By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 14 - Modern Discoveries on the Site of Ancient Ephesus

J. T. Wood, F. S. A.

Chapter 6

|

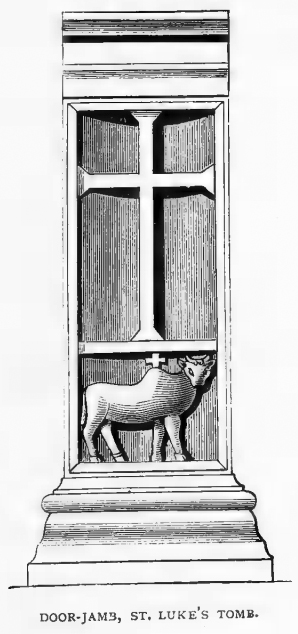

THE CHRISTIAN ANTIQUITIES OF EPHESUS. IN order to understand the ruins of Christian buildings at Ephesus, it is necessary to trace briefly the origin and progress of Christianity in that city. Now we know from Bible testimony that Ephesus was one of the seven cities in Asia Minor, where Christian churches were established in early Christian times; and that even before St. Paul’s conversion, which took place A.D. 36, there were many Christians in these cities, as well as in Judea and Galilee, and in Samaria, in which places we are told the churches had rest on the suspension of that relentless and uncompromising persecution of which Saul of Tarsus had put himself at the head. Paul’s first visit to Ephesus was with Priscilla and Aquila, who accompanied him thus far on his journey from Corinth to Jerusalem; on this occasion, short as his visit was, he went into the synagogue and reasoned with the Jews; but he probably remained at Ephesus only for a single day, or only during the short time that the vessel he sailed in discharged part of its cargo. (See Acts xviii. 18-28 and ix. 31.) The nineteenth chapter of the Acts gives a most graphic and interesting account of St. Paul’s success at Ephesus during a sojourn of nearly three years; he taught Christianity in the synagogue of the Jews, and in the school of one Tyrannus; his teaching convinced many, and even they who practised as magicians, and so obtained their livelihood, brought their books together and burnt them publicly; this took place probably in the forum, on one side of which is the great theatre, where the disturbance took place, which arose from the fears of Demetrius, the maker of silver shrines for the temple of Diana. So great was the tumult, and such were the fears for St. Paul’s safety, that he was persuaded by his friends, as well as by some of the chief men of the city, not to enter into the theatre, and he was obliged to leave Ephesus immediately after. On the departure of St. Paul, Christianity probably received a severe check by a reaction in favour of the worship of Diana; great indeed must have been the enthusiasm of her worshippers ' who cried out, for the space of two hours, ‘Great is Diana of the Ephesians!’ for they were not even inspired by the sight of the temple itself, as it was not visible from the theatre. The long Salutarian inscription found on one of the walls of the southern passage into the theatre, and which was inscribed in the time of Trajan, about A.D. 104, describes in detail a number of these shrines, probably similar to those made by Demetrius and his fellow-craftsmen. The shrines described in this inscription, and numbering more than thirty, were of gold and silver, weighing from three to seven pounds each, and represented figures of Artemis with two stags, and a variety of emblematical figures; these were voted to Artemis, and were ordered to be placed in her temple. This inscription bears interesting testimony to the truth of the particulars recorded in the Acts, as well as to the popularity of the worship of Artemis about half-a-century after St. Paul’s departure. As numerous decrees of the council and the people were found in the excavations at Ephesus, it is very probable that a decree was issued after the disturbance in the theatre, forbidding the preaching of the Gospel by St. Paul and others; and this may account for St Paul’s afterwards passing on to Miletus, without touching at Ephesus, on the occasion of his next visit to Jerusalem. Eusebius, writing in the fourth century, tells us that St. Luke was born at Antioch in Syria, but he does not say in what condition of life; he is described by St. Paul as Luke the beloved physician; but this might have been an appellation bestowed upon him as a distinction for some knowledge, however slight and superficial, of the practice of medicine. We first hear of him in the New Testament1 when he joins St. Paul at Troas, and accompanies him into Macedonia. St. Luke, who was the writer of the Acts of the Apostles, suddenly adopts the use of the first person plural in chapter xvi., the inference being that he then joined company with St. Paul at Troas. He thus journeyed as far as Philippi, and on St. Paul leaving that place, St. Luke resumes the use of the third person; St. Luke, therefore, might either have remained at Philippi, or might have proceeded to some other place. In chapter xx. 5, we are informed that St. Luke again joined St. Paul’s company at Philippi; but it is doubtful whether he had remained there during the whole seven years of St. Paul’s absence, viz. from A.D. 51-58. St. Luke accompanied St. Paul through Miletus, Tyre, and Cęsarea to Jerusalem. The last we hear of him in the New Testament is that he accompanied St. Paul to Rome.2 The Greek Menza says that he lived to the age of eighty. Epiphanius says that he preached in Dalmatia, Gaul, Italy, and Macedonia. Gregory Nazianzen makes Achaia the theatre of his preaching. Gaudentius, Bishop of Brescia, writing in the fifth century, spoke of St. Luke as a martyr, and says that he suffered at Patras. One of the most interesting buildings associated with Christianity in Ephesus is the so-called tomb of St. Luke, which I suppose was contemporaneous with the earliest predominance of Christianity at Ephesus, and with some of the churches, the remains of which are to be found within the city. The building which I presume is the tomb of St. Luke, is of white marble, circular on plan, and 50 feet in diameter; it was adorned by sixteen columns, which were raised upon a lofty basement, a large portion of which remains in situ, as well as one of the door-posts, upon the front of which were carved two panels; the upper one contains a large cross, the lower one the figure of a bull or buffalo of the country, with a small cross over its back. On the side of the same door-post there are the remains of the figure of a man, which has been almost entirely chopped away; the nimbus, however, which encircled or surmounted the head, having been incised, remains perfect, and this figure is perhaps of itself sufficient evidence that this building was the tomb or shrine of a saint or martyr; and the bull, being the emblem of St. Luke, informs us what saint was represented by the figure; the opposite door-post had a large cross in a sunk

panel. I have supposed that this building was of the latter end of the third or beginning of the fourth century, and I presume that the early Christians of that time were allowed to remove the remains of St. Lake from their original burial-place outside the city to this place of honour within the city; it would not be an ancient tradition, little more than 200 years, and the saint’s first burial-place would be well known to the early Christians. The building, moreover, stood within a quadrangle more than 150 feet square, which was surrounded by a portico, and was paved with thin marble slabs, under some of which were found graves; these I take to be a further proof of the nature of the building which they surrounded; they were probably Christian graves, and it is well known that the early Christians would pay large sums of money for the privilege of being buried near a saint or martyr. At the time that I discovered this tomb, I was anxious to obtain historical proof of St. Luke's death at Ephesus, and for this purpose I sought an interview with the Greek Archbishop of Smyrna, who, in reply to my inquiries, took down the books of two ancient Greek writers, one of whom related that St. Luke was hung at Patras, the other that he died at Ephesus; I unfortunately took no note of the names of the writers, and I have not since been able to find any account of St. Luke’s death at Ephesus. There seems to be no authentic account extant of St. Luke’s life after his sojourn at Rome, or of the place or manner of his death. It seems not unlikely, with the evidence now before us, that he might have ended his days peacefully at Ephesus, and that he was buried outside the city, and that his remains were removed and entombed as I have suggested; but even if he had died at Patras, his remains might have been removed to Ephesus. It has been argued that this building might have been a pagan monument originally, adapted in later times as a Christian shrine; that the figure of the bull or buffalo is to be seen on coins of Asia Minor; that the building might have been a polyandrion; but the style of the architecture, which is certainly not earlier than the latter end of the third century, is sufficient to prove to the contrary. We now come to the churches, remains of many of which may now be seen at Ephesus. The most remarkable of these is the double church on the north side of the forum. Each church consisted simply of a long nave, which was terminated by an apse at the east end; this was flanked by two chambers, which were probably the prothesis and diaconicum. I have supposed that this church might have been erected as early as the beginning of the fourth century, or even earlier. The edict of Diocletian, which is attributed to the year 302, ordering the destruction of churches, proves that such buildings then existed. Basilicas, or halls of justice, we know, were converted into churches, and churches were built after the same model. There are remains of two other churches within the city: one of these is near the tomb of St. Luke, and might have been dedicated to him; the other is on the side of the mountain on the south side of the forum; of this little remains beyond the apsidal end. The rock-cut church on the east side of Mount Coressus is outside the city, and is said to have been dedicated to the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus. The whole of this church is cut out of the solid rock, excepting only the roof and a portion of the east wall. Considerable remains of a church were found in excavations on the hill at Ayasalouk: this was, perhaps, St. John’s Church, and was in existence when the Council of Bishops assembled in the year 431 A.D. A cathedra, or raised marble seat for the presiding bishop, was found in its original position. Over these remains the Greeks built a church during the time I was carrying on my work, and Sundays and Saints’ days were duly observed. In following the road between the Magnesian gate and the temple, I discovered many large marble sarcophagi, several of which had the labarum, shown on p- 39, and other Christian emblems cut upon their covers; some of these, judging from the style of the inscriptions, were probably of the fourth century. In these sarcophagi nothing but skeletons were found. In the same road a Christian tombstone of a peculiar character was found. It consisted of a large cross, with a female figure behind it, the head of the figure appearing above the cross, and the drapery flanking it on both sides. A Christian tomb, composed of thin marble slabs, was found in excavations on the hill at Ayasalouk; the characters of the inscription prove that it was as late as the seventh or eighth century. A hoard of coins found under the Turkish pavement over the site of the temple had amongst them a number with this legend on the obverse, Moneta que fit in Theologo, and a seated figure of the Seljuk Saroukhan, holding an orb and sceptre; these must date from 1342 — 1389. On the reverse is a floreated cross, surrounded by the legend De mandato Domini ejusdem loci. Ayasalouk therefore derived its name from St. John, or Ἄγιος Θεολόγος. A number of the coins found here were issued by the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, established at Rhodes, into whose hands Ephesus and Ayasalouk fell in the fourteenth century. I found the cross cut on the posts of the Magnesian gate, and on most of the public buildings in the city. I also found on the piers of a gateway in front of the Great Theatre these short Greek inscriptions — Χριστιανῶν βασιλέων πρασίνων πολλὰ τὰ ἔτη Εὐσεβέων βασιλέων πολλὰ τά ἔτη Of the Christian Emperors of the Greek faction, may the years be many. Of the pious emperors, may the years be many.

|

|

|

|

|

1) Acts xvi. 10. 2) Acts xxviii. 11-16.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD