WILLIAM HENRY CLARK

|

|

|

Thus, men of

character

are the

conscience

of the

society to

which they

belong. The

natural

measure of

this power

is the

resistance

of

circumstances.

Impure men

consider

life as it

is reflected

in opinions,

events, and

persons.

They cannot

see the

action,

until it is

done. Yet

its moral

element

pre-existed

in the

actor, and

its quality

as right and

wrong, it

was easy to

predict.

Everything

in nature is

bipolar, or

has a

positive and

negative

pole. There

is a male

and female,

a spirit and

a fact, a

north and a

south.

Spirit is

the

positive,

the event is

the

negative.

Will is the

north,

action the

south pole.

Character

may be

ranked as

having its

natural

place in the

north. It

shares the

magnetic

currents of

the system.

The feeble

souls are

drawn to the

south or

negative

pole. They

look at the

profit or

hurt of the

action. The

hero sees

that the

event is

ancillary;

it must

follow him.

—Emerson. |

|

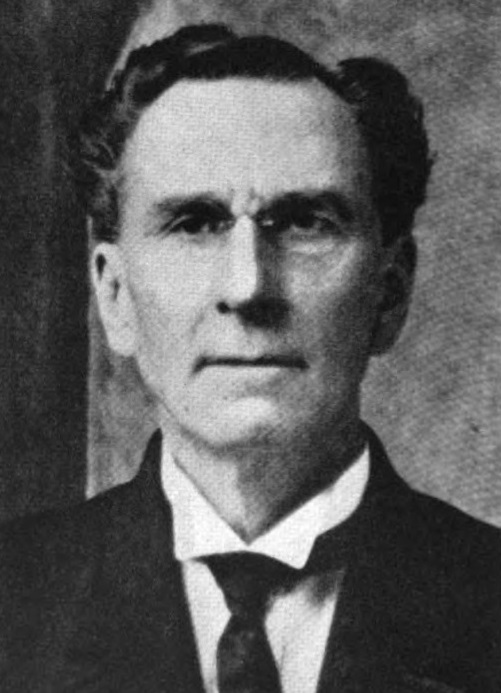

A revival meeting was in progress at the Free Methodist church in Alton, New York. Great conviction was upon the community and many were seeking God. One night the Holy Spirit settled upon the audience with the spell of eternity, as the altar call was being given. A tall young man nineteen years old is at the parting of the ways. As he stands weighing his soul in the balance, Rev. Moses Downing, a veritable son of thunder in early Free Methodism, pointing his finger at him cries out, "Young man, if you don't yield to God, you will go to hell." Recognizing the finger of destiny pointing at him, and the call of eternity summoning, he broke for the altar. That young man was William H. Clark. Later as he continued to pray in the sitting room at home by an old rocking chair, he received the witness that Christ forgave his sins. The conversion of W. H. Clark was similar to that of Charles Spurgeon. Spurgeon as a young man was under deep conviction He says in his unique way, "But of a sudden, I met Moses carrying the law

. . . God's Ten Words . . . and as I read them, they all seemed to join in condemning me in the sight of the thrice holy Jehovah

. . . If I opened my mouth, I spoke amiss. If I sat still, there was sin in my silence. I was in custody of the Law. I dared not plunge into grosser vices: I sinned enough without acting like that. My impression is that this is the history of all the people of God, more or less! . . . in this state, the Bible threatenings are all printed in capitals, and the promises in such small type we cannot make them out." During this period of heavy conviction the young Puritan went to all the churches of Colchester seeking release from his burden. None of the preachers in the large churches helped him Sunday morning on January 6, 1850, found England in the grip of a driving snowstorm. While making his way to a certain church recommended by his mother, the fury of the storm compelled him to turn down a side street. There he entered a little building with the sign "Artillery Street Primitive Methodist Church." About a dozen people were present. The minister, snowbound, failed to appear. A thin-looking layman, a shoemaker or sailor, filled in the gap. The lay preacher was unlearned but he knew God. Taking the text from Isaiah 45:22, "Look unto me and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth," he hammered on one thought -- Looking to Christ for salvation. In about fifteen minutes "he swiftly came to the end of his tether." He observed the distressed face of the boy as he sat alone and pointing his long bony finger at him, shouted in old-fashioned Methodist vigor, "Young man, you're in trouble! Look to Jesus Christ! Look! Look! Look!" And Spurgeon looked, his faith reached out and his burden rolled away. Spurgeon's own account is a classic: "The cloud was gone, the darkness rolled away, and in that moment I saw the sun! Oh, I did 'Look'! I could almost have looked my eyes away! I felt like Pilgrim when the burden of guilt which he had borne so long was forever rolled from my shoulders. I could now understand what John Bunyan meant, when he declared he wanted to tell all the crows on the plowed land about his conversion! "Precious is that wine which is pressed in the wine vat of conviction: pure is that gold which is dug from the mines of repentance; and bright are those pearls which are found in the caverns of deep distress. A spiritual experience that is thoroughly flavored with a deep and bitter sense of sin is of great value to him that hath it. He who has stood before God, convicted and condemned with the rope about his neck, is the man to weep with joy when he is pardoned, and to live to the honor of the Redeemer by whose blood he is cleansed. "I could realize then the language of Rutherford when, being full of the love of Christ, in the dungeon of Aberdeen, he said, 'O my Lord, if there were a broad hell betwixt me and Thee, if I could not get at Thee except by wading through it, I would not think twice, but I would go through it all, if I might but embrace Thee, and call Thee mine!'" Bishop Clark used to relate the severe mental struggle he had over the question of sanctification. When he heard people testify to it, he thought such an experience was impossible, for he had been raised a Calvinist. Yet his heart cried out for it but his head opposed it. Finally he rolled on his bedroom floor crying out for what he thought was impossible. At last his heart and his head got together and he was gloriously sanctified. Charles Wesley's great hymn, "Wrestling Jacob" fits the case of wrestling Clark.

Wilt Thou not yet to me reveal

Thy new, unutterable name?

Tell me, I still beseech Thee, tell;

To know it now resolved I am:

Wrestling, I will not let Thee go,

Till I Thy name, Thy nature know.

My prayer hath power with God; the grace

Unspeakable I now receive;

Through faith I see Thee face to face,

I see Thee face to face, and live!

In vain I have not wept and strove:

Thy nature and Thy name is Love.

His native endowment. He was blessed with good parentage -- the old New York State type of thrift and integrity. He was born at Racine, Wisconsin, April 8, 1854, but his parents were there for only a brief time, and returned to their native state. His father owned a fruit farm near Alton, New York, where the boy was raised near to nature's heart. In him was a blending of English, Scotch, and Irish. His father, Daniel Willis Clark, was of English and Scotch descent, while his mother, Mary Cassidy, was Irish. Before her marriage she was converted from Roman Catholicism and summarily turned out of her home because of her new faith. She died when William was about two years old. The father later married a close friend of his first wife, Mary Lyle, who tenderly cared for the little boy. When he was converted, she told him privately that he would be a bishop some day. His father was a member of the Baptist church until after his son's conversion and entrance into the ministry, when he also joined the Free Methodist Church and served as Free Methodist minister for fifteen years, till superannuated. On August 30, 1877, W. H. Clark was married to Ella Southworth, a daughter of Rev. William Southworth of the Susquehanna Conference. Honored by the conference with an evangelist's license, she was an able speaker, whether in the interest of missions, the Sunday school, or the W.C.T.U. A woman of esthetic nature, she was the soul of poetry and music as well as piety. She composed the words and music for a number of hymns and temperance songs, as well as many poems. She died at Rome, New York, July 9, 1923.

A gentle woman, nobly planned

To warn, to comfort, and command.

Nature was generous in her gifts to Bishop Clark. Possessed of a robust constitution, six feet in height, muscular yet slender, straight as an arrow, he was a man of striking appearance. To see him, one was reminded of the words of Humbolt, "Earth holds up to her master no fruit like the finished man." His face was as striking as his physique. Converted in his youth, he had never gone into the coarse ways of sin which mar the beauty of the human temple. His erect carriage, his face classical in its clear-cut lines, his keen eyes, the window of a noble soul, his courteous, gentlemanly bearing, his grave yet pleasant demeanor, his well-weighed words -- all contributed to produce a living example of a "finished man." An exemplary Christian. Stability was the cornerstone in his life. When he turned his life over to his Lord in 1873 at Alton, New York, he never took it back but pursued God's plan to the end. When the high call came to turn from his own ambitions and preach the gospel, he like Paul conferred not with flesh and blood. The rugged lines of Browning may well apply to him.

Ask thy lone soul what laws are plain to thee,

Thee and no other, stand or fall by them!

This is the part for thee; regard all else

For what they may be, -- Time's illusion.

Shortly after his conversion he joined the Free Methodist Church at Alton. At the sixteenth session of the Susquehanna Conference held at Alton in 1876, he was received on trial under Bishop Roberts. His first circuit was Lansingburg and Bath on the Saratoga District, with Rev. B. Winget as district elder. From that time he went as an obedient servant wherever his conference or the church sent him, always the same exemplary Christian man. Humility beautified his life -- not as an ornament but as an integral part of it. He made little reference to himself in the pulpit or out, but strove to hold up Christ and Him crucified. Whatever position he held in the church was thrust upon him unsought. Before he died he gave careful direction that no eulogy should be pronounced at his funeral. His desire was that the gospel should be preached and Christ exalted. Integrity was stamped upon his countenance and upon the entire range of his life. In the words of Rev. J. T. Logan, "He was too great to descend to anything that savored of self-aggrandizement or self-exaltation or that would not bear the white light of heaven upon it; but was humble and kind; careful and considerate of the interests of others. No one would entertain a doubt as to his sincerity or in the least question his integrity." "His tongue was framed to music, His hand was armed with skill, His face was the mold of beauty And his heart the throne of will." Although cast in a manly mold, his rugged qualities were softened by an esthetic taste which was uncommon. He loved the beautiful whether in the flower of the field, the landscape, or the work of man's hand. While serving as pastor on a certain circuit he used to call at a millinery shop. As he called one day, the milliner had before her the form of a hat she was about to trim. Mr. Clark suggested that he could trim that hat. The challenge was accepted; he trimmed the hat. When he rose to declare his text the next Sunday morning, he saw that very hat, just as he had trimmed it, on one of his leading members in the front seat. Even the dignity of Bishop Clark was ruffled by a rising sense of mirth. This esthetic taste gave him an abiding love for music and poetry, and made him a master of choice language. In the latter half of his life, he received a great spiritual enduement. He was district elder at the time. Not witnessing the results in his own preaching and on the district that he longed to see, and feeling the need of a more fervent spiritual life, he gave himself up for several days to secret self-examination, fasting, and prayer. As a result he received a fresh baptism of the Holy Spirit. The fruits of this experience were manifest to the end of his life in increased humility, augmented spiritual power, and more clear-cut convictions on moral issues. Whereas men generally become more liberal with advancing years, he became more positive on the distinctive lines of separation from the world. Without discrediting what God had done for him in the former years, he emphasized this experience in the light of the experience of Charles G. Finney who held that Christians, and especially ministers, need Pentecostal renewings so positive and powerful as to produce effects like being converted over again. Those who met him in his later years beheld his life luminous with the abiding effusion of this upper-room experience. A royal ambassador of Christ. Bishop Clark was one of God's chosen ambassadors. He needed no credentials to certify to that -- it was self-evident. He bore the marks of the aristocracy of heaven. It was as a preacher of the gospel that he excelled and especially upon the profound theme of the atonement. Of his mastery in the pulpit we will give the verdict of his contemporaries. BY BISHOP SELLEW Bishop Clark's whole life was given to preaching the gospel. He was absolutely devoted to it. He had no side lines, but was unalterably set for the defense and for the propagation of the glorious gospel of Jesus Christ. He was preeminently a preacher. His diction was remarkably clear and smooth, his voice was pleasing, penetrating and powerful, his theology was sound, his logic convincing and his conclusions were irresistible. His whole manner and bearing commanded attention and a respectful hearing in congregations of every caliber and quality. His preaching also had another remarkable quality. Those who had heard him the most were the most eager to hear him again. His preaching never wore out or became threadbare with those who had heard him all his life. The writer presided at a conference in his home town where he had been known all his life, and before he was elected to the office of a bishop, and when he was announced to preach, the church was packed to its capacity. In official administration he was quiet, dignified, pleasing, and popular. All who came in contact with him in an official way not only admired him, but loved him as well. BY REV. O. B. RUSSELL His personal presence notified those he met that he was extraordinary. In form and motion, feature and look he disclosed the fact that he was a mental and spiritual giant. He was genuinely modest. His great nature was adorned with Christ-like humility. He put truth and principle and Christ into the foreground, but said no more about himself than he was compelled to by necessity. His personal achievements would be little known, if the knowledge of them could not be obtained from any other source than his personal mention. His example was a constant reproof to the strut and obtrusiveness of the self-conceited. The items of his faith were not mere chips floating around on the surface of his oceanic mind, but living growths whose roots struck deep into the fertile soil of his great heart. His convictions were inwrought with his life. The truth he thought and felt, he fearlessly declared. Being sincere and fair in his treatment of others, he despised sham and duplicity in low or high, in pew or pulpit. He was ready on the occasion of fitting opportunity to put himself on record against anything he deemed questionable. As a preacher Bishop Clark had few equals. His hearers were impressed with the fact that he had a definite objective towards which he advanced by sound exposition and faultless logic. His sermons increased in depth and force clear through to the end. A text furnishes some preachers simply the topic for a discourse; but in the case of Bishop Clark, it saturated his soul with its truths, and in his stately sentences the whole man spoke the gospel of the Son of God. His noble presence, clear judgment, manifest sincerity, and clean life, gave him unusual influence with his fellows. This is specially true in regard to his home conference, the Susquehanna. Bishop Clark excelled as a doctrinal preacher. His favorite theme was the Atonement. We present a short article, "Easter Assurances" which for its comprehensiveness in small compass would be difficult to surpass: Easter Assurances The literal resurrection of Jesus concludes and consummates the visible processes of redemption, and stands as the final proof of the great truths embraced therein. It attests the claims of Jesus concerning Himself. He declared Himself to be in a unique and superlative sense the Son of God. John 10:36; 14:9. Of this stupendous assertion neither the great truths He uttered, the miracles He performed, nor the prodigies attending His crucifixion afforded final and sufficient evidence. Only the reassumption of His surrendered life could supply the essential visible and moral demonstration, and fulfill His own prophecy. "He was declared to be the Son of God with power, according to the spirit of holiness, by the resurrection from the dead." The resurrection assures the final and eternal dominion of Jesus. As the crucifixion expressed the utmost possibility of vicarious self-sacrifice, so the resurrection manifests the finality of moral triumph. It completes the Savior's personal and racial victory, and assures His everlasting kingship. Through death, Death was destroyed. Heb. 2:14. The vacant tomb completes, attests, and assures the conquest of the cross. By the resurrection "captivity was led captive," his otherwise endless dominion destroyed, and his involuntary captives set at liberty. The "iron gate" opens "of its own accord" before the triumphant victors of redeeming grace. The point of responsibility shifts from the Edenic catastrophe to that of a personal choice. John 3:19. Only those who have trampled emancipation with unhallowed feet will remain in self-determined captivity. The surrendered life of Jesus pays the penalty of transgression, creates a new value available for moral indebtedness, and redeems the last rood of the forfeited inheritance. His supreme exaltation grows out of His self-abnegation. Phil. 2:6-11. His resurrection assures His sovereignty, secures His highest title, "King of kings, and Lord of lords," and with His ascension releases the agencies of regeneration. John 3:5; 16:7-11. The resurrection assures the everlasting dominion of holiness. Sin not only assaults the government, which it would overthrow, but assails the governor, whom it would destroy. God and sin are in irreconcilable conflict. There can be no adjustment of their diverse claims, and no armistice in the struggle. They cannot live together. God must destroy sin, or sin will destroy God. The final contest came at Calvary. Here sin reached the last possibility of daring assumption. The final conquest came on the first Easter morning. The outcome has never since been called in question. Though still contending, Satan acknowledges defeat. "He knows his time is short." The Edenic promise and prophecy (Gen. 3:15) have been fulfilled and hastening events bring near the glory of His return and of the "first resurrection" (Rev. 20:5,6). "A Tribute to Bishop Hart" Illustrates His Choice Diction The world honors its heroes. The memories of great men and great events are fitly preserved in shaft and statue and on history's written page. They constitute an increasingly priceless heritage from the past, without which the world would be poor indeed. Nor has the church less occasion to remember its history and honor its great leaders. God commanded permanent memorials of the miraculous deliverances of His chosen people lest they should pass from the knowledge of the generations yet unborn and the writer to the Hebrews enshrines in imperishable honor the named and unnamed heroes of faith. The departure of great and good men is of more than individual and local interest. Their going enriches the past by the impoverishment of the present and is worthy of more than momentary notice as the links uniting the church that was and the church that is are broken one by one. The passing of Bishop Edward P. Hart removes well-nigh the last personal landmark of early Free Methodist history. His pioneer associates have all preceded him. Among them all none sacrificed more heroically, battled more bravely, or wrought more efficiently than he. To have known him personally is a privilege, and to have listened to his logical, eloquent, and crystal-clear expositions of the great doctrines of Christian faith, an abiding inspiration. In his official relations his clear discernment, quick and sound judgment, and able, impartial, and unvaryingly courteous administration will not be forgotten. He has gone, but his work goes on. The great continuity of life cannot be broken by the passing within the veil. "His works do follow him," and the larger harvest may be gathered from the coming years . . . . The most worthy memorial will be to preserve in its original purity, simplicity and power the church he loved, for which the labors of his early and mature manhood were unstintedly given and whose welfare he still cherishes. Reverently I would place this brief tribute to the memory of the honored man by the imposition of whose hands I was ordained to the Christian ministry and whose acquaintance and example have been during many years and still remain as an abiding inspiration. As one grows older he instinctively feels life more in terms of places and things. This is not placing a materialistic conception upon life, but rather the contrary. Places and things become so closely knit with associations that they symbolize the most sacred experiences of the past. Thus things become saturated with the loveliest and tenderest intimacies of life. Following this urge, men of affairs, after business pursuits have taken them afar, return to the home community or the old homestead to spend their last days. Increasingly Bishop Clark became attached to the home retreat at Rome, New York, in the midst of his books and memories. Near the close of his life he related to the writer how he enjoyed visiting the cemetery and upon bended knee at the grave of his devoted wife pouring out his soul in prayer that it would not be long until his spirit would join hers in the land of endless day. When John Knox, Scotland's great preacher and reformer, was nearing the end his faithful wife asked him if she should not read to him from the Word of God. The dying warrior replied, "Yes, where I first cast anchor." She accordingly read the seventeenth chapter of John containing the great High Priestly prayer of Jesus of which Melanchthon said, "There is no voice which has ever been heard either in heaven or in earth, more exalted, more holy, more fruitful, more sublime, than this prayer offered up by the Son of God." As his physical energy ebbed and his power of speech failed, one of the friends at the bedside cried aloud as to a distant traveler, "John Knox, hast thou hope?" Slowly he lifted his finger and pointed toward heaven. The evidence was conclusive. Peacefully his soul slipped away to his Father's house of many mansions. Shortly before his death, the writer visited Bishop Clark at Rome, New York. How serene and calm he was in the face of death! A few months before he had gone into a state of coma for two or three days. When he regained consciousness he was disappointed to find himself on the earth. He remarked, "I would like to have slipped off quietly to be with the Lord." As he wrote to Rev. F. L. Baker, "I am patiently waiting while the Lord is taking the tabernacle down," and when the last curtain was taken down on Sunday afternoon, November 8, 1925, he pitched his tent in the land where the sun never sets and the leaves never fade. He faced the rising sun with the firm faith of the poet.

"Upon a life I did not live,

Upon a death I did not die,

Another's life, another's death,

I stake my whole eternity."

Rev. B. N. Miner preached the funeral sermon from the text the departed had chosen, "I am the resurrection and the life; he that believeth on me, though he were dead, yet shall he live." He requested no eulogy; he needed none. Forty-nine years of unclouded service as pastor, district elder, the last six as bishop, spoke its own eulogy and reared in human hearts its own memorial. He was laid to rest in Rome, New York, beside the faithful companion of his toils and triumphs, to await the Easter morn of eternity.

|

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD