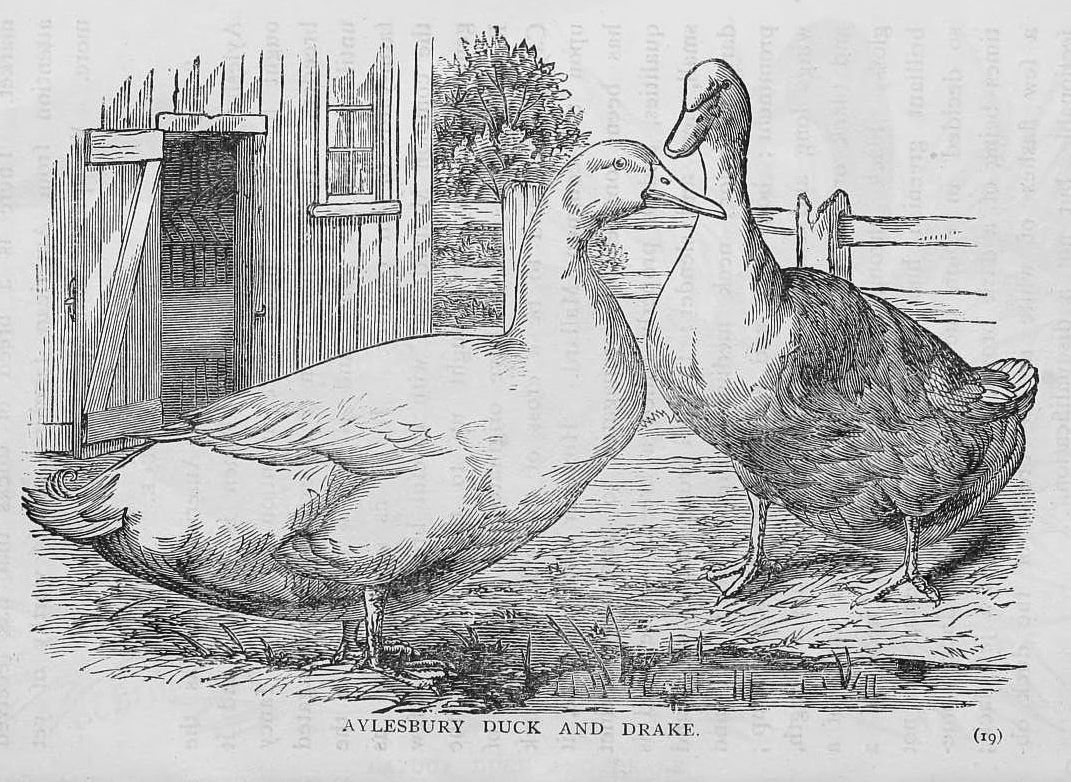

one of the most valuable and most widely disseminated of the class, is, however, quite certain. The French city, whose name the variety bears, and the district adjoining, had but little, comparatively, to do with its "make up;" but the combined labors of breeders in France and England evolved in the process of time, from the common domestic ducks, by selection on the basis of size, the plump, massive breed or variety to which some chance incident gave the appellation of Rouen. A parallel case is shown in the naming of the Hamburg fowl. The fine, close plumage, the " beauty spots " upon the wing of the Rouen drake, the delicate penciling upon his sides, the rich chestnut of his breast, and the black with green and blue reflections of his head, are almost exactly such as may be seen in his cousin, the common barn-yard drake. The art of the breeder has not produced this arrangement of tints, or modified it essentially. The Rouen inherited it from the common domestic stock, who in turn derived it from their wild ancestors, the free, untamed denizens of stream, lake and fen, over the whole of the temperate regions, and a part of the tropical and arctic, throughout the entire northern hemisphere. The body of the Rouen is larger than that of the common duck, some specimens attaining great weight. Some pairs have been exhibited weighing thirty pounds. Thus we see how lightness of body and gracefulness of the wild species has been changed, owing to the influence of domestication, the effects of plentiful feed and easy life. The wild bird has a habit of activity and takes long flights, and has comparatively light weight, without much variation. The Rouen drake has lustrous green plumage on head and neck, the lower part of the latter having a distinct white ring, but not quite uniting at the back. The breast is dark, or purplish-brown, and the wings show colors of brown, purple and green, which do not fail to excite the admiration of the beholder. The duck has a less gorgeous dress of brown, penciled with darker brown, the wings having bars of purple, edged with white. Both sexes generally breed true to color. Probably the exact similarity of plumage, which has been preserved during improvement in size, like that of the common and wild varieties, is the result of man's selection. There was a beautiful pattern in the beginning, a Standard that nature gave, and man could do no better in colors than that. He selected for white and obtained the Aylesbury and the Pekin, and as far as plumage is concerned these varieties are admired "because they look so pure and so clean." PEKIN DUCKS

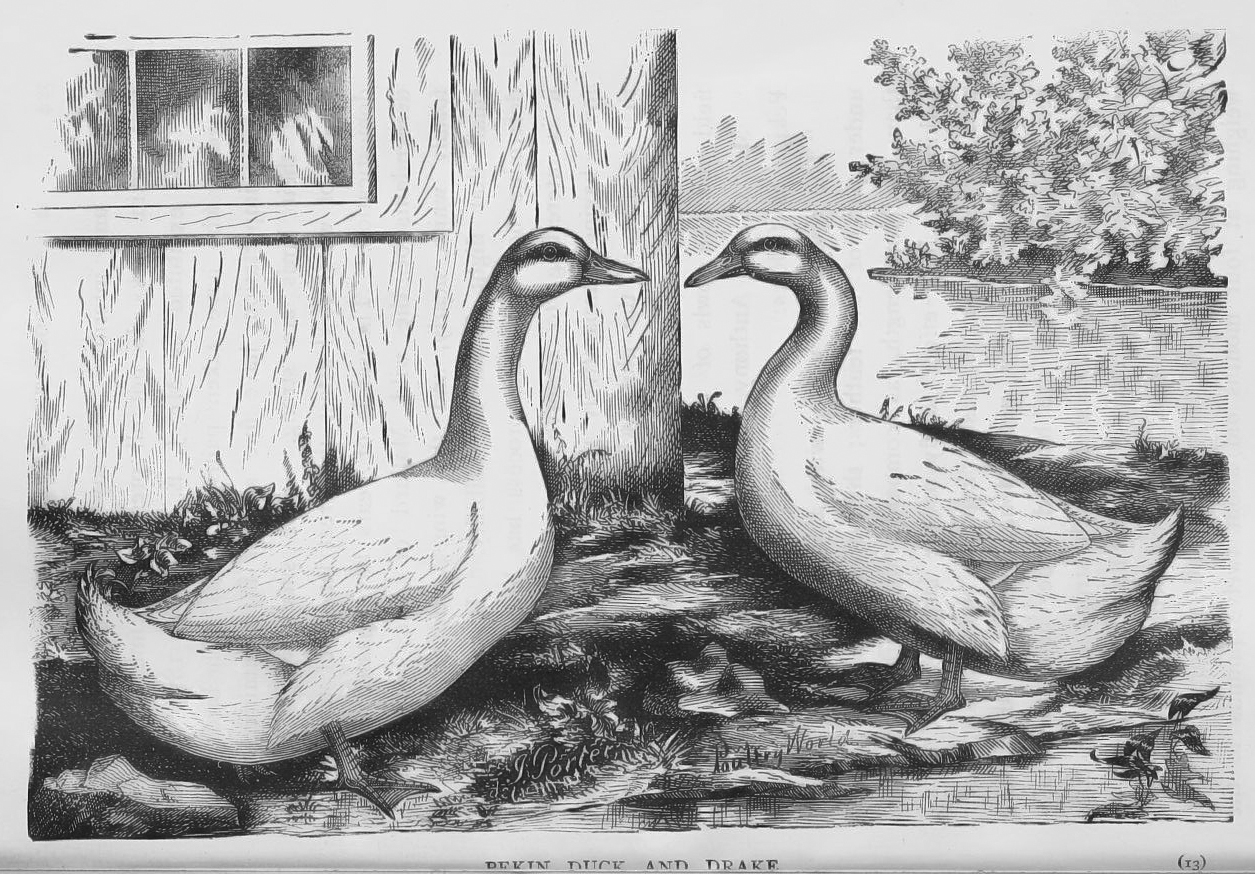

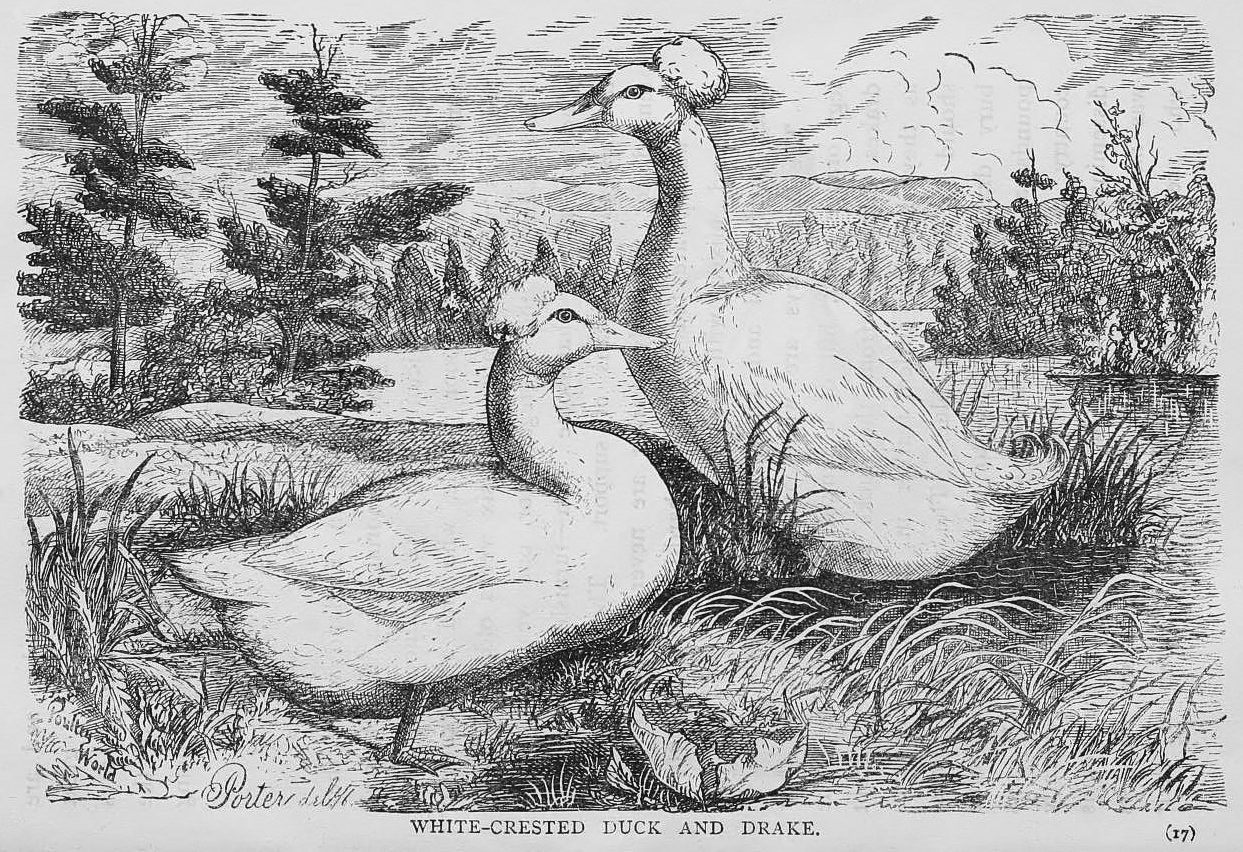

were first imported from China by Mr. J. E. Palmer, of Stonington, Conn., in the spring of 1873. They were at first mistaken for small-sized geese. They have long bodies, quite long necks, and carry their tails erect when startled. A large number were brought on shipboard, mostly young birds, but only a very few survived the passage. The importer saved a drake and three ducks. They are, without doubt, a larger bird than the Rouen, and for their beauty and size a great acquisition to our poultry stock. The bill is yellow, and the legs are a reddish or orange-yellow. The wings are short, and as they cannot fly well, it is quite easy to keep them in small inclosures. They are very prolific. Two of the ducks of the first importation laid nearly one hundred and twenty eggs each from the last of March to about the first of August. Pekin Ducks have taken their proper place in the list of domestic fowls, and are rightly esteemed for their size and white plumage. Having been rapidly disseminated through the country since the fir„t importation, they have had a trial in the North and South, East and West. The trial has, no doubt, been a very unfair one in many instances. This new breed has been thoughtlessly subjected to all the disadvantages of incest. Men have bought pairs, perhaps brother and sister, and bred them closely in successive years, the stock diminishing in size and vigor, till Pekins were banished as degenerate and inferior. We say this to explain the fact that Pekin ducks do not all present the fine appearance of those exhibited by Mr. J. E. Palmer in 1874. Those breeders who have taken pains to cross with birds from a later importation, have fine success in maintaining size, and their birds are strong. The small wings of this variety of water fowl attest the great length of time since domestication. Thousands of years have passed," and the descendants of the wild Mallard of Asia became uniformly white, nearly, and the wings, through disuse, so small that flight is an impossibility. It is not easy to determine how long this process has been going on, but it is interesting to observe that our largest breeds of fowls, having comparatively the smallest wings, come from that quarter of the globe where, probably, man has longest dwelt and exercised dominion over the beasts of the field and the fowls of the air. Mr. G. P. Anthony, of Westerly, R. I., writes of Pekins as follows: "The ducks are white, with a yellowish tinge to the under part of the feathers; their wings are a little less than medium length, as compared with other varieties, making as little effort to fly as the large Asiatic fowls, and they can be as easily kept in inclosures. Their beaks are yellow, their necks long, their legs short and red. When the eggs are hatched under hens, the ducklings come_ out of the shell much stronger, if the eggs are dampened every day — after the first fifteen days — in water a little above blood heat, and replaced under the hen. The ducks are very large and uniform in size, weighing at four months old about twelve pounds to the pair. They appear to be very hardy, not minding severe weather. Water to drink seems to be all they require to bring them to perfect development. I was more successful in rearing them with only a shallow dish filled to the depth of one inch with water than those which had the advantages of pond and running stream." Of the second importation of Pekin Ducks by Mr. Palmer, Rev. W. Clift writes: "They were brought down from Pekin to the coast by Major Ashley and put on board the vessel. The mortality among the ducks was much greater on their journey in China than on shipboard. They came through the long voyage in safety, and only one, a drake, died after landing. They were in thin condition, but rapidly recruited, and after a few days began to lay. As they had laid a good many eggs on their passage, for the benefit of the cook, it was not expected that they would lay the usual number of eggs, but their performance was very satisfactory in this respect. The drake which leads the flock is a very large bird, with bone enough to carry ten pounds. The largest duck weighs eight pounds, seven ounces, and a second duck is nearly as heavy. These weights are larger than any that the first importation attained during the first season, though they have been exceeded since. It is one of the good points of these birds that they improve in weight after they become acclimated, and there is a steady gain up to the third generation. This importation from the best stock in China, carefully selected by Major Ashley, is likely to have an important influence upon the breed in this country. "There is much danger of deterioration from in-and in breeding, and our best breeders are careful to avoid it. It will now be in the power of all breeders of Pekins to get new blood into their flocks at small expense. Drakes of the second importation, bred with ducks of the first, or the equivalent breeding in the other direction, will probably give the best results attainable. "Mr. Palmer's facilities for breeding ducks are unsurpassed. His place is located immediately upon a salt water cove, fed by a mill stream, and the ducks have free access to the endless variety of salt water food which every tide brings in, as well as the run of a large meadow, where grasses and insects abound. It is fortunate for the reputation of the breed that all these natural facilities are united with skillful management at headquarters." In the future much will depend upon judicious management in breeding Pekin ducks. Breeders have ascertained by experience that repeated in-breeding brings deterioration; and if large size, the desirable quality, is to be attained, there must be selection of the largest specimens for breeding, not near akin. This is a very old breed of ducks in a comparatively new country. In the East, both land and water fowls have been domesticated for an immense period of time, and large breeds have been slowly developed. A Chinese Encyclopedia, published in 1609, but compiled from documents still older, states that fowls were kept in China over three thousand years ago. WHITE-CRESTED DUCKS. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD