History of the Johnstown Flood

By Willis Fletcher Johnson

Chapter 15

|

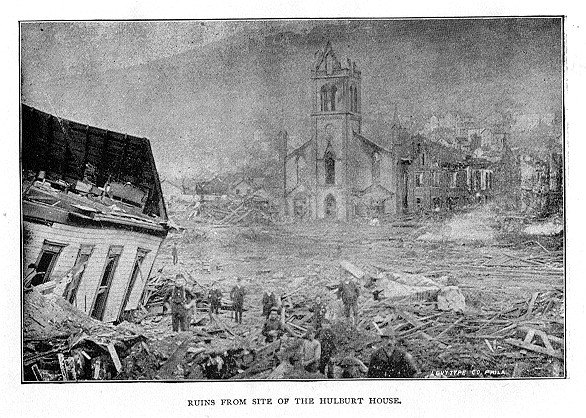

Five days after the disaster a bird's-eye view was taken of Johnstown from the top of a precipitous mountain which almost overhangs it. The first thing that impresses the eye, wrote the observer, is the fact that the proportion of the town that remains uninjured is much smaller than it seems to be from lower-down points of view. Besides the part of the town that is utterly wiped out, there are two great swaths cut through that portion which from lower down seems almost uninjured. Beginning at Conemaugh, two miles above the railroad bridge, along the right side of the valley looking down, there is a strip of an eighth by a quarter of a mile wide, which constituted the heart of a chain of continuous towns, sand which was thickly built over for the whole distance, upon which now not a solitary building stands except the gutted walls of the Wood, Morrell & Co. general store in Johnstown, and of the Gautier wire mill and Woodvale flour mill at Woodvale. Except for these buildings, the whole two-mile strip is swept clean, not only of buildings, but of everything. It is a tract of mud, rocks, and such other miscellaneous debris as might follow the workings of a huge hydraulic placer mining system in the gold regions. In Johnstown itself, besides the total destruction upon this strip, extending at the end to cover the whole lower end of the city, there is a swath branching off from the main strip above the general store and running straight to the bluff. It is three blocks wide and makes a huge "Y," with the gap through which the flood came for the base and main strip and the swaths for branches. Between the branches there is a triangular block of buildings that are still standing, although most of them are damaged. At a point exactly opposite the corner where the branches of the "Y" meet, and distant from it by about fifty yards, is one of the freaks of the flood. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad station, a square, two-story brick building, with a little cupola at the apex of its slanting roof, is apparently uninjured, but really one corner is knocked in and the whole interior is a total wreck. How it stood when everything anywhere near it was swept away is a mystery. Above the "Y"-shaped tract of ruin there is another still wider swath, bending around in Stony Creek, save on the left, where the flood surged when it was checked and thrown back by the railroad bridge. It swept things clean before it through Johnstown and made a track of ruin among the light frame houses for nearly two miles up the gap. The Roman Catholic Church was just at its upper edge. It is still standing, and from its tower the bell strikes the hours regularly as before, although everybody now is noticing that it always sounds like a funeral. Nobody ever noticed it before, but from the upper side it can be seen that a huge hole has been knocked through the side of the building. A train of cars could be run through it. Inside the church is filled with all sorts of rubbish and ruin. A little further on is another church, which curiously illustrates the manner in which fire and flood seemed determined to unite in completing the ruin of the city. Just before the flood came down the valley there was a terrific explosion in this church, supposed to have been caused by natural gas. Amid all the terrors of the flood, with the water surging thirty feet deep all around and through it, the flames blazed through the roof and tower, and its fire stained walls arise from the debris of the flood, which covers its foundations. Its ruins are one of the most conspicuous and picturesque sights in the city.

Next to Adams Street, the road most traveled in Johnstown now is the Pennsylvania Railroad track, or rather bed, across the Stony Creek, and at a culvert crossing just west of the creek. More people have been injured here since the calamity than at any other place. The railroad ties which hold the track across the culvert are big ones, and their strength has not been weakened by the flood, but between the ties and between the freight and passenger tracks there is a wide space. The Pennsylvania trains from Johnstown have to stop, of course, at the eastern end of the bridge, and the thousands of people whom they daily bring to Johnstown from Pittsburgh have to get into Johnstown by walking across the track to the Pennsylvania Railroad depot, and then crossing the pontoon foot-bridge that has been built across the Stony Creek. All day long there is a black line of people going back and forth across this course. Every now and then there is a yell, a plunge, a rush of people to the culvert, a call for a doctor, and cries of "Help" from underneath the culvert. Some one, of course, has fallen between the freight and passenger tracks, or between the ties of the tracks themselves. In the night it is particularly dangerous traveling to the Pennsylvania depot this way, and people falling then have little change of a rescue. So far at least thirty persons have fallen down the culvert, and a dozen of them, who have descended entirely to the ground, have escaped in some marvelous manner with their lives. Several Pittsburghers have had their legs and arms broken, and one man cracked his collar-bone. It is to be hoped that these accidents will keep off the flock of curiosity-seekers , in some degree at least. The presence of these crowds seriously interferes with the work of clearing up the town, and affects the residents here in even a graver manner, for though many of those coming to Johnstown to spend a day and see the ruins bring something to eat with them, many do not do so, and invade the relief stands, taking the food which is lavishly dealt out to the suffering. Though the Pennsylvania Railroad bridge is as strong as ever, apparently, beyond the bridge, the embankment on which the track is built is washed away, and people therefore do not cross the bridge, but leave the track on the western side, and, clambering down the abutments, cross the creek on a rude foot-bridge hastily erected, and then through the yard of the Open-Hearth Works and of the railroad up to the depot. This yard altogether is about three-quarters of a mile long, but so deceptive are distances in the valley that it does not look one-third that. The bed of this yard, three-quarters of a mile long, and about the same distance wide, is the most desolate place here. The yard itself is fringed with the crumbling ruins of the iron works and the railroad shops. The iron works were great, high brick buildings, with steep iron roofs. The ends of these buildings were smashed in, and the roofs bend over where the flood struck them, in a curve. But it is the bed of the yard itself that is desolate. In appearance it is a mass of stones and rocks and huge boulders, so that it seems a vast quarry hewn and uncovered by the wind. There is comparatively little debris here, all this having been washed away over to the sides of the buildings, in one or two instances filling the buildings completely. There is no soft earth or mud on the rocks at all, this part of Johnstown being much in contrast with the great stretch of sand along the river. In some instances the dirt is washed away to such a depth that the bed-rock is uncovered. The fury of the waters here may be gathered from this fact: piled up outside the works of the Open-Hearth Company were several heaps of massive blooms - long, solid blocks of pig iron, weighing fifteen tons each. The blooms, though they were not carried down the river, were scattered about the yard like so many logs of wood. They will have to be piled up again by the use of a derrick. The Open-Hearth Iron Works people are making vigorous efforts to clean their buildings. The yards of the company were blazing last night with the burning debris, but it will be weeks before the company can start operations. In the Pennsylvania Railroad yard all is activity and bustle. At the relief station, and at the headquarters of General Hastings, in the signal tower, the man who is the head of all operations there, and the directing genius of the place, is Lieutenant George Miller, of the Fifth United States Infantry. Lieutenant Miller was near here on his vacation when the flood came. He was one of the first on the spot, and was about the only man in Johnstown who showed some ability as an organizer and a disciplinarian. A reporter who groped his way across the railroad track, the foot-bridge, and the quarries and yards at reveille found Lieutenant Miller in a group of the soldiers of the Fourteenth Pennsylvania Regiment telling them just what to do.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD