History of the Johnstown Flood

By Willis Fletcher Johnson

Chapter 9

|

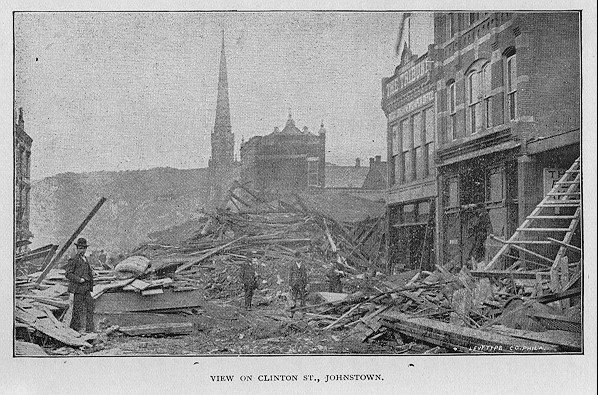

MANY of the most thrilling sights and experiences were those of railroad employees and passengers. Mr. Henry, the engineer of the second section of express train No. 8, which runs between Pittsburg and Altoona, was at Conemaugh when the great flood came sweeping down the valley. He was able to escape to a place of safety. His was the only train that was not injured, even though it was in the midst of the great wave. The story as related by Mr. Henry is most graphic. "It was an awful sight," he said. "I have often seen pictures of flood scenes and I thought they were exaggerations, but what I witnessed last Friday changes my former belief. To see that immense volume of water, fully fifty feet high, rushing madly down the valley, sweeping everything before it, was a thrilling sight. It is engraved indelibly on my memory. Even now I can see that mad torrent carrying death and destruction before it. "The second section of No. 8, on which I was, was due at Johnstown about quarter past ten in the morning. We arrived there safely and were told to follow the first section. When we arrived at Conemaugh the first section and the mail were there. Washouts further up the mountain prevented our going on, so we could do nothing but sit around and discuss the situation. The creek at Conemaugh was swollen high, almost overflowing. The heavens were pouring rain, but this did not prevent nearly all the inhabitants of the town from gathering along its banks. They watched the waters go dashing by and wondered whether the creek would get much higher. But a few inches more and it would overflow its banks. There seemed to be a feeling of uneasiness among the people. They seemed to fear that something awful was going to happen. Their suspicions were strengthened by the fact that warning had come down the valley for the people to be on the lookout. The rains had swollen everything to the bursting point. They day passed slowly, however. Noon came and went, and still nothing happened. We could not proceed, nor could we go back, as the tracks about a mile below Conemaugh had been washed away, so there was nothing for us to do but to wait and see what would come next. "Some time after three o'clock Friday afternoon I went into the train dispatcher's office to learn the latest news. I had not been there long when I heard a fierce whistling from an engine away up the mountain. Rushing out I found dozens of men standing around. Fear had blanched every cheek. The loud and continued whistling had made every one feel that something serious was going to happen. In a few moments I could hear a train rattling down the mountain. About five hundred yards above Conemaugh the tracks make a slight curve and we could not see beyond this. The suspense was something awful. We did not know what was coming, but no one could get rid of the thought that something was wrong at the dam. "Our suspense was not very long, however. Nearer and nearer the train came, the thundering sound still accompanying it. There seemed to be something behind the train, as there was a dull, rumbling sound which I knew did not come from the train. Nearer and nearer it came; a moment more and it would reach the curve. The next instant there burst upon our eyes a sight that made every heart stand still. Rushing around the curve, snorting and tearing, came an engine and several gravel cars. The train appeared to be putting forth every effort to go faster. Nearer it came, belching forth smoke and whistling long and loud. But the most terrible sight was to follow. Twenty feet behind came surging along a mad rush of water fully fifty feet high. Like the train, it seemed to be putting forth every effort to push along faster. Such an awful race we never before witnessed. For an instant the people seemed paralyzed with horror. They knew not what to do, but in a moment they realized that a second's delay meant death to them. With one accord they rushed to the high lands a few hundred feet away. Most of them succeeded in reaching that place and were safe. "I thought of the passengers in my train. The second section of No. 8 had three sleepers. In these three cars were about thirty people, who rushed through the train crying to the others 'Save yourselves!' Then came a scene of the wildest confusion. Ladies and children shrieked and the men seemed terror-stricken. I succeeded in helping some ladies and children off the train and up to the high lands. Running back, I caught up two children and ran for my life to a higher place. Thank God, I was quicker than the flood! I deposited my load in safety on the high land just as it swept past us. "For nearly an hour we stood watching the mad flood go rushing by. The water was full of debris. When the flood caught Conemaugh it dashed against the little town with a mighty crash. The water did not lift the houses up and carry them off, but crushed them up one against the other and broke them up like so many egg-shells. Before the flood came there was a pretty little town. When the waters passed on there was nothing but a few broken boards to mark the central portion of the city. It was swept as clean as a newly-brushed floor. When the flood passed onward down the valley I went over to my train. It had been moved back about twenty yards, but it was not damaged. About fifteen persons had remained in the train and they were safe. Of the three trains ours was the luckiest. The engines of both the others had been swept off the track, and one or two cars in each train had met the same fate. What saved our train was the fact that just at the curve which I mentioned the valley spread out. The valley is six or seven hundred yards broad where our train was standing. This, of course, let the floods pass out. It was only about twenty feet high when it struck our train, which was about in the middle of the valley. This fact, together with the elevation of the track, was all that saved us. We stayed that night in the houses in Conemaugh that had not been destroyed. The next morning I started down the valley and by four o'clock in the afternoon had reached Conemaugh furnace, eight miles west of Johnstown. Then I got a team and came home. "In my tramp down the valley I saw some awful sights. On the tree branches hung shreds of clothing torn from the unfortunates as they were whirled along in the terrible rush of the torrent. Dead bodies were lying by scores along the banks of the creeks. One woman I helped drag from the mud had tightly clutched in her hand a paper. We tore it out of her hand and found it to be a badly water-soaked photograph. It was probably a picture of the drowned woman." Pemberton Smith is a civil engineer employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad. On Friday, when the disaster occurred, he was at Johnstown, stopping at the Merchants' Hotel. What happened he described as follows: "In the afternoon, with four associates, I spent the time playing checkers in the hotel, the streets being flooded during the day. At half-past four we were startled by shrill whistles. Thinking a fire was the cause, we looked out of the window. Great masses of people were rushing through the water in the street, which had been there all day, and still we thought the alarm was fire. All of a sudden the roar of the water burst upon our ears, and in an instant more the streets were filled with debris. Great houses and business blocks began to topple and crash into each other and go down as if they were toy-block houses. People in the streets were drowning on all sides. One of our company started down-strairs and was drowned. The other four, including myself, started up-stairs, for the water was fast rising. When we got on the roof we could see whole blocks swept away as if by magic. Hundreds of people were floating by, clinging to roofs of houses, rafts, timbers, or anything they could get a hold of. The hotel began to tremble, and we made our way to an adjoining roof. Soon afterward part of the hotel went down. The brick structures seemed to fare worse than frame buildings, as the latter would float, while the brick would crash and tumble into one great mass of ruins. We finally climbed into a room of the last building in reach and stayed there all night, in company with one hundred and sixteen other people, among the number being a crazy man. His wife and family had all been drowned only a few hours before, and he was a raving maniac. And what a night! Sleep! Yes, I did a little, but every now and then a building near by would crash against us, and we would all jump, fearing that at last our time had come. "Finally morning dawned. In company with one of my associates we climbed across the tops of houses and floating debris, built a raft, and poled ourselves ashore to the hillside. I don't know how the others escaped. This was seven o'clock on Saturday morning. We started on foot for South Fork, arriving there at three P. M. Here we found that all communication by telegraph and railroad was cut off by the flood, and we had naught to do but retrace our steps. Tired and footsore! Well, I should say so. My gum-boots had chafed my feet so I could hardly walk at all. The distance we covered on foot was over fifty miles. On Sunday we got a train to Altoona. Here we found the railroad connections all cut off, so we came back to Johnstown again on Monday. What a desolate place! I had to obtain a pass to go over into the city. Here it is: "Pass Pemberton Smith through all the streets. "Alec. Hart, Chief of Police. "A.J. Maxham, Acting Mayor." "The tragic pen-pictures of the scenes in the press dispatches have not been exaggerated. They cannot be. The worse sight of all was to see the great fire at the railroad-bridge. It makes my blood fairly curdle to think of it. I could see the lurid flames shoot heavenward all night Friday, and at the same time hundreds of people were floating right toward them on top of houses, etc., and to meet a worse death than drowning. To look at a sight like this and not be able to render a particle of assistance seemed awful to bear. I had a narrow escape, truly. In my mind I can hear the shrieks of men, women, and children, the maniac's ravings, and the wild roar of a sea of water sweeping everything before it."

Among the lost was Miss Jennie Paulson, a passenger on a railroad train, whose fate is thus described by one of her comrades: "We had been making but slow progress all the day. Our train lay at Johnstown nearly the whole day of Friday. We then proceeded as far as Conemaugh, and had stopped from some cause or other, probably on account of the flood. Miss Paulson and a Miss Bryan were seated in front of me. Miss Paulson had on a plaid dress, with shirred waist of red cloth goods. Her companion was dressed in black. Both had lovely corsage bouquets of roses. I had heard that they had been attending a wedding before they left Pittsburg. The Pittsburg lady was reading a novel entitled Miss Lou. Miss Bryan was looking out of the window. When the alarm came we all sprang toward the door, leaving everything behind us. I had just reached the door when poor Miss Paulson and her friend, who were behind me, decided to return for their rubbers, which they did. I sprang from the car into a ditch next the hillside, in which the water was already a foot and a-half deep, and, with the others, climbed up the mountain side for our very lives. We had to do so, as the water glided up after us like a huge serpent. Any one ten feet behind up would have been lost beyond a doubt. I glanced back at the train when I had reached a place of safety, but the water already covered it, and the Pullman car in which the ladies were was already rolling down the valley in the grasp of the angry waters." Mr. William Scheerer, the teller of the State Banking Company, of Newark, N.J. was among the passengers on the ill-fated day express on the Pennsylvania Railroad that left Pittsburg at eight o'clock A.M., on the now historic Friday, bound for New York. There was some delays incidental to the floods in the Conemaugh Valley before the train reached Johnstown, and a further delay at that point, and the train was considerably behind time when it left Johnstown. Said Mr. Scheerer: "The parlor car was fully occupied when I went aboard the train, and a seat was accordingly given me in the sleeper at the rear end of the train. There were several passengers in this car, how many I cannot say exactly, among them some ladies. It was raining hard all the time and we were not a very excited nor a happy crowd, but were whiling away the time in reading and in looking at the swollen torrent of the river. Very few of the people were apprehensive of any danger in the situation, even after we had been held up at Conemaugh for nearly five hours. "The railroad tracks where our train stopped were full fourteen feet above the level of the river, and there was a large number of freight and passenger cars and locomotives standing on the tracks near us and strung along up the road for a considerable distance. Between the road and the hill that lay at our left there was a ditch, through which the water that came down from the hill was running like a mill-race. It was a monotonous wait to all of us, and after a time many inquiries were made as to why we did not go ahead. Some of the passengers who made the inquiry were answered laconically—'Wash-out,' and with this they had to be satisfied. I had been over the road several times before, and knew of the existence of the dangerous and threatening dam up in the South Fork gorge, and could not help connecting it in my mind with the cause of our delay. But neither was I apprehensive of danger, for the possibility of the dam giving away had been often discussed by passengers in my presence, and everybody supposed that the utmost damage it would do when it broke, as everybody believed it sometime would, would be to swell a little higher the current that tore down through the Conemaugh Valley. "Such a possibility as the carrying away of a train of cars on the great Pennsylvania road was never seriously entertained by anybody. We had stood stationary until about four o'clock, when two colored porters went through the car within a short time of each other, looking and acting rather excited. I asked the first one what the matter was, and he replied that he did not know. I inferred from his reply that if there was any thing serious up, the passengers would be informed, and so I went on reading. When the next man came along I asked him if the reservoir had given way, and he said he thought it had. "I put down my book and stepped out quickly to the rear platform, and was horrified at the sight that met my gaze up the valley. It seemed as if a forest was coming down upon us. There as a great wall of water roaring and grinding swiftly along, so thickly studded with the trees from along the mountain sides that it looked like a gigantic avalanche of trees. Of course I lingered but an instant, for the mortal danger we all were in flashed upon me at the first sight of that terrible on-coming torrent. But in that instant I saw an engine lifted bodily off the track and thrown over backward into the whirlpool, where it disappeared, and houses crushed and broken up in the flash of an eye. "The noise was like incessant thunder. I turned back into the car and shouted to the ladies, three of whom alone were in the car at the moment, to fly for their lives. I helped them out of the car on the side toward the hill, and urged them to jump across the ditch and run for their lives. Two of them did so, but the third, a rather heavy lady, a missionary, who was on her way to a foreign station, hesitated for an instant, doubtful if she could make the jump. That instant cost her her life. While I was holding out my hand to her and urging her to jump, the rush of the waters came down and swept her, like a doll, down into the torrent. In the same instant an engine was thrown from the track into the ditch at my feet. The water was about my knees as I turned and scrambled up the hill, and when I looked back, ten seconds later, it was surging and grinding ten feet deep over the track I had just left. "The rush of waters lasted three-quarters of an hour, while we stood rapt and spell-bound in the rain, looking at the ruin no human agency could avert. The scene was beyond the power of language to describe. You would see a building standing in apparent security above the swollen banks of the river, the people rushing about the doors, some seeming to think that safety lay indoors, while others rushed toward higher ground, stumbling and falling in the muddy streets, and then the flood rolled over them, crushing in the house with a crash like thunder, and burying house and people out of sight entirely. That, of course, was the scene in only an instant, for our range of vision was only over a small portion of the city. "We sought shelter from the rain in the home of a farmer who lived high up on the side-hill, and the next morning walked down to Johnstown and viewed the ruins. It seemed as if the city was utterly destroyed. The water was deep over all the city and few people were visible. We returned to Conemaugh and were driven over the mountains to Ebensburg, where we took the train for Altoona, but finding we could get no further in that direction we turned back to Ebensburg, and from there went by wagon to Johnstown, where we found a train that took us to Pittsburg. I got home by the New York Central."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD