Birds and Their Nests

By Mary Howitt

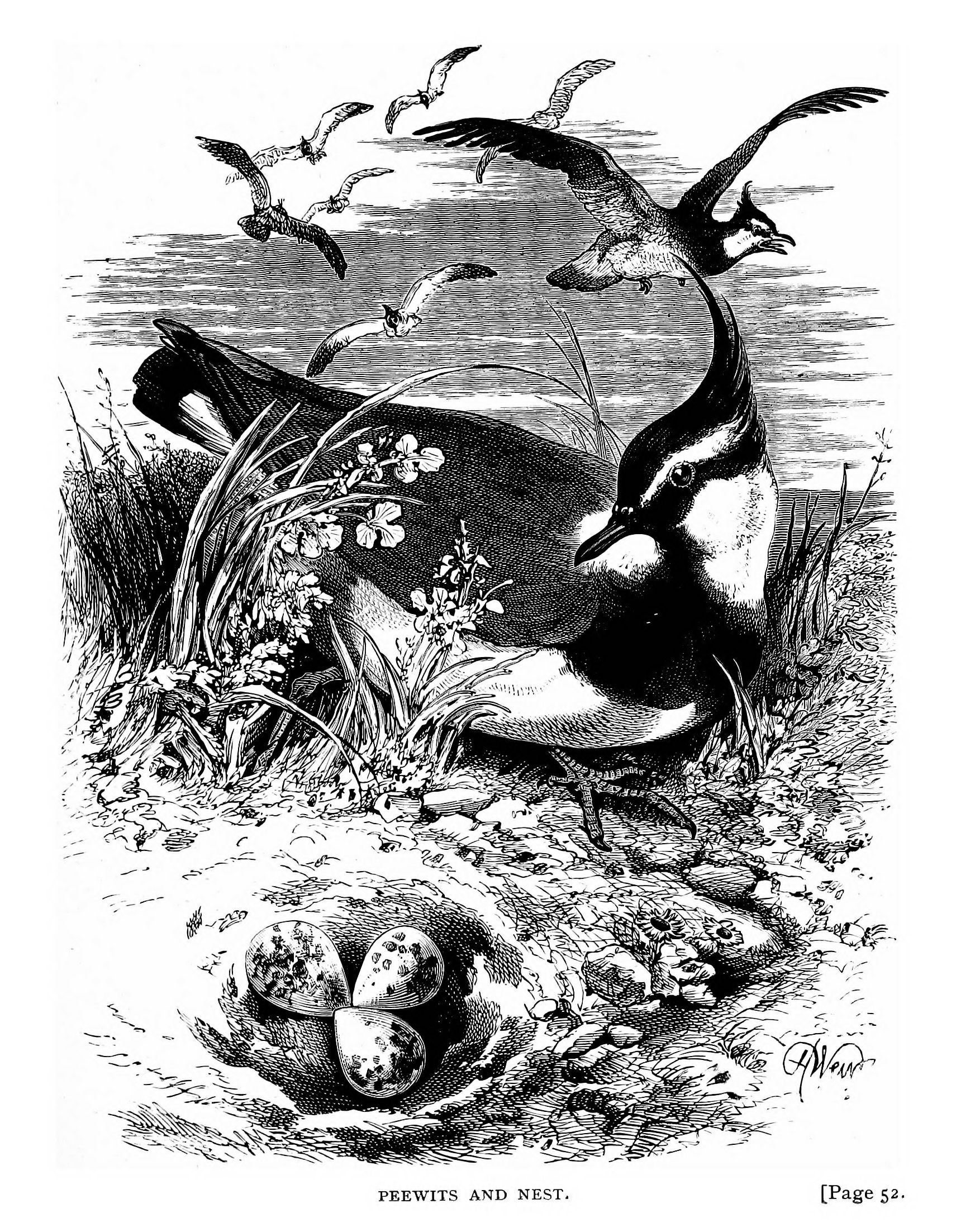

CHAPTER IX.THE PEEWIT.The Peewit, lapwing, or plover, belongs to the naturalist family of Gallatores or Waders, all of which are furnished with strong legs and feet for walking, whilst all which inhabit watery places, or feed their young amongst the waves, have legs sufficiently long to enable them to wade; whence comes the family name. The peewit, or lapwing, is a very interesting bird, from its peculiar character and habits. Its plumage is handsome; the upper part of the body of a rich green, with metallic reflections; the sides of the neck and base of the tail of a pure white; the tail is black; so is the top of the head, which is furnished with a long, painted crest, lying backwards, but which can be raised at pleasure. In length the bird is about a foot. The peewit lives in all parts of this country, and furnishes one of the pleasantly peculiar features of open sea-shores and wide moorland wastes, in the solitudes of which, its incessant, plaintive cry has an especially befitting sound, like the very spirit of the scene, moaning in unison with the waves, and wailing over the wide melancholy of the waste. Nevertheless, the peewit is not in itself mournful, for it is a particularly lively and active bird, sporting and frolicking in the air with its fellows, now whirling round and round, and now ascending to a great height on untiring wing; then down again, running along the ground, and leaping about from spot to spot as if for very amusement. It is, however, with all its agility, a very untidy nest-maker; in fact it makes no better nest than a few dry bents scraped together in a shallow hole, like a rude saucer or dish, in which she can lay her eggs -- always four in number. But though taking so little trouble about her nest, she is always careful to lay the narrow ends of her eggs in the centre, as is shown in the picture, though as yet there are but three. A fourth, however, will soon come to complete the cross-like figure, after which she will begin to sit. These eggs, under the name of plovers' eggs, are in great request as luxuries for the breakfast-table, and it may be thought that laid thus openly on the bare earth they are very easily found. It is not so, however, for they look so much like the ground itself, so like little bits of moorland earth or old sea-side stone, that it is difficult to distinguish them. But in proportion as the bird makes so insufficient and unguarded a nest, so all the greater is the anxiety, both of herself and her mate, about the eggs. Hence, whilst she is sitting, he exercises all kinds of little arts to entice away every intruder from the nest, wheeling round and round in the air near him, so as to fix his attention, screaming mournfully his incessant pee-wit till he has drawn him ever further and further from the point of his anxiety and love. The little quartette brood, which are covered with down when hatched, begin to run almost as soon as they leave the shell, and then the poor mother-bird has to exercise all her little arts also -- and indeed the care and solicitude of both parents is wonderful. Suppose, now, the little helpless group is out running here and there as merry as life can make them, and a man, a boy, or a dog, or perhaps all three, are seen approaching. At once the little birds squat close to the earth, so that they become almost invisible, and the parent-birds are on the alert, whirling round and round the disturber, angry and troubled, wailing and crying their doleful pee-wit cry, drawing them ever further and further away from the brood. Should, however, the artifice not succeed, and the terrible intruder still obstinately advance in the direction of the young, they try a new artifice; drop to the ground, and,' running along in the opposite course, pretend lameness, tumbling feebly along in the most artful manner, thus apparently offering the easiest and most tempting prey, till, having safely lured away the enemy, they rise at once into the air, screaming again their pee-wit, but now as if laughing over their accomplished scheme. The young, which are hatched in April, are in full plumage by the end of July, when the birds assemble in flocks, and, leaving the sea-shore, or the marshy moorland, betake themselves to downs and sheep-walks, where they soon become fat, and are said to be excellent eating. Happily, however, for them, they are not in as much request for the table as they were in former times. Thus we find in an ancient book of housekeeping expenses, called " The Northumberland Household-book," that they are entered under the name of Wypes, and charged one penny each; and that they were then considered a first-rate dish is proved by their being entered as forming a part of "his lordship's own mess," or portion of food; mess being so used in those days -- about the time, probably, when the Bible was translated into English. Thus we find in the beautiful history of Joseph and his brethren, " He sent messes to them, but Benjamin's mess was five times as much as any of theirs." Here I would remark, on the old name of Wypes for this bird, that country-people in the midland counties still call them pieæpes. But now again to our birds. The peewit, like the gull, may easily be tamed to live in gardens, where it is not only useful by ridding them of worms, slugs, and other troublesome creatures, but is very amusing, from its quaint, odd ways. Bewick tells us of one so kept by the Rev. J. Carlisle, Vicar of Newcastle, which I am sure will interest my readers. He says two of these birds were given to Mr. Carlisle, and placed in his garden, where one soon died; the other continued to pick up such food as the place afforded, till winter deprived it of its usual supply. Necessity then compelled it to come nearer the house, by which it gradually became accustomed to what went forward, as well as to the various members of the family. At length a servant, when she had occasion to go into the back-kitchen with a light, observed that the lapwing always uttered his cry of pee-wit to gain admittance. He soon grew familiar; as the winter advanced, he approached as far as the kitchen, but with much caution, as that part of the house was generally inhabited by a dog and a cat, whose friendship the lapwing at length gained so entirely, that it was his regular custom to resort to the fireside as soon as it grew dark, and spend the evening and night with his two associates, sitting close to them, and partaking of the comforts of a warm fireside. As soon as spring- appeared he betook himself to the garden, but again, at the approach of winter, had recourse to his old shelter and his old friends, who received him very cordially. But his being favoured by them did not prevent his taking great liberties with them; he would frequently amuse himself with washing in the bowl which was set for the dog to drink out of, and whilst he was thus employed he showed marks of the greatest indignation if either of his companions presumed to interrupt him. He died, poor fellow, in the asylum he had chosen, by being choked with something which he had picked up from the floor. During his confinement he acquired an artifical taste as regarded his food, and preferred crumbs of bread to anything else.

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD