By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book # 14 - Modern Discoveries on the Site of Ancient Ephesus

J. T. Wood, F. S. A.

Chapter 3

|

DISCOVERY OF THE SITE OF THE TEMPLE OF DIANA. THE temple of Diana (Artemis) at Ephesus ranked as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, and is alluded to, not only by many ancient writers, but in a special manner in the Acts of the Apostles. The remains of the famous temple, deeply buried, and thus hidden from the eye of man for so many centuries, became a subject of great curiosity during the last and present centuries, travellers having only the vague descriptions of the temple and its site by ancient writers. The firman, which was procured for me from the Sublime Porte by the British Government, permitted me to excavate for antiquities at Ephesus and Colophon, and allowed me to export all the antiquities I might find excepting duplicates: these latter must be left for the Ottoman Government. These terms were so advantageous, that Mr. Blunt, the English Consul at Smyrna at that time, in writing to inform me that the Pasha had sent him word that the excavations might be resumed after a temporary suspension, added that he merely requested that when Mr. Wood had found the temple of Diana in duplicate he would wish to be informed of at! The suspension here alluded to was caused by the intrigue of a certain colonel, Réchad Bey, who was persuaded by a Greek, who had dreamt of treasure at Ephesus, to seek for it in one of my excavations. This man had sufficient influence with the Pasha of Smyrna to stop my works, while he sought for the hidden treasure by blowing up some of the ancient masonry of the Great Gymnasium with gunpowder. My firman obliged me to obtain the leave of the owners of the land on which I wished to excavate; but I ventured to disregard this sometimes, and dug away without hindrance, excepting in one instance, where the land-owner came forward, and positively forbade my excavations on any part of his land. I had afterwards reason to believe that most of these men had no real right to the land they claimed, and had not purchased it from the Government. For the first four months I explored the ground to the west and north of the city, and I found little more than the remains of Roman and Medieval buildings. For the whole of September the excavations were nearly suspended in consequence of an unfortunate accident I met with in riding home one night from an expedition to Ninfi to see the famous rock-cut figure of Sesostris. My horse fell with me into a deep dry ditch, and the result was the fracture of a collar-bone. During my absence the men did very little work, and nothing of consequence was found; it was, however, more or less consolatory that there was so much less ground to be explored. Ten months passed away, and the solution of the great problem as to the site of the temple seemed to be as far off as ever. In addition to the numerous trial holes which I had sunk over a large area of the plain, I made some excavations at the Great Gymnasium at the head

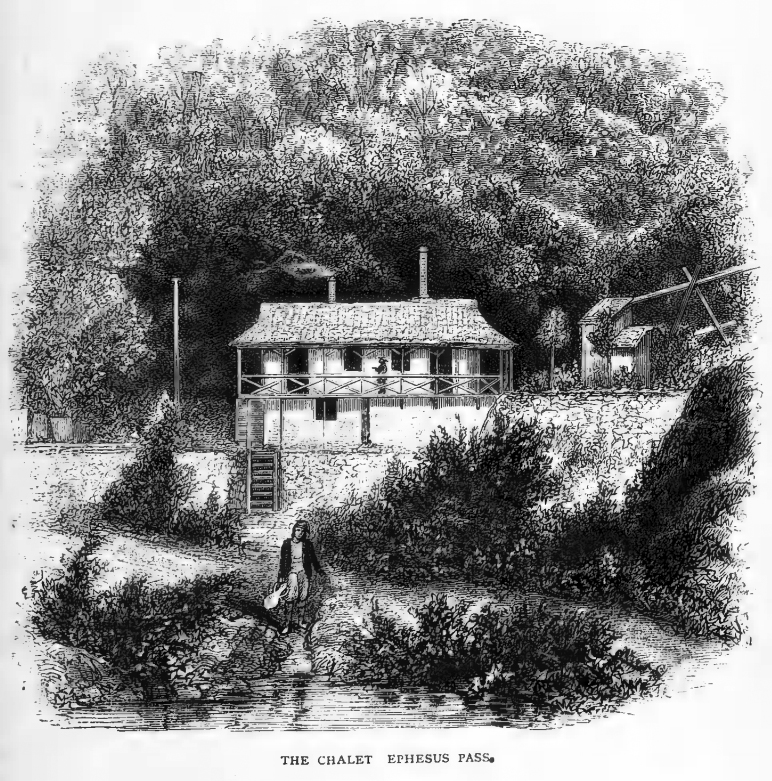

of the city port, which had often been regarded by travellers as the temple itself. A number of monolithic granite shafts of columns here lie prostrate, and the columns in St. Sophia at Constantinople, which are there pointed out as columns from the temple of Diana at Ephesus, were taken, I believe, from this building. In front of it I discovered a large marble hall of good Roman design, which I cleared out and found perfectly intact; one side of the building gave way one day immediately after I had visited it. In March, 1864, Mr. Newton (now Sir Charles Newton, K.C.B.), late Keeper of the Greek and Roman Antiquities in the British Museum, came to Ephesus. At that’ time it had occurred to me that the best way to find the temple would be to find one or two of the ancient gates of the city, outside which I might perhaps find a well-worn road which might lead to the temple. As the position of the gates could not be determined without extensive excavations, it was decided that Mr. Newton should recommend the Trustees of the British Museum to grant me £100 for the exploration of the Odeum. I had wished to explore the Great Theatre, in the hope that I might meet with some inscription, or some other indication of the position of the temple. It was, however, decided that the Odeum should first be explored, and I set to work with renewed energy with the small grant of the Trustees. As I was much engaged at Smyrna at that time as an architect, I appointed a young Greek to superintend the works. This man was highly intelligent, but very dishonest. Fragments of a large statue of Lucius Verus were found near the central doorway of the Odeum. The lower part of the body, with the legs and thighs complete, arrived safely at the British Museum. The torso was put on board a sailing vessel at Smyrna bound for England; the vessel was wrecked, and the torso was | no more seen. A figure of the muse Erato was rescued, but was so much damaged by the action of the sea, that it was decided not to claim it from Lloyd’s agent at Syra, so it remains there to this day. Another piece of sculpture found in the Odeum was a life-size figure of Silenus with the phallus in a patera. Besides the statuary here mentioned were found numerous fragments of four inscriptions on thin slabs of marble, which had been fixed upon the walls of the proscenium, and had fallen upon the pulpitum. These were rescripts of letters from the Emperors Hadrian and Antoninus Pius to the Magistrates, Council, and people of Ephesus. One of the letters from Antoninus reproaches the people of Ephesus for their want of appreciation of a certain Vedius Antoninus, who had suggested great improvements in the city, of which the emperor approved. I cleared out the whole of the Odeum, and found the whole of the seats and steps, also the marble pavement of the orchestra and pulpitum, quite perfect; but visitors of all nations have since made sad havoc of what remained, and it is now in a sadly ruinous condition. The fluted columns of the proscenium, with their beautifully carved Corinthian capitals, had fallen on the pavement, and little more than pedestals with portions of the five doorways remained in position. This theatre was 153 feet in diameter, and was capable of seating 2,300 persons. While I was carrying on these excavations, I had obtained permission from the railway authorities to occupy a small chalet in the Ephesus Pass — this was about three miles from the Odeum. I had at that time only one cavass as general servant and body-guard. My home was in a lonely spot, and when I first took possession of the châlet a gang of robbers had broken into one or two of the few houses within a mile of me,

had tied the residents to their heavy furniture, and made off with plunder; I ran the risk of being similarly treated, my greatest danger being when I returned in the evening with my single attendant, and while he went down to the stream to fetch water, I was left alone on the balcony; the house was built on a steep slope, which was covered with thick underwood, most favourable for an ambush. As I walked up and down on the balcony I kept on the alert against sudden attack, and I never dined without a pistol on the table ready to my right hand; these precautions could be seen from a side window, and very likely warned off the robbers, and I was not attacked during the few months during which I occupied the chalet. One evening on walking home from the Odeum my foot struck against a stone, which, on examination, I found showed the head of a cross; the next day I had the whole stone laid bare, and found that it was a doorjamb, on the front of which were two panels, in one of which was carved a large Latin cross, and in the other the figure of a bull with a small cross above its back; on the side of the stone there had been carved a human figure, of which nothing remained but the auriole which had encircled the head; this having been incised, remained perfect. I concluded from these signs that this must have been the tomb of St. Luke, who, according to tradition, is said to have died and to have been buried at Ephesus. This tomb is fully described in a subsequent chapter. One afternoon, while I was clearing out the Odeum and St. Luke’s tomb, and while I was actually employed in superintending operations at the latter, myganger, a tall dark Italian, came breathless and hatless to tell me that some Zébecks had come to the Odeum; they had stolen a sheep, and had come to look for me; he urged me to get away with as much speed as possible. I did not know whether I should believe him or not, and hesitated to start homeward in precipitate haste. I was inclined to think it might be a hoax and trial of my courage; and while I hesitated, one of the workmen (a Greek) urged my taking flight at once, and he advised me to leave my watch and money in ‘a nice little hole’ which he would dig for me, and in which they would be perfectly safe! I need scarcely say I did not trust my valuables in the snug ‘little hole,’ nor did I leave the spot till I could do so with becoming dignity; for to have shown the white feather would have been bad policy. As the Zébecks did not come on to the place where I awaited them, I was inclined to think that my ganger’s tale was indeed a hoax; if so, he acted his part admirably. The interesting discoveries made at the Odeum encouraged the Trustees of the British Museum to make me a special grant to explore the Great Theatre; but I was not then permitted to spend any money in a manner more direct upon my main enterprise — the discovery of the Temple of Diana. In February, 1866, I commenced the exploration of the Great Theatre. It was built against the steep western side of Mount Coressus. Its diameter, 495 feet, was measurable before the excavations were commenced. The pulpitum was twenty-two feet deep, the orchestra 110 feet in diameter. This theatre was capable of seating 24,500 persons. The proscenium, which was handsomely decorated with two tiers of columns, had fallen upon the pulpitum (stage); in clearing the pulpitum and orchestra of the débris which encumbered them, I found a great number of inscriptions, mostly Greek, and built into the masonry of the proscenium. I found six large blocks of marble, on which were inscribed twenty-six decrees of the Senate and the people of Ephesus, conferring the citizenship and other honours upon various persons.. One of the most interesting of these decrees is one conferring the citizenship upon a certain Rhodian named Agathocles, who had in time of dearth sent into the market 14,000 measures of wheat, to be sold at a low price. The Essenes were to allot him a place in a tribe and a thousand. The decree was ordered to be inscribed in the Temple of Artemis. Another of these interesting decrees is thus worded: — ‘Philenetus, son of Philophron, moved, That whereas Nicagoras, son of Aristarchus of Rhodes, when sent from Kings Demetrius and Seleucus to the people of Ephesus and the other Hellenes, appeared before the people, and addressed them on the friendly relations which have been established, and on the good-will which the kings continue to bear towards the Hellenes, and renewed the alliance which formerly existed between himself and this city: it be hereby resolved by the council and the people to commend Nicagoras for the good-will which he continues to bear towards the kings and the people, and to crown him with a crown of gold, and to proclaim the crown in the theatre at the Ephesian festival, and further, to grant citizenship to him upon equal and similar terms as to the rest of their benefactors, and that he enjoy the privilege of occupying a front seat at the games, and of entering or leaving the harbour at pleasure alike in war and peace, and of exemption from duty on all goods which he may import or export, whether for his own family or for market, and of admission to the assemblies of the council and the people first after the sacred rites. These distinctions to belong to himself and to his descendants. Moreover, that the grants which have now been made to him be inscribed by the temple wardens where they inscribe other like grants, and that they allot him a place in a tribe and to a thousand, to the end that all may know that the people of Ephesus honour with appropriate gifts those who are loyal to their interests. And also that the people send him pledges of their friendship. Admitted into the Ephesian tribe, and the Lebedian thousand.’ These decrees could not have been of later date than 299 B.C., and the blocks of marble upon which they are — inscribed must therefore have come from the temple which succeeded that which was destroyed by Erostratus on the day when Alexander was born, B.C. 356, and were evidently conveyed to the theatre to aid in the reconstruction of the proscenium. On further exploration of the theatre it is probable that more of these interesting decrees would be found. On clearing out the southern entrance to the theatre, there was laid bare a long inscription which covered the wall terminating the auditorium. It was inscribed on massive blocks of marble, which were strongly dowelled together. We had the greatest difficulty in taking them from the wall without injury. Seeing the difficulty, and the rough and ready manner in which the blue-jackets, who were employed at that time upon this part of the work, went to work, I promised them a pound of tobacco all round if they would work more carefully and. bring one of the most important of these stones down upon the pavement. This promise had the desired effect, and the stone was taken from the wall without injury. The removal of another large block, which was not of the same importance, was accomplished by allowing it to come down with a loud thud. The blue-jackets were sent out to Ephesus to remove the stones which I had ready for conveyance to the British Museum. H.M.S. Terrible, Captain, now Admiral Sir John Commerell, was sent to Smyrna at my request for a ship of war, to take the antiquities to England, and twenty-six of the crew were sent out to Ephesus. These men at first began to chip a sarcophagus, but on my remonstrating and reminding them that they had been sent out to assist me, and not to destroy what had been found, they at once desisted, and they never again gave me reason to complain during the twenty days they were employed under my direction. The inscription above mentioned described a number of gold and silver images, weighing from 3 lbs. to 7 lbs. each, which were voted to Artemis, and were to be placed in her temple; and on certain days of assembly in the theatre, including the anniversary of the birthday of the goddess, they were to be carried from the temple to the theatre by two curators of the temple attended by the conquerors in the games and a staff-bearer and guards. This procession was met at the Magnesian gate by the Epheboi (young men), who assisted to carry the images into the theatre, where they were set up in full view of the assembly. After the assembly the images were carried back to the temple through the Coressian gate, to which gate the young men assisted in carrying them. The inscription mentions all the details of the endowment, even the sum of money to be spent in plate-powder for cleaning the images. The images themselves are minutely described, and their individual weight in pounds, ounces, and grains.

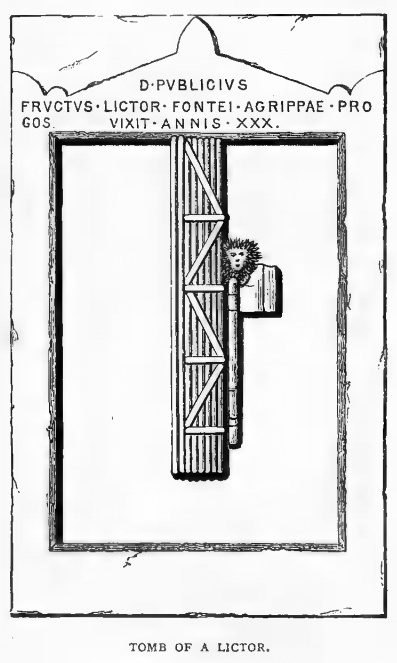

One inscription was a most important discovery. It confirmed me in the plan I had already revolved in my mind, whether I should not find one or more of the gates of the city, and by a well-worn road, which I hoped to find outside the gate, work my way on to the temple. Two gates are named in the inscription, the Magnesian and Coressian gates. I now obtained leave to spend £50 of my grant in my search for the temple, and with that sum I succeeded in finding both these gates. At the Magnesian gate, which had three openings, two for carts and chariots and one for foot-passengers, deep ruts in the marble pavement remain at and near the gate; these ruts are not traceable far outside the gate, and in tracing their ultimate direction, I had to open a large area. I here found a record of the river Marnas, the water of which was brought in at this gate. I eventually found a marble paved road, thirty-five feet wide, turning northward round Mount Coressus with four distinct chariot-ruts deeply cut in it; at the same time I followed the road turning southward for about 200 yards which showed very little traffic, and it evidently was the country road leading to Magnesia ad Mzandrum. On both sides of this road were found some very interesting tombs and cippi, one of which was inscribed to the memory of a soldier of the Roman army aged twenty-six. Another, of which I give an engraving, was that of D. Publicius Fructus, a lictor. It is a small panel on which are carved the fasces, and an axe surmounted by the head of Terror (Φόβος) As I decided now to follow the road leading round Mount Coressus, I devoted all my energy to tracing its course up to the precincts of the temple; and I was duly authorized to devote the rest of my grant to its discovery, with a warning that I should have no more if I did not with it find the temple. At a short distance from the Magnesian gate I found the remains of the portico built by a rich Roman named Damianus in the second century B.C. This portico, vaguely described by Philostratus in his Lives of the Sophists, was intended to shelter people going from the city to the temple, and it ran alongside the road. We are here reminded of the porticoes or covered ways at Bologna and Vicenza leading to churches outside the gates. I confined my excavations to one side of the road, and laid bare a great number of tombs and marble

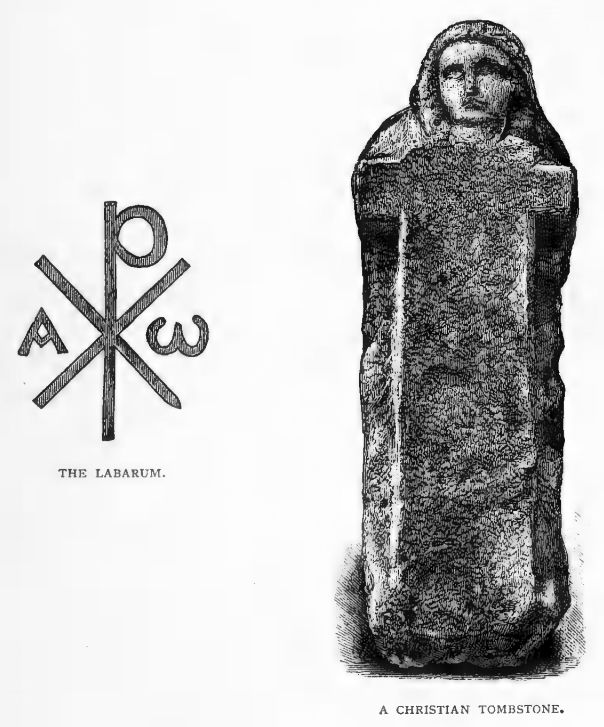

sarcophagi; one of the latter contained the remains of fourteen persons, another those of four persons, one or two had the labarum cut upon their limbs. At the distance of 2,600 feet from the Magnesian gate were found remains of what I presume must have been the tomb of Androclus. Pausanias describes this tomb and the temple of Jupiter as being on the road from the Magnesian gate to the temple. Six hundred feet beyond the tomb of Androclus I found the road I had been searching for leading off at right angles towards Ayasalouk. This road was forty-five feet wide, ten feet wider than the road I had been following, and it had handsome sarcophagi on each side. Atthe time I found this road, I had nearly come to the end of my grant, and the barley had grown up to its full height, about eight feet. I had no means of compensating the land-owners if I cut down the barley; but tracing the direction of the road by taking advantage of one or two boundaries which crossed it at | right angles, I saw that it pointed to a modern boundary, marked by some old olive-trees and bushes of the Agnus Castris, which had long before attracted my attention. I now determined to put on a dozen men at this point, and make a more extensive excavation. This resulted in the discovery of a thick wall of rough masonry. Extending the excavation, I struck upon the angle of the wall, and at about eight feet below the surface, laid bare two inscriptions on the south side which were repeated on the west side. These inscriptions showed that I had discovered the peribolus wall of the temple described by Tacitus, which was built by Augustus to restrict the temenos or sacred precinct which had approached too near the city and facilitated the escape of the wrongdoer. This important discovery was made on May 2, 1869. The search for the temple had commenced on May 2, 1863; and consulting my diaries I found that during this long period I had worked on my enterprise for twenty months. The day on which this wall with the inscriptions was found terminated the long period — six years — of great anxiety and misgiving, and of almost hopeless endeavour; and the discovery now made compensated for all. M. Waddington, afterwards French ambassador in London, wrote thus to congratulate me on the discovery of the peribolus wall: — ‘I congratulate you most warmly on your most important discovery, the more so because it is not the result of a lucky accident, but entirely due to your wonderful perseverance and tenacity under difficult and sometimes dangerous circumstances.’ I traced the peribolus wall for 1,000 feet northward and 500 feet eastward, and thus fully confirmed the information given by the inscriptions that it enclosed the Artemisium and Augusteum, from the revenues of the former of which the wall was built. The masonry of this was very rough, and was probably contract work. In order to make this discovery complete, I had been obliged to apply to the Trustees of the British Museum for an additional sum of £200; and this was granted in consideration of the sacrifices I had made, and my perseverance under much discouragement in carrying on the work of exploration. While digging at the theatre, I found on the east side of the forum a basin of Breccia fifteen feet in diameter; which, from its form and from there being no hole in the centre, I concluded must have been used as a font for the public baptism of the early Christians. The basin was mounted upon a pedestal, and the sunk part of it was capable of accommodating twenty persons at a time. The centre was raised, to enable the baptizer to stand dry-shod. A cistern and water-pipe were found near. To the south of the Great Theatre, and overlooking the Agora, I found the remains of a portico with a beautiful Roman mosaic pavement, of varied design, nearly intact.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD

There were several images of Artemis of gold, with

two silver deer, two silver figures of Artemis bearing a

torch; there were also silver images representing the

senate, the council, the equestrian order, the Roman

people of Ephesus, the elders, the young men and the

city of Ephesus; also a libation vessel (patera), also a

silver image of the Euonymiantribe. There were doubtless images representing all the tribes, but their names

are lost in the lacunz of the inscription.

There were several images of Artemis of gold, with

two silver deer, two silver figures of Artemis bearing a

torch; there were also silver images representing the

senate, the council, the equestrian order, the Roman

people of Ephesus, the elders, the young men and the

city of Ephesus; also a libation vessel (patera), also a

silver image of the Euonymiantribe. There were doubtless images representing all the tribes, but their names

are lost in the lacunz of the inscription.