Birds and Their Nests

By Mary Howitt

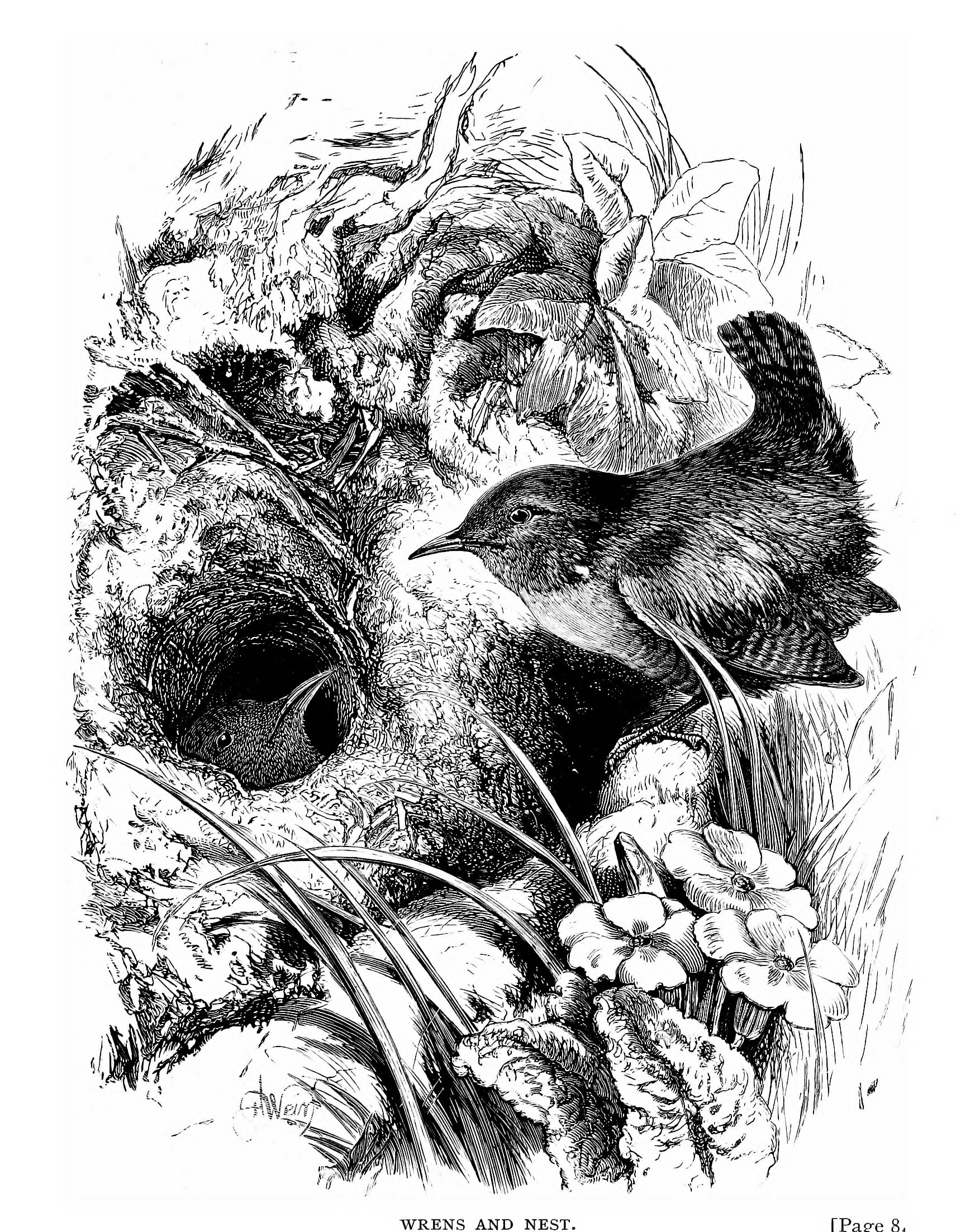

CHAPTER I.THE WREN.Truly the little Wren, so beautifully depicted by Mr. Harrison Weir., with her tiny body, her pretty, lively, and conceited ways, her short, little turned-up tail, and delicate plumage, is worthy of our tender regard and love. The colouring of the wren is soft and subdued -- a reddish-brown colour; the breast of a light greyish-brown; and all the hinder parts, both above and below, marked with wavy lines of dusky brown, with two bands of white dots across the wings. Its habits are remarkably lively and attractive. " I know no pleasanter object," says the agreeable author of "British Birds," "than the wren; it is always* so smart and cheerful. In gloomy weather other birds often seem melancholy, and in rain the sparrows and finches stand silent on the twigs, with drooping wings and disarranged plumage; but to the merry little wren all weathers are alike. The big drops of the thundershower no more wet it than the drizzle of a Scotch mist; and as it peeps from beneath the bramble, or glances from a hole in the wall, it seems as snug as a kitten frisking on the parlour rug. "It is amusing," he continues, "to watch the motions of a young family of wrens just come abroad. Walking among furze, broom, or juniper, you are attracted to some bush by hearing Issue from it the frequent repetition of a sound resembling the syllable chit. On going up you perceive an old wren flitting about the twigs, and presently a young one flies off, uttering a stifled chirr, to conceal itself among the bushes. Several follow, whilst the parents continue to flutter about in great alarm, uttering their chit, chit, with various degrees of excitement." The nest of the wren is a wonderful structure, of which I shall have a good deal to say. It begins building in April, and is not by any means particular in situation. Sometimes it builds in the hole of a wall or tree; sometimes, as in this lovely little picture of ours, in the mossy hollow of a primrose-covered bank; and because it was formerly supposed to live only in holes or little caves, it received the name of Troglodytes, or cave-dweller. But it builds equally willingly in the thatch of outbuildings, in barn-lofts, or tree-branches, either when growing apart or nailed against a wall, amongst ivy or other climbing plants; in fact, it seems to be of such a happy disposition as to adapt itself to a great variety of situations. It is a singular fact that it will often build several nests in one season -- not that It needs so many separate dwellings, or that It finishes them when built; but it builds as If for the very pleasure of the work. Our naturalist says, speaking of this odd propensity, "that, whilst the hen Is sitting, the he-bird, as if from a desire to be doing something, will construct as many as half-a-dozen nests near the first, none of which, however, are lined with feathers; and that whilst the true nest, on which the mother-bird is sitting, will be carefully concealed, these sham nests are open to view. Some say that as the wrens, during the cold weather, sleep in some snug, warm hole, they frequently occupy these extra nests as winter-bedchambers, four or five, or even more, huddling together, to keep one another warm." Mr. Weir, a friend of the author I have just quoted, says this was the case in his own garden; and that, during the winter, when the ground was covered with snow, two of the extra-nests were occupied at night by a little family of seven, which had hatched in the garden. He was very observant of their ways, and says it was amusing to see one of the old wrens, coming a little before sunset and standing a few inches from the nest, utter his little cry till the whole number of them had arrived. Nor were they long about it; they very soon answered the call, flying from all quarters -- the seven young ones and the other parent-bird -- and then at once nestled into their snug little dormitory. It was also remarkable that when the wind blew from the east they occupied a nest which had its opening to the west, and when it blew from the west, then one that opened to the east, so that it was evident they knew how to make themselves comfortable. And now as regards the building of these little homes. I will, as far as I am able, give you the details of the whole business from the diary of the same gentleman, which is as accurate as if the little wren had kept it himself, and which will just as well refer to the little nest in the primrose bank as to the nest in the Spanish juniper-tree, where, in fact, it was built. "On the 30th of May, therefore, you must imagine a little pair of wrens, having, after a great deal of consultation, made up their minds to build themselves a home in the branches of a Spanish juniper. The female, at about seven o'clock in the morning, laid the foundation with the decayed leaf of a limetree. Some men were at work cutting a drain not far off, but she took no notice of them, and worked away industriously, carrying to her work bundles of dead leaves as big as herself, her mate, seeming the while to be delighted with her industry, seated not far off in a Portugal laurel, where he watched her, singing to her, and so doing, making her labour, no doubt, light and pleasant. From eight o'clock to nine she worked like a little slave, carrying in leaves, and then selecting from them such as suited her purpose and putting aside the rest. This was the foundation of the nest, which she rendered compact by pressing it down with her breast, and turning herself round in it: then she began to rear the sides. And now the delicate and difficult part of the work began, and she was often away for eight or ten minutes together. From the inside she built the underpart of the aperture with the stalks of leaves, which she fitted together very ingeniously with moss. The upper part of it was constructed solely with the last-mentioned material. To round it and give it the requisite solidity, she pressed it with her breast and wings, turning the body round in various directions. Most wonderful to tell, about seven o'clock in the evening the whole outside workmanship of this snug little erection was almost complete. "Being very anxious to examine the interior of it, I went out for that purpose at half-past two the next morning. I introduced my finger, the birds not being there, and found its structure so close, that though it had rained in the night, yet that it was quite dry. The birds at this early hour were singing as if in ecstasy, and at about three o'clock the little he-wren came and surveyed his domicile with evident satisfaction; then, flying to the top of a tree, began singing most merrily. In half-an-hour's time the hen-bird made her appearance, and, going into the nest, remained there about five minutes, rounding the entrance by pressing it with her breast and the shoulders of her wings. For the next hour she went out and came back five times with fine moss in her bill, with which she adjusted a small depression in the fore-part of it; then, after twenty minutes' absence, returned with a bundle of leaves to fill up a vacancy which she had discovered in the back of the structure. Although it was a cold morning, with wind and rain, the male bird sang delightfully; but between seven and eight o'clock, either having received a reproof from his wife for his indolence, or being himself seized with an impulse to work, he began to help her, and for the next ten minutes brought in moss, and worked at the inside of the nest. At eleven o'clock both of them flew off, either for a little recreation, or for their dinners, and were away till a little after one. From this time till four o'clock both worked industriously, bringing in fine moss; then, during another hour, the hen-bird brought in a feather three times. So that day came to an end. "The next morning, June 1st, they did not begin their work early, as was evident to Mr. Weir, because having placed a slender leaf-stalk at the entrance, there it remained till half-past eight o'clock, when the two began to work as the day before with fine moss, the he-bird leaving off, however, every now and then to express his satisfaction on a near tree-top. Again, this day, they went off either for dinner or amusement; then came back and worked for another hour, bringing in fine moss and feathers. "The next morning the little he-wren seemed in a regular ecstasy, and sang incessantly till half-past nine, when they both brought in moss and feathers, working on for about two hours, and again they went off, remaining away an hour later than usual. Their work was now nearly over, and they seemed to be taking their leisure, when all at once the hen-bird, who was sitting in her nest and looking out at her door, espied a man half-hidden by an arbor vitae. It was no other than her good friend, but that she did not know; all men were terrible, as enemies to her race, and at once she set up her cry of alarm. The he-bird, on hearing this, appeared in a great state of agitation, and though the frightful monster immediately ran off, the little creatures pursued him, scolding vehemently. "The next day they worked again with feathers and fine moss, and again went off after having brought in a few more feathers. So they did for the next five days; working leisurely, and latterly only with feathers. On the tenth day the nest was finished, and the little mother-bird laid her first egg in it." Where is the boy, let him be as ruthless a bird-nester as he may, who could have the heart to take a wren's nest, only to tear it to pieces, after reading the history of this patient labour of love? The wren, like various other small birds, cannot bear that their nests or eggs should be touched; they are always disturbed and distressed by it, and sometimes even will desert their nest and eggs in consequence. On one occasion, therefore, this good, kind-hearted friend of every bird that builds, carefully put his finger into a wren's nest, during the mother's absence, to ascertain whether the young were hatched; on her return. perceiving that the entrance had been touched, she set up a doleful lamentation, carefully rounded it again with her breast and wings, so as to bring everything into proper order, after which she and her mate attended to their young. These particular young ones, only six in number, were fed by their parents 278 times in the course of a day. This was a small wren-family; and if there had been twelve, or even sixteen, as is often the case, what an amount of labour and care the birds must have But they would have been equal to it, and merry all the had! time.

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD