Nineveh and Its Remains

Volume 2

By Austen Henry Layard, ESQ. D.C.L.

Part 1 - Chapter 13

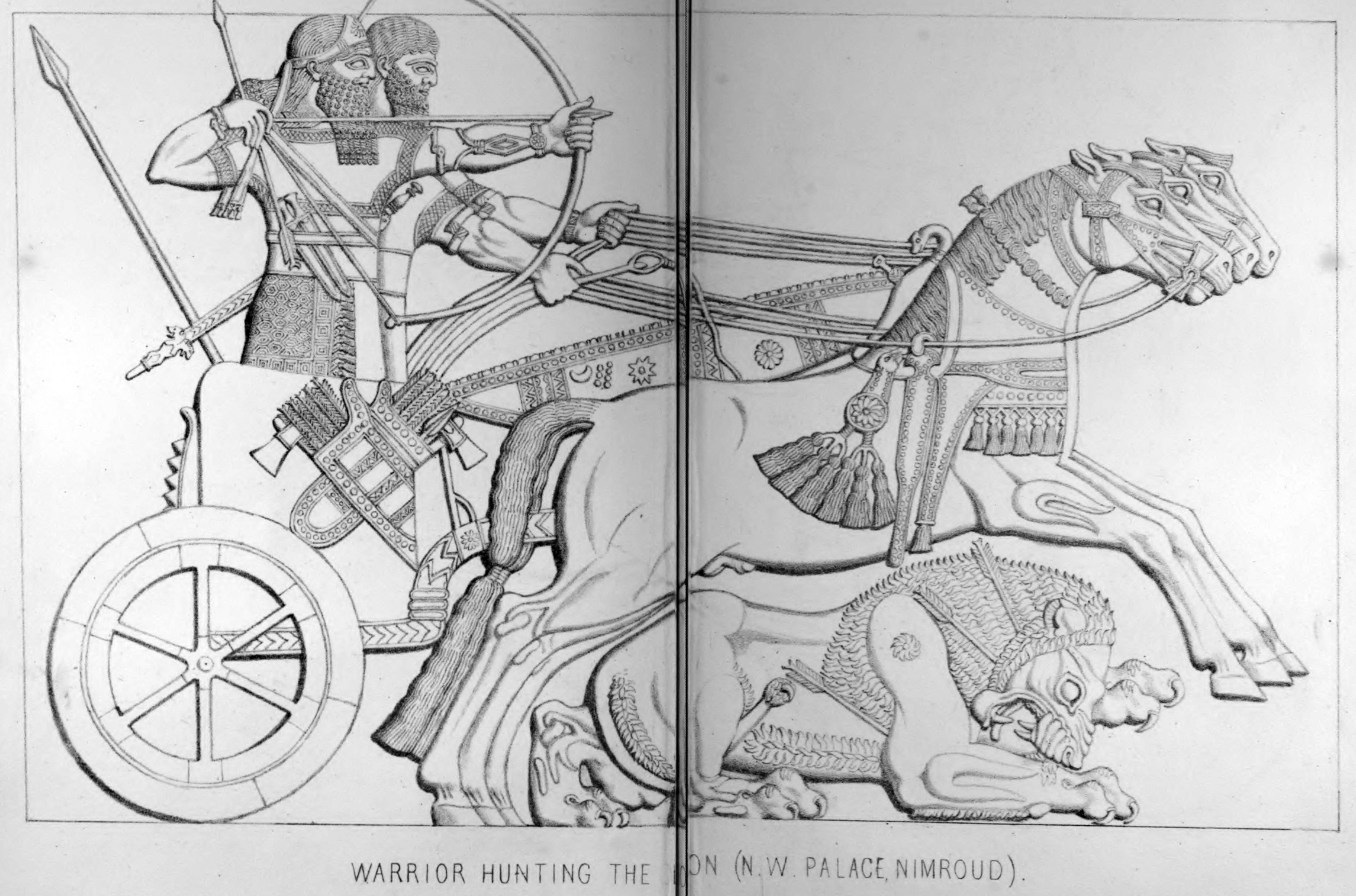

ASSYRIA PROPER, like Babylonia, owed its ancient fertility as much to the system of artificial irrigation, so extensively and successfully adopted by the inhabitants of the country, as to the rains which fell during the winter and early spring. The Tigris and Euphrates, unlike the Nile, did not overflow their banks, and deposit a rich manure on the face of the land. They rose sufficiently at the time of the melting of the snows in the Armenian hills, to fill the numerous canals led from them into the adjacent country; but their beds were generally so deep, or their banks so high, that when the stream returned to its usual level, water could only be raised by artificial means. The great canals dug in the most prosperous period of the Assyrian Empire, and used for many centuries by the inhabitants of the country — probably even after the Arab invasion — have long since been choked up, and are now useless. When the waters of the rivers are high, it is still only by the labour of man that they can be led into the fields. I have already described the rude wheels constructed along the banks of the Tigris. Even these are scarce. The government, or rather the local authorities, levy a considerable tax upon machines for irrigation, and the simple buckets of the Arabs become in many cases the source of exaction or oppression. Few are consequently bold enough to make use of them. The land, therefore, near the rivers, as well as that in the interior of the country out of the reach of the canals, is entirely dependent upon the rains for its fertility. Rain, amply sufficient to ensure the most plentiful crops, generally falls during the winter; the grain, in the days of Herodotus, yielding two and even three hundred fold. Indeed, such is the richness of the soil of Assyria, that even a few heavy showers in the course of the year, at the time of sowing the seed, and when the corn is about a foot above the ground, are sufficient to ensure a good harvest.1 It frequently, however, happens that the season passes without rain. Such was the case this year. During the winter and spring, no water fell. The inhabitants of the villages, who had been induced to return by the improved administration and conciliatory measures of the late Pasha, had put their whole stock of wheat and barley into the ground. They now looked in despair upon the cloudless sky. I watched the young grass as it struggled to break through the parched earth; but it was burnt up almost at its birth. Sometimes a distant cloud hanging over the solitary hill of Arbela, or rising from the desert in the far west, led to hopes, and a few drops of rain gave rise to general rejoicings. The Arabs would then form a dance, and raise songs and shouts, the women joining with the shrill tahlehl. But disappointment always ensued. The clouds passed over, and the same pure blue sky was above us. To me, the total absence of verdure in spring was particularly painful. For months my eye had not rested upon a green thing; and that unchanging yellow, barren, waste, has a depressing effect upon the spirits. The Jaif, which the year before had been a flower garden and had teemed with life, was now as naked and bare as a desert in the midst of summer. I had been looking forward to the return of the grass to encamp outside the village, and had meditated many excursions to ancient ruins in the desert and the mountains; but I was doomed to disappointment like the rest. The Pasha issued orders that Christians, as well as Mussulmans, should join in a general fast and in prayers. Supplications were offered up in the churches and the mosques. The Mohammedans held a kind of three days Ramazan, starving themselves during the day, and feasting during the night. The Christians abstained from meat for the same length of time. If a cloud were seen on the horizon the inhabitants of the villages, headed by their mullahs, would immediately walk into the open country to chant prayers and verses from the Koran. Sheikhs — crazy ascetics who wandered over the country, either half clothed in the skins of lions or gazelles, or stark naked — burnt themselves with hot irons, and ran shouting about the streets of Mosul. Even a kind of necromancy was not neglected, and the Cadi and the Turkish authorities had recourse to all manner of mysterious incantations, which were pronounced to have been successful in other parts of the Sultan's dominions on similar occasions. A Dervish returning from Mecca, had fortunately brought with him a bottle of the holy water of Zemzem. He offered it, for a consideration, to the Pasha, declaring that when the sacred fluid was poured out in the great mosque, rain must necessarily follow. The experiment had never been known to fail. The Pasha paid the money, — some twenty purses, — and emptied the bottle; but the results were not such as had been anticipated; and the dervish, when sought after to explain, was not to be found. There was no rain, not even the prospect of a shower. A famine appeared to be inevitable. It was known, however, that there were abundant supplies of corn in the granaries of the principal families of Mosul; and the fact having been brought to the notice of the Pasha, he at once ordered the stores to be opened, and their contents to be offered for sale in the market at moderate prices. As usual, the orders were given to the very persons who were speculating upon the miseries of the poor and needy — to the cadi, the mufti, and the head people of the town. They proceeded to obey, with great zeal and punctuality, the orders of his Excellency; but somehow or another overlooked their own stores and those of their friends, and ransacked the houses of the rest of the inhabitants. In a few days, consequently, those who had saved up a little grain for their own immediate wants, were added to the number of the starving; and the necessities and misery of the town were increased. The Bedouins, who are dependent upon the villages for supplies, now also began to feel the effects of the failure of the crops. As is generally the case in such times, they were preparing to make up for their sufferings by plundering the caravans of merchants, and the peaceable inhabitants of the districts within reach of the desert. Although early in the spring, the Shammar and other formidable tribes had not yet encamped in the vicinity of Mosul; still casual plundering parties had made their appearance among the villages, and it was predicted that as soon as their tents were pitched nearer the town, the country without the walls would be not only very unsafe, but almost uninhabitable. These circumstances induced me to undertake the removal of the larger sculptures as early as possible. The dry season had enabled me to carry on the excavations without interruption. As no rain fell to loosen the earth above the ruins, there was no occasion to prop up the sides of the trenches, or to cover the sculptures: considerable expense was thus saved. Had there been the usual violent storms, not only would the soil have continually fallen in and reburied the building, but the bas-reliefs would have been exposed to injury. A marsh would also have been formed round the base of the mound, completely cutting me off from the river, and impassable to any cart carrying the larger sculptures. My first plan, when anticipating the usual wet weather, was to wait, before moving the bas-reliefs, until the rain had completely ceased, and the low ground under the mound had been dried up. I could not, in that case, commence operations before the month of May, when the Tigris would still be swollen by the melting of the snows in the Armenian hills. The stream would then be sufficiently rapid to carry to Baghdad a heavily laden raft, without the fear of obstruction from shallows and sand banks. This year, however, there was no marsh round the ruins, nor had any snow fallen in the mountains to promise a considerable rise in the river. I determined, therefore, to send the sculptures to Busrah in the month of March or April, foreseeing that as soon as the Bedouins had moved northwards from Babylonia, and had commenced their plundering expeditions in the vicinity of Mosul, I should be compelled to leave Nimroud. The Trustees of the British Museum had not contemplated the removal of either a winged bull or lion, and I had at first believed that, with the means at my disposal, it would have been useless to attempt it. They wisely determined that these sculptures should not be sawn into pieces, to be put together again in Europe, as the pair of bulls from Khorsabad. They were to remain, where discovered, until some favourable opportunity of moving them entire might occur; and I was directed to heap earth over them, after the excavations had been brought to an end. Being loath, however, to leave all these fine specimens of Assyrian sculpture behind me, I resolved upon attempting the removal, and embarcation of two of the smallest, and best preserved. Those fixed upon were the lion No. 2. from entrance b, hall Y, in plan 3., and a bull from entrance e, of the same hall. Thirteen pairs of these gigantic sculptures, and several fragments of others, had been discovered; but many of them were too much injured to be worth moving. I had wished to secure the pair of lions forming the great entrance into the principal chamber of the north-west palace2; the finest specimens of Assyrian sculpture discovered in the ruins. But after some deliberation I determined to leave them for the present; as, from their size, the expense attending their conveyance to the river would have been very considerable. I formed various plans for lowering the smaller lion and bull, for dragging them to the river, and for placing them upon rafts. Each step had its difficulties, and a variety of original suggestions and ideas were supplied by my workmen, and by the good people of Mosul. At last I resolved upon constructing a cart, sufficiently strong to bear any of the masses to be moved. As no wood but poplar could be procured in the town, a carpenter was sent to the mountains with directions to fell the largest mulberry tree, or any tree of equally compact grain, he could find; and to bring beams of it, and thick slices from the trunk, to Mosul. By the month of March this wood was ready. I purchased from the dragoman of the French Consulate a pair of strong iron axles, formerly used by M. Botta in bringing sculptures from Khorsabad. Each wheel was formed of three solid pieces, nearly a foot thick, from the trunk of a mulberry tree, bound together by iron hoops. Across the axles were laid three beams, and above them several cross-beams, all of the same wood. A pole was fixed to one axle, to which were also attached iron rings for ropes, to enable men, as well as buffaloes, to draw the cart. The wheels were provided with moveable hooks for the same purpose. Simple as this cart was, it became an object of wonder in the town. Crowds came to look at it, as it stood in the yard of the vice-consul's khan; and the Pasha's topjis, or artillery-men, who, from their acquaintance with the mysteries of gun carriages, were looked up to as authorities on such matters, daily declaimed on the properties and use of this vehicle, and of carts in general, to a large circle of curious and attentive listeners. As long as the cart was in Mosul, it was examined by every stranger who visited the town. But when the news spread that it was about to leave the gates, and to be drawn over the bridge, the business of the place was completely suspended. The secretaries and scribes from the palace left their divans; the guards their posts; the bazaars were deserted; and half the population assembled on the banks of the river to witness the manœuvres of the cart. A pair of buffaloes, with the assistance of a crowd of Chaldĉans and shouting Arabs, forced the ponderous wheels over the rotten bridge of boats.3 The multitude seemed to be fully satisfied with the spectacle. The cart was the topic of general conversation in Mosul until the arrival, from Europe, of some children's toys, — barking dogs, and moving puppets — which gave rise to fresh excitement, and filled even the gravest of the clergy with wonder at the learning and wisdom of the Infidels. To lessen the weight of the lion and bull, without in any way interfering with the sculpture, I reduced the thickness of the slabs, by cutting away as much as possible from the back. Their bulk was thus considerably diminished; and as the back of the slab was never meant to be seen, being placed against the wall of sun-dried bricks, no part of the sculpture was sacrificed. As in order to move these figures at all, I had to choose between this plan and that of sawing them into several pieces, I did not hesitate to adopt it. To enable me to move the bull from the ruins, and to place it on the cart in the plain below, it was necessary to cut a trench nearly two hundred feet long, about fifteen feet wide, and, in some places, twenty feet deep. A road was thus constructed from the entrance, in which stood the bull, to the edge of the mound. There being no means at my disposal to raise the sculpture out of the trenches, like the smaller bas-reliefs, this road was necessary. It was a tedious undertaking, as a very large accumulation of earth had to be removed. About fifty Arabs and Nestorians were employed in the work. On opening this trench it was found, that a chamber had once existed to the west of hall Y. The sculptured slabs, forming its sides, had been destroyed or carried away. Part of the walls of unbaked bricks, however, could still be traced. The only bas-relief discovered was lying flat on the pavement, where it had evidently been left when the adjoining slabs were removed. It has been sent to England, and represents a lion hunt. Only one lion, wounded, and under the horse's feet, is visible. A warrior, in a chariot, is discharging his arrows at some object before him. It is evident that the subject must have been continued on an adjoining slab, on which was probably represented the king joining in the chase. This small bas-relief is remarkable for its finish, the elegance of the ornaments, and the great spirit of the design. In these respects it resembles the battle-scene in the southwest palace4; and I am inclined to believe that they both belonged to this ruined chamber; in which, perhaps, the sculptures were more elaborate and more highly finished than in any other part of the building. The work of different artists may be plainly traced in the Assyrian edifices. Frequently where the outline is spirited and correct, and the ornaments designed with considerable taste, the execution is defective or coarse; evidently showing, that whilst the subject was drawn by a master, the carving of the stone had been entrusted to an inferior workman. In many sculptures some parts are more highly finished than others, as if they had been retouched by an experienced sculptor. The figures of the enemy are generally rudely drawn and left unfinished, to show probably, that being those of the conquered or captive race, they were unworthy the care of the artist. It is rare to find an entire bas-relief equally well executed in all its parts. The most perfect hitherto discovered in Assyria are, the lion hunt now in the British Museum, the lion hunt just described, and the large group of the king sitting on his throne, in the midst of his attendants and winged figures, which formed the end of chamber G, of the northwest palace, and will be brought to England. Whilst making this trench, I also discovered, about three feet beneath the pavement, a drain, which appeared to communicate with others previously opened in different parts of the building. It was probably the main sewer, through which all the minor watercourses were discharged. It was square, built of baked bricks, and covered in with large slabs and tiles. As the bull was to be lowered on its back, the unsculptured side of the slab having to be placed on rollers, I removed the walls behind it as far as the entrance a. An open space was thus formed, large enough to admit of the sculpture when prostrate, and leaving room for the workmen to pass on all sides of it. The principal difficulty was of course to lower the mass; when once on the ground, or on rollers, it could be dragged forwards by the united force of a number of men; but, during its descent, it could only be sustained by ropes. If not strong enough to bear the weight, they chanced to break, the sculpture would be precipitated to the ground, and would, probably, be broken in the fall. The few ropes I possessed had been expressly sent to me, across the desert, from Aleppo; but they were small. From Baghdad, I had obtained a thick hawser, made of the fibres of the palm. In addition I had been furnished with two pairs of blocks, and a pair of jackscrews belonging to the steamers of the Euphrates expedition. These were all the means at my command for moving the bull and lion. The sculptures were wrapped in mats and felts, to preserve them, as far as possible, from injury in case of a fall; and to prevent the ropes chipping or rubbing the alabaster. The bull was ready to be moved by the 18th of March. The earth had been taken from under it, and it was now only supported by beams resting against the opposite wall. Amongst the wood obtained from the mountains were several thick rollers. These were placed upon sleepers, or half beams, formed out of the trunks of poplar trees, well greased and laid on the ground parallel to the sculpture. The bull was to be lowered upon these rollers. A deep trench had been cut behind the second bull, completely across the wall, and, consequently, extending from chamber to chamber. A bundle of ropes coiled round this isolated mass of earth, served to hold two blocks, two others being attached to ropes wound round the bull to be moved. The ropes, by which the sculpture was to be lowered, were passed through these blocks; the ends, or falls of the tackle, as they are technically called, being led from the blocks above the second bull, and held by the Arabs. The cable having been first passed through the trench, and then round the sculpture, the ends were given to two bodies of men. Several of the strongest Chaldĉans placed thick beams against the back of the bull, and were directed to withdraw them gradually, supporting the weight of the slab, and checking it in its descent, in case the ropes should give way. My own people were reinforced by a large number of the Abou Salman. I had invited Sheikh Abd-urrahman to be present, and he came attended by a body of horsemen. The inhabitants of Naifa, and Nimroud having volunteered to assist on the occasion, were distributed amongst my Arabs. The workmen, except the Chaldĉans who supported the beams, were divided into four parties, two of which were stationed in front of the bull, and held the ropes passed through the blocks. The rest clung to the ends of the cable, and were directed to slack off gradually as the sculpture descended. The men being ready, and all my preparations complete, I stationed myself on the top of the high bank of earth over the second bull, and ordered the wedges to be struck out from under the sculpture to be moved. Still, however, it remained firmly in its place. A rope having been passed round it, six or seven men easily tilted it over. The thick, ill-made cable stretched with the strain, and almost buried itself in the earth round which it was coiled. The ropes held well. The mass descended gradually, the Chaldĉans propping it up firmly with the beams. It was a moment of great anxiety. The drums, and shrill pipes of the Kurdish musicians, increased the din and confusion caused by the war-cry of the Arabs, who were half frantic with excitement. They had thrown off nearly all their garments; their long hair floated in the wind; and they indulged in the wildest postures and gesticulations as they clung to the ropes. The women had congregated on the sides of the trenches, and by their incessant screams, and by the ear-piercing tahlehl, added to the enthusiasm of the men. The bull once in motion, it was no longer possible to obtain a hearing. The loudest cries I could produce were buried in the heap of discordant sounds. Neither the hippopotamus hide whips of the Cawasses, nor the bricks and clods of earth with which I endeavoured to draw attention from some of the most noisy of the group, were of any avail. Away went the bull, steady enough as long as supported by the props behind; but as it came nearer to the rollers, the beams could no longer be used. The cable and ropes stretched more and more. Dry from the climate, as they felt the strain, they creaked and threw out dust. Water was thrown over them, but in vain, for they all broke together when the sculpture was within four or five feet of the rollers. The bull was precipitated to the ground. Those who held the ropes, thus suddenly released, followed its example, and were rolling one over the other, in the dust. A sudden silence succeeded to the clamour. I rushed into the trenches, prepared to find the bull in many pieces. It would be difficult to describe my satisfaction, when I saw it lying precisely where I had wished to place it, and uninjured! The Arabs no sooner got on their legs again, than seeing the result of the accident, they darted out of the trenches, and seizing by the hands the women who were looking on, formed a large circle, and yelling their war-cry with redoubled energy, commenced a most mad dance. The musicians exerted themselves to the utmost; but their music was drowned by the cries of the dancers. Even Abd-ur-rahman shared in the excitement, and throwing his cloak to one of his attendants, insisted upon leading off the debkhé. It would have been useless to endeavour to put any check upon these proceedings. I preferred allowing the men to wear themselves out, — a result which, considering the amount of exertion, and energy, displayed both by limbs and throat, was not long in taking place. I now prepared, with the aid of Behnan, the Bairakdar, and the Tiyari. to move the bull into the long trench which led to the edge of the mound. The rollers were in good order; arid as soon as the excitement of the Arabs had sufficiently abated to enable them to resume work, the sculpture was dragged out of its place by ropes. Sleepers were laid to the end of the trench, and fresh rollers were placed under the bull as it was pulled forwards by cables, to which were fixed the tackles held by logs buried in the earth, on the edge of the mound. The sun was going down as these preparations were completed. I deferred any further labour to the morrow. The Arabs dressed themselves; and placing the musicians at their head, marched towards the village, singing their war songs, and occasionally raising a wild yell, throwing their lances into the air, and flourishing their swords and shields over their heads. I rode back with Abd-ur-rahman. Schloss and his horsemen galloped round us, playing the jerrid, and bringing the ends of their lances into a proximity with my head and body, which was far from comfortable; for it was evident enough that had the mares refused to fall almost instantaneously back on their haunches, or had they stumbled, I should have been transfixed on the spot. As the exhibition, however, was meant as a compliment, and enabled the young warriors to exhibit their prowess, and the admirable training of their horses, I declared myself highly delighted, and bestowed equal commendations on all parties. The Arab Sheikh, his enthusiasm once cooled down, gave way to moral reflections. " Wonderful! Wonderful! There is surely no God but God, and Mohammed is his Prophet," exclaimed he, after a long pause. " In the name of the most High, tell me, 0 Bey, what you are going to do with those stones. So many thousands of purses spent upon such things! Can it be, as you say, that your people learn wisdom from them; or is it, as his reverence the Cadi declares, that they are to go to the palace of your Queen, who, with the rest of the unbelievers, worships these idols? As for wisdom, these figures will not teach you to make any better knives, or scissors, or chintzes; and it is in the making of those things that the English show their wisdom. But God is great! God is great! Here are stones which have been buried ever since the time of the holy Noah, — peace be with him! Perhaps they were under ground before the deluge. I have lived on these lands for years. My father, and the father of my father, pitched their tents here before me; but they never heard of these figures. For twelve hundred years have the true believers (and, praise be to God! all true wisdom is with them alone) been settled in this country, and none of them ever heard of a palace under-ground. Neither did they who went before them. But lo! here comes a Frank from many days' journey off, and he walks up to the very place, and he takes a stick (illustrating the description at the same time with the point of his spear), and makes a line here, and makes a line there. Here, says he, is the palace; there, says he, is the gate; and he shows us what has been all our lives beneath our feet, without our having known anything about it. Wonderful! Wonderful! Is it by books, is it by magic, is it by your prophets, that you have learnt these things? Speak, 0 Bey; tell me the secret of wisdom." The wonder of Abd-ur-rahman was certainly not without cause, and his reflections were natural enough. Whilst riding by his side I had been indulging in a reverie, not unlike his own, which he suddenly interrupted by these exclamations. Such thoughts crowded upon me day by day, as I looked upon every newly discovered sculpture. A stranger laying open monuments buried for more than twenty centuries, and thus proving, — to those who dwelt around them, — that much of the civilization and knowledge of which we now boast, existed amongst their forefathers when our " ancestors were yet unborn," was, in a manner, an acknowledgment of the debt which the West owes to the East. It is, indeed, no small matter of wonder, that far distant, and comparatively new, nations should have preserved the only records of a people once ruling over nearly half the globe; and should now be able to teach the descendants of that people, or those who have taken their place, where their cities and monuments once stood. There was more than enough to excite the astonishment of Abd-ur-rahman, and I seized this opportunity to give him a short lecture upon the advantages of civilization, and of knowledge. I will not pledge myself, however, that my endeavours were attended with as much success as those of some may be, who boast of their missions to the East. All I could accomplish was, to give the Arab Sheikh an exalted idea of the wisdom and power of the Franks; which was so far useful to me, that through his means the impression was spread about the country, and was not one of the least effective guarantees for the safety of my property and person. This night was, of course, looked upon as one of rejoicing. Abd-ur-rahman and his brother dined with me; although, had it not been for the honour and distinction conferred by the privilege of using knives and forks, they would rather have exercised their fingers with the crowds gathered round the wooden platters in the court-yard. Sheep were of course killed, and boiled or roasted whole; — they formed the essence of all entertainments and public festivities. They had scarcely been devoured before dancing was commenced. There were fortunately relays of musicians; for no human lungs could have furnished the requisite amount of breath. When some were nearly falling from exhaustion, the ranks were recruited by others. And so the Arabs went on until dawn. It was useless to preach moderation, or to entreat for quiet. Advice and remonstrances were received with deafening shouts of the war-cry, and outrageous antics as proofs of gratitude for the entertainment, and of ability to resist fatigue. After passing the night in this fashion, these extraordinary beings, still singing and capering, started for the mound. Everything had been prepared on the previous day for moving the bull, and the men had now only to haul on the ropes. As the sculpture advanced, the rollers left behind were removed to the front, and thus in a short time it reached the end of the trench. There was little difficulty in dragging it down the precipitous side of the mound. When it arrived within three or four feet of the bottom, sufficient earth was removed from beneath it to admit the cart, upon which the bull itself was then lowered by still further digging away the soil. It was soon ready to be dragged to the river. Buffaloes were first harnessed to the yoke; but, although the men pulled with ropes fastened to the rings attached to the wheels, and to other parts of the cart, the animals, feeling the weight behind them, refused to move. We were compelled, therefore, to take them out; and the Tiyari, in parties of eight, lifted by turns the pole, whilst the Arabs, assisted by the people of Naifa and Nimroud, dragged the cart. The procession was thus formed. I rode first, with the Bairakdar, to point out the road. Then came the musicians, with their drums and fifes, drumming and fifing with might and main. The cart followed, dragged by about three hundred men, all screeching at the top of their voices, and urged on by the Cawasses and superintendents. The procession was closed by the women, who kept up the enthusiasm of the Arabs by their shrill cries. Abd-ur-rahman's horsemen performed divers feats round the group, dashing backwards and forwards, and charging with their spears. We advanced well enough, although the ground was very heavy, until we reached the ruins of the former village of Nimroud.5 It is the custom, in this part of Turkey, for the villagers to dig deep pits to store their corn, barley, and straw for the autumn and winter. These pits generally surround the villages. Being only covered by a light framework of boughs and stakes, plastered over with mud, they become, particularly when half empty, a snare and a trap to the horseman; who, unless guided by some one acquainted with the localities, is pretty certain to find the hind legs of his horse on a level with its ears, and himself suddenly sprawling in front. The corn-pits around Nimroud had long since been emptied of their supplies, and had been concealed by the light sand and dust, which, blown over the plain during summer, soon fill up every hole and crevice. Although I had carefully examined the ground before starting, one of these holes had escaped my notice, and into it two wheels of the cart completely sank. The Arabs pulled and yelled in vain. The ropes broke, but the wheels refused to move. We tried every means to release them, but unsuccessfully. After working until dusk, we were obliged to give up the attempt. I left a party of Arabs to guard the cart and its contents, suspecting that some adventurous Bedouins, attracted by the ropes, mats, and felts, with which the sculpture was enveloped, might turn their steps towards the spot during the night. My suspicions did not prove unfounded; for I had scarcely got into bed before the whole village was thrown into commotion by the reports of fire-arms, and the war-cry of the Jebour. Hastening to the scene of action, I found that a party of Arabs had fallen upon my workmen. They were beaten off, leaving behind them, however, their mark; for a ball, passing through the matting and felt, struck and indented the side of the bull. I was anxious to learn who the authors of this wanton attack were, and had organised a scheme for taking summary vengeance. But they were discovered too late; for, anticipating punishment, they had struck their tents, and had moved off into the desert. Next morning we succeeded in clearing away the earth, and in placing thick planks beneath the buried wheels. After a few efforts the cart moved forwards amidst the shouts of the Arabs; who, as was invariably their custom on such occasions, indulged, whilst pulling at the ropes, in the most outrageous antics. The procession was formed as on the previous day, and we dragged the bull triumphantly down to within a few hundred yards of the river. Here the wheels buried themselves in the sand, and it was night before we contrived, with the aid of planks and by increased exertions, to place the sculpture on the platform prepared to receive it, and from which it was to slide down on the raft. The tents of the Arabs, who encamped near the river, were pitched round the bull, until its companion, the lion, should be brought down; and the two embarked together for Baghdad. The night was passed in renewed rejoicings, to celebrate the successful termination of our labours. On the following morning I rode to Mosul, to enjoy a few days' rest after my exertions. The bull having thus been successfully transported to the banks of the river, preparations were made, on my return to Nimroud, for the removal of the second sculpture. I ordered the trench, already opened for the passage of the bull, to be continued beyond the entrance formed by the lions, or about eighty feet to the north. It was then necessary to move the slabs from behind these sculptures. The slabs in hall Y were plain, having only the usual inscription. The bas-reliefs on those adjoining the lion, in chamber G, had been almost entirely destroyed, apparently by the action of water. My preparations were completed by the middle of April. I determined to lower the lion at once on the cart, and not to drag it out of the mound over the rollers. This sculpture, during its descent, was supported in the same manner as the bull had been; but to avoid a second accident, I doubled the number of ropes and the coils of the cable. Enough earth was removed to bring the top of the cart to a level with the bottom of the lion. Whilst clearing away the wall of unbaked bricks, I discovered two small tablets, similar to those previously dug out in chamber B.6 On both sides they had the usual standard inscription, and they had evidently been placed where found, when the palace was built; probably as coins, and similar tablets, are now laid under the foundation-stones of edifices, to commemorate the period and object of their erection. As the lion was cracked in more than one place, considerable care was required in lowering and moving it. Both, however, were effected without accident. The Arabs assembled as they had done at the removal of the bull. Abd-ur-rahman and his horsemen rode over to the mound. We had the same shouting, and the same festivities. The lion descended into the place I had prepared for it on the cart, and was easily dragged out of the ruins. It was two days in reaching the river, as the wheels of the cart sank more than once into the loose soil, and were with difficulty extricated. The lion and bull were at length placed, side by side, on the banks of the Tigris, ready to proceed to Busrah, as soon as I could make the necessary arrangements for embarking them on rafts. The sculptures, which I had hitherto sent to Busrah, had been floated down the river on rafts, as far only as Baghdad. There they had been placed in boats built by the natives for the navigation of the lower part of the Tigris and Euphrates. These vessels, principally constructed of thin poplar planks, reeds, and bitumen, were much too small and weak to carry either the lion or the bull; and indeed, had they been large enough, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, in the absence of proper machinery, to move such heavy masses into them. I resolved, therefore, to attempt the navigation of the lower, as well as of the upper, part of the river with rafts; and to embark the lion and bull, at once, for Busrah. The raftmen of Mosul, who are accustomed to navigate the Tigris to Baghdad, but never venture further, pronounced the scheme to be impracticable, and refused to attempt it. Even my friends at Baghdad doubted of my success; principally, however, on the ground that the prejudices and customs of the natives were against me, — and every one knows how difficult it is to prevail upon Easterns to undertake anything, in opposition to their established habits. Such has been their nature for ages. As their fathers have done, so have they done after them, forgetting or omitting many things, but never adding or improving. As rafts meet with no insurmountable difficulties in descending, even from the mountainous districts of Diarbekir, to Baghdad, there was no good reason why they should not extend their journey as far as Busrah. The real obstructions would occur in the upper part of the river, which abounds in rapids, rocks, and shallows; and not in the lower, where there is depth of water, and nothing to impede the passage of large boats. The stream below Baghdad is sluggish, and the tide ascends nearly sixty miles above Busrah: these were the only objections, and they merely affected the time to be employed in the descent, and not its practicability. It was impossible by the most convincing arguments, even though supported by the exhibition of a heap of coins, to prevail upon the raftrnen of Mosul to construct such rafts as I required, or to undertake the voyage. I applied therefore to Mr. Hector, and through him found a man at Baghdad, who declared himself willing to make the great sacrifice generally believed to be involved in the attempt. He was indebted in a considerable sum of money, and being the owner of a large number of skins, now lying useless, he preferred a desperate undertaking to the prospect of a debtor's prison. It was not in any one's power to persuade him that his raft could reach its destination, or that even he could survive the enterprise; and it would have been equally impossible to convince him that my stake in the matter was greater than his own. As it was evident that no harm would come to him, but that, on the contrary, by entering into my service he would pay the greater part of his debts, and escape a prolonged residence in the gloomy subterranean abodes of hopeless debtors, I felt less compunctions of conscience in resorting to the last extremity. Indeed it was consoling to reflect that it was all for the man's own good. At any rate, I had to choose between leaving the sculptures on the river bank near Mosul, the sport of mischievous Arabs, and seeing them safely transported to Busrah, and ultimately to England. I did not, therefore, long hesitate upon the course to be pursued. Mullah Ali — for such was the name of my raft-contractor — at length made his appearance. He was followed by a dirty half-naked Arab, his assistant in the construction of rafts; and, like those who carried on his trade some two thousand years before, by a couple of donkeys laden with skins ready for use. Like a genuine native of Baghdad, he had exhausted his ingenuity in the choice of materials for the composition of his garments. There could not have been a more dexterous mixture of colours than that displayed by his antari, cloak, and voluminous turban. He began, of course, by a long speech, protesting, by the Prophet, that he would undertake for no one else in the world what he was going to do for me; that he was my slave and my sacrifice, and that the man who was not, was worse than an infidel. I cut him short in this complimentary discourse. He then, as is usual in such transactions, began to make excuses, to increase his demands, and to throw difficulties in the way. On these points I declined all discussion, directing Ibrahim Agha to give him an insight into my way of doing business, to recommend him to resign himself to his fate, as the contract had been signed, and to hint that he was now in the power of an authority from which there was no appeal. Mullah Ali made many vain efforts to amend his condition, and to induce, on my part, a fuller appreciation of his merits. He expected that these endeavours might, at least, lead to an additional amount of bakshish. At last he resigned himself to his fate, and slowly worked, with his assistant, at the binding together of beams, and logs of wood, with willow twigs to form a framework for a raft. There were still some difficulties, and obstacles to be surmounted. The man of Baghdad had his own opinions on the building of rafts in general, founded upon immemorial customs, and the traditions of the country. I had my theories, which could not be supported by equally substantial arguments. Consequently, he, who had all the proof on his side, may not have been wrong in declaring against any method, in favour of which, I could produce no better evidence than my own will. But, like many other injured men, he fell a victim to the " droit du plus fort," and had to sacrifice, at once, prejudice and habit. I did not doubt that the skins, once blown up, would support the sculptures without difficulty as far as Baghdad. The journey would take eight or ten days, under favourable circumstances. But here they would require to be opened and refilled, or the rafts would scarcely sustain so heavy a weight all the way to Busrah; the voyage from Baghdad to that port being considerably longer, in point of time, than that from Mosul to Baghdad. However carefully the skins are filled, the air gradually escapes. Rafts, bearing merchandise, are generally detained several times during their descent, to enable the raftmen to examine and refill the skins. If the sculptures rested upon only one framework, the beams being almost on a level with the water, the raftmen would be unable to get beneath them to reach the mouths of the skins, when they required replenishing, without moving the cargo. This would have been both inconvenient, and difficult to accomplish. I was therefore desirous of raising the lion and bull as much as possible above the water, so as to leave room for the men to creep under them. It may interest the reader to know how these rafts, which have probably formed for ages the only means of traffic on the upper parts of the rivers of Mesopotamia, are constructed. The skins of full-grown sheep and goats are used. They are taken off with as few incisions as possible, and then dried and prepared. The air is forced in by the lungs. The aperture is then tied up with string. A square framework, formed of poplar beams, branches of trees, and reeds, having been constructed of the size of the intended raft, the inflated skins are tied to it by osier and other twigs, the whole being firmly bound together. The raft is then moved to the water and launched. Care is taken to place the skins with their mouths upwards, that in case any should burst, or require filling, they can be easily opened by the raftmen. Upon the framework of wood are piled bales of goods, and property belonging to merchants and travellers. When any person of rank, or wealth, descends the river in this fashion, small huts are constructed on the raft by covering a common wooden takht, or bedstead of the country, with a hood formed of reeds and lined with felt. In these huts the travellers live and sleep during the journey. The poorer passengers bury themselves, to seek shade or warmth, amongst the bales of goods and other merchandise, and sit patiently, almost in one position, until they reach their destination. They carry with them a small earthen mangal or chafing-dish, containing a charcoal fire, which serves to light their pipes, and to cook their coffee and food. The only real danger to be apprehended on the river is from the Arabs; who, when the country is in a disturbed state, invariably attack and pillage the rafts. The raftmen guide their rude vessels by long oars, — straight poles, at the end of which a few split canes are fastened by a piece of twine. They skilfully avoid the rapids; and, seated on the bales of goods, work continually, even in the hottest sun. They will seldom travel after dark before reaching Tekrit, on account of the rocks and shoals, which abound in the upper part of the river; but when they have passed that place, they resign themselves, night and day, to the sluggish stream. During the floods in the spring, or after violent rains, small rafts may float from Mosul to Baghdad in about eighty-four hours; but the large rafts are generally six or seven clays in performing the voyage. In summer, and when the river is low, they are frequently nearly a month in reaching their destination. When the rafts have been unloaded, they are broken up, and the beams, wood, and twigs are sold at a considerable profit, forming one of the principal branches of trade between Mosul and Baghdad. The skins are washed and afterwards rubbed with a preparation of pounded pomegranate skins, to keep them from cracking and rotting. They are then brought back, either upon the shoulders of the raftmen or upon donkeys, to Mosul or Tekrit, where the men engaged in the navigation of the Tigris usually reside. On the 20th of April, there being fortunately a slight rise in the river, and the rafts being ready, I determined to attempt the embarkation of the lion and bull. The two sculptures had been so placed on beams that, by withdrawing wedges from under them, they would slide nearly into the centre of the raft. The high bank of the river had been cut away into a rapid slope to the water's edge. In the morning Mr. Hormuzd Rassam informed me that signs of discontent had shown themselves amongst the workmen, and that there was a general strike for higher wages. They had chosen the time fixed upon for embarking the sculptures, under the impression that I should be compelled, from the difficulty of obtaining any other assistance, to accede to their terms. Several circumstances had contributed to this manoeuvre. As I have already mentioned, the want of rain had led to a complete failure of the crops; the country around Nimroud was one yellow barren waste; the villagers had been exposed to several years of tyranny and oppression; during which their small stock of grain, unrenewed by fresh harvests, had gradually diminished. Last autumn, encouraged by the liberal policy of the new Pasha, they had sown the small supply of corn that had been hoarded up, and now that the crops had failed, their last hopes had perished. If they remained in the country, they could only look forward to starvation. They were consequently leaving the plain and migrating to the Kurdish hills, or to the lands under Mardin watered by the Khabour; where, by dint of irrigation, they could hope to raise millet, and other grain, sufficient to meet their wants until the winter rains might promise better times. The country around Nimroud was deserted; not a human being was to be seen within some miles of the place. Abd-ur-rahman, whose crops had failed like the rest, and who could no longer find pasture for his flocks in the Jaif, had followed the example of the villagers, and was moving northwards. Two or three days before, his Arabs, driving before them their sheep and cattle, and their beasts of burden laden with all the property they possessed, had passed under the mound, on their way to the territories of Beder Khan Bey. The Sheikh himself had spent the night in my house, to take leave of me prior to his departure. I consequently remained alone with my workmen, and the few Arabs who were cultivating millet along the banks of the Tigris. Not only, in case of a further emigration of the Jebour, should I have been left without the means of carrying on the excavations, but I should even have run considerable risk from the parties of Bedouins, who were now taking advantage of the absence of the Abou Salman to cross the river in search of plunder — scouring the country by night and by day. The time chosen by the Jebour to demand higher wages, and to threaten to leave me, was not, therefore, ill-chosen. They were persuaded that I should be compelled to agree to their demands, or to leave the lion and bull where they were. It was not, however, my intention to do either. T found, on issuing from the house, that the Arabs had already commenced their preparations for departure. The greater part of the tents had been struck, the flocks were collected together, the donkeys were half loaded, and all, men and women, were actively and busily engaged, except half a dozen families who did not show any desire to leave me. A few of the Sheikhs were hanging about the door of my court-yard with gloomy expectant looks, anxious to learn my decision, and little doubting, that on seeing the signs of packing, I would at once yield. However reasonable their demands might have been, the unceremonious fashion in which they were urged was somewhat repugnant to my feelings. There are some bad characters in most societies, who, mischievous themselves, contrive to lead others into mischief; and I was aware that one or two of the chiefs, who did not work, but managed to raise money from those who did, were the originators of the scheme. I ordered my Cawass and the Bairakdar to seize them at once, and then took leave of those who were preparing to depart. Their plans were somewhat disconcerted, and they went on sullenly with their arrangements. When at length their preparations for the march were completed, they moved off at a very slow pace, looking back continually, not believing it possible that I would obstinately persist in my determination to refuse a compromise. As a last attempt a deputation of one or two Sheikhs came to express a disinterested anxiety for my safety, should the Jebour leave the country. I did my best to quiet their alarms by employing the Tiyari to put my premises into a state of defence, and to reopen all the loop-holes, Avhich Ibrahim Agha had industriously made in the walls surrounding my dwelling, when they had been first built. Defeated in all their endeavours to make me sensible of the danger of my position, they walked sulkily off to join their companions, who took care to encamp for the night within sight of the village. Many families, however, refusing to desert me, pitched their tents under the walls of my house. The wives, too, of those who were going, had been to me, sobbing and weeping, protesting that the men, although anxious to remain, were afraid to disobey their Sheikhs. The tents of the Abou Salman were still within reach, and I despatched a horseman, without delay, to Sheikh Abd-ur-rnhman with a note, acquainting him with what had occurred, and requesting him to send me some of his Arabs to assist in embarking the bull. There was a rival tribe of the Jebour encamping at some distance from Nimroud, and I also offered them work. In the evening, Abd-ur-rahman, followed by a party of horsemen, came to Nimroud. He undertook at once to furnish me with as many men as I might require to place the sculptures on the rafts, and sent orders to his people to delay their projected march. Next morning, when the Jebour perceived a large body of the Abou Salman advancing towards Nimroud, they repented themselves of their manoeuvre, and returned in a body to offer their services on any terms that I might think fit to propose. But I was well able to do without them, and wished to convince them, that the method they had chosen to put forward their demands was neither rational, nor likely to prove successful. I refused, therefore, to listen to any overtures, and commenced my preparations for embarking the lion and bull with the aid of the Chaldeans, the Abou Salman, and such of my Arab workmen as had remained with me. The beams of poplar wood, forming an inclined plane from beneath the sculptures to the rafts, were first well greased. A raft, supported by six hundred skins, having been brought to the river bank, opposite the bull, the wedges were removed from under the sculpture, which immediately slided down into its place. The only difficulty was to prevent its descending too rapidly, and bursting the skins by the sudden pressure. The Arabs checked it by ropes, and it was placed without any accident. The lion was then embarked in the same way, and with equal success, upon a second raft of the same size as the first; in a few hours the two sculptures were properly secured, and before night they were ready to float down the river to Busrah. Many slabs, including the large bas-reliefs of the king on his throne, between the eunuchs and winged figures, which formed the end of chamber G, the altar-piece in chamber B, and above thirty cases containing small objects discovered in the ruins, were placed on the rafts with the lion and bull. After the labours of the day were over, sheep were slaughtered for the entertainment of Abd-ur-rahman's Arabs, and for those who had helped in the embarkation of the sculptures. The Abou Salman returned to their tents after dark. Abd-ur-rahman took leave of me, and we did not meet again: the next day he continued his march towards the district of Jezirah. I heard of him on my journey to Constantinople; the Kurds by the road complaining, that his tribe were making up the number of their flocks, by appropriating the stray sheep of their neighbours. I had seen much of the Sheikh during my residence at Nimroud; and although, like all Arabs, he was not averse to ask for what he thought there might be a remote chance of getting by a little importunity, he was, on the whole, a very friendly and useful ally. On the morning of the 22d, all the sculptures having been embarked, I gave two sheep to the raftmen to be slain on the bank of the river, as a sacrifice to ensure the success of the undertaking. The carcases were distributed, as is proper on such occasions, amongst the poor. A third sheep was reserved for a propitiatory offering, to be immolated at the tomb of Sultan Abd-Allah. This saint still appears to interfere considerably with the navigation of the river, and closed the further ascent of the Tigris against the infidel crew of the Frank steamer, because they neglected to make the customary sacrifice. All ceremonies having been duly performed, Mullah Ali kissed my hand, placed himself on one of the rafts, and slowly floated, with the cargo under his charge, down the stream.7 I watched the rafts, until they disappeared behind a projecting bank forming a distant reach of the river. I could not forbear musing upon the strange destiny of their burdens; which, after adorning the palaces of the Assyrian kings, the objects of the wonder, and may be the worship, of thousands, had been buried unknown for centuries beneath a soil trodden by Persians under Cyrus, by Greeks under Alexander, and by Arabs under the first descendants of their prophet. They were now to visit India, to cross the most distant seas of the southern hemisphere, and to be finally placed in a British Museum. Who can venture to foretell how their strange career will end? I had scarcely returned to the village, when a party of the refractory Jebour presented themselves. They were now lavish in professions of regret for what had occurred, and in promises for the future, in case they were again employed. They laid the blame of their misconduct upon their Sheikhs, and offered to return at once to their work, for any amount of wages I might think proper to give them. The excavations at Nimroud were almost brought to a close, and I had no longer any need of a large body of workmen. Choosing, therefore, the most active and well-disposed amongst those who had been in my service, I ordered a little summary punishment to be inflicted upon the captive Sheikhs, who had been the cause of the mischief, and then sent them away with the rest of the tribe. After the departure of the Abou Salman, the plain of Nimroud was a complete desert. The visits of armed parties of Arabs became daily more frequent, and we often watched them from the mound, as they rode towards the hills in search of pillage, or returned from their expeditions driving the plundered flocks and cattle before them. We were still too strong to fear the Bedouins; but I was compelled to put my house into a complete state of defence, and to keep patrols round my premises during the night to avoid surprise. The Jebour were exposed to constant losses, in the way of donkeys or tent furniture, as the country was infested by petty thieves, who issued from their hiding-places, and wandered to and fro, like jackals, after dark. Nothing was too small or worthless to escape their notice. I was roused almost nightly by shoutings and the discharge of fire-arms, when the whole encampment was thrown into commotion at the disappearance of a copper pot or an old grain sack. I was fortunate enough to escape their depredations. The fears of my Jebour increased with the number of the plundering parties, and at last, Avhen a small Arab settlement, within sight of Nimroud, was attacked by a band of Aneyza horsemen, who murdered several of the inhabitants, and carried away all the sheep and cattle, the workmen protested in a body against any further residence in so dangerous a vicinity. I found that it would not be much longer possible to keep them together, and I determined, therefore, to bring the excavations to an end. After the departure of the lion and bull, I opened, in the high conical mound or pyramid, a very deep trench, or rather well, which reached nearly to the natural platform of river deposits, forming the basis of the artificial structure. The whole mass was built of sun-dried bricks. There were no remains of stone or alabaster, nor indeed even of baked bricks, except in the thin outer coating of earth and rubbish which had accumulated over the unbaked bricks. As to the use to which this pyramid was applied, I can only conjecture that, being originally cased with stone or coloured baked bricks, it may have been raised over the tomb of some monarch; or may have served as an ornament, marking the site of the city from afar; or that it was intended as a watch-tower. It was opened on two sides, the trenches being carried completely into the centre; but no entrance, nor any traces of an interior chamber were found. It is possible, however, that on a more complete and extended examination than I was able to attempt, some discovery of great interest might be made, and that this may prove to be the very pyramid, raised above the remains of the founder of the city, by the Assyrian Queen — the " busta Nini " under which may still be some traces of the sepulchre of the great king. Although the sides of this high conical mound have been worn away and rounded, it is evident that its original shape was pyramidical. As soon as the outer covering, whether of stone or of baked bricks, had fallen off, or had been removed, the structure of unbaked bricks would rapidly decay, and would naturally assume its present form. That it was not at any period hollow, there can be no doubt. To examine it completely, in order to ascertain whether any remains exist beneath it, would be a labour requiring considerable time and expense. On the edge of the ravine, to the north of chamber B8, I discovered two enormous winged bulls, about seventeen feet in height, which had fallen from their places. They did not form an entrance, but each one stood alone, adjoining the great slabs with the colossal winged figures in chambers D, and E. I was unable to raise them, and the sculptured face of the slab was downwards. They had evidently been long exposed to the atmosphere, and the heads had been greatly injured. I now commenced burying in those parts of the ruins which still remained exposed, according to the instructions I had received from the Trustees of the British Museum. Had the numerous sculptures been left, without any precaution being taken to preserve them, they would have suffered, not only from the effects of the atmosphere, but from the spears and clubs of the Arabs, who are always ready to knock out the eyes, and to otherwise disfigure, the idols of the unbelievers. The rubbish and earth removed on opening the building, was accordingly brought back in baskets, thrown into the chambers, and heaped over the slabs until the whole was again covered over. But before leaving Nimroud and reburying its palaces, I would wish to lead the reader once more through the ruins of the principal edifice, and to convey as distinct an idea as I am able of the excavated halls, and chambers, as they appeared when fully explored. Let us imagine ourselves issuing from my tent near the village in the plain. On approaching the mound, not a trace of building can be perceived, except a small mud hut covered with reeds, erected for the accommodation of my Chaldĉan workmen. We ascend this artificial hill, but still see no ruins, not a stone protruding from the soil. There is only a broad level platform before us, perhaps covered with a luxuriant crop of barley, or may be yellow and parched, without a blade of vegetation, except here and there a scanty tuft of camel-thorn. Low black heaps, surrounded by brushwood and dried grass, a thin column of smoke issuing from the midst of them, may be seen here and there. These are the tents of the Arabs; and a few miserable old women are groping about them, picking up camel's-dung or dry twigs. One or two girls, with firm step and erect carriage, are perceived just reaching the top of the mound, with the water-jar on their shoulders, or a bundle of brushwood on their heads. On all sides of us, apparently issuing from under-ground, are long lines of wild -looking beings, with dishevelled hair, their limbs only half concealed by a short loose shirt, some jumping and capering, and all hurrying to and fro shouting like madmen. Each one carries a basket, and as he reaches the edge of the mound, or some convenient spot near, empties its contents, raising at the same time a cloud of dust. He then returns at the top of his speed, dancing and yelling as before, and flourishing his basket over his head; again he suddenly disappears in the bowels of the earth, from whence he emerged. These are the workmen employed in removing the rubbish from the ruins. We will descend into the principal trench, by a flight of steps rudely cut into the earth, near the western face of the mound. As we approach it, we find a party of Arabs bending on their knees, and intently gazing at something beneath them. Each holds his long spear, tufted with ostrich feathers, in one hand; and in the other the halter of his mare, which stands patiently behind him. The party consists of a Bedouin Sheikh from the desert, and his followers; who, having heard strange reports of the wonders of Nimroud, have made several days' journey to remove their doubts, and satisfy their curiosity. He rises as he hears us approach, and if we wish to escape the embrace of a very dirty stranger, we had better at once hurry into the trenches. We descend about twenty feet, and suddenly find ourselves between a pair of colossal lions, winged and human-headed, forming a portal. I have already described my feelings when gazing for the first time on these majestic figures. Those of the reader would probably be the same, particularly if caused by the reflection, that before those wonderful forms Ezekiel, Jonah, and others of the prophets stood, and Sennacherib bowed; that even the patriarch Abraham himself may possibly have looked upon them. In the subterraneous labyrinth which we have reached, all is bustle and confusion. Arabs are running about in different directions; some bearing baskets filled with earth, others carrying the water jars to their companions. The ChaldaBans or Tiyari, in their striped dresses and curious conical caps, are digging with picks into the tenacious earth, raising a dense cloud of fine dust at every stroke. The wild strains of Kurdish music may be heard occasionally issuing from some distant part of the ruins, and if they are caught by the parties at work, the Arabs join their voices in chorus, raise the war-cry, and labour with renewed energy. Leaving behind us a small chamber, in which the sculptures are distinguished by a want of finish in the execution, and considerable rudeness in the design of the ornaments, we issue from between the winged lions, and enter the remains of the principal hall. On both sides of us are sculptured gigantic, winged figures; some with the heads of eagles, others entirely human, and carrying mysterious symbols in their hands. To the left is another portal, also formed by winged lions. One of them has, however, fallen across the entrance, and there is just room to creep beneath it. Beyond this- portal is a winged figure, and two slabs with bas-reliefs; but they have been so much injured that we can scarcely trace the subject upon them. Further on there are no traces of wall, although a deep trench has been opened. The opposite side of the hall has also disappeared, and we only see a high wall of earth. On examining it attentively, we can detect the marks of masonry; and we soon find that it is a solid structure built of bricks of unbaked clay, now of the same colour as the surrounding soil, and scarcely to be distinguished from it. The slabs of alabaster, fallen from their original position, have, however, been raised; and we tread in the midst of a maze of small bas-reliefs, representing chariots, horsemen, battles, and sieges. Perhaps the workmen are about to raise a slab for the first time; and we watch, with eager curiosity, what new event of Assyrian history, or what unknown custom or religious ceremony, may be illustrated by the sculpture beneath. Having walked about one hundred feet amongst these scattered monuments of ancient history and art, we reach another door- way, formed by gigantic winged bulls in yellow limestone. One is still entire; but its companion has fallen, and is broken into several pieces — the great human head is at our feet. We pass on without turning into the part of the building to which this portal leads. Beyond it we see another winged figure, holding a graceful flower in its hand, and apparently presenting it as an offering to the winged bull. Adjoining this sculpture we find eight fine bas-reliefs. There is the king, hunting, and triumphing over, the lion and wild bull; and the siege of the castle, with the battering ram. We have now reached the end of the hall, and find before us an elaborate and beautiful sculpture, representing two kings, standing beneath the emblem of the supreme deity, and attended by winged figures. Between them is the sacred tree. In front of this bas-relief is the great stone platform, upon which, in days of old, may have been placed the throne of the Assyrian monarch, when he received his captive enemies, or his courtiers. To the left of us is a fourth outlet from the hall, formed by another pair of lions. We issue from between them, and find ourselves on the edge of a deep ravine, to the north of which rises, high above us, the lofty pyramid. Figures of captives bearing objects of tribute, — ear-rings, bracelets, and monkeys, — may be seen on walls near this ravine; and two enormous bulls, and two winged figures above fourteen feet high, are lying on its very edge. As the ravine bounds the ruins on this side, we must return to the yellow bulls. Passing through the entrance formed by them, we enter a large chamber surrounded by eagle-headed figures: at one end of it is a doorway guarded by two priests or divinities, and in the centre another portal with winged bulls. Whichever way we turn, we find ourselves in the midst of a nest of rooms; and without an acquaintance with the intricacies of the place, we should soon lose ourselves in this labyrinth. The accumulated rubbish being generally left in the centre of the chambers, the whole excavation consists of a number of narrow passages, panelled on one side with slabs of alabaster; and shut in on the other by a high wall of earth, half buried, in which may here and there be seen a broken vase, or a brick painted with brilliant colours. We may wander through these galleries for an hour or two, examining the marvellous sculptures, or the numerous inscriptions that surround us. Here we meet long rows of kings, attended by their eunuchs and priests, — there lines of winged figures, carrying fir-cones and religious emblems, and seemingly in adoration before the mystic tree. Other entrances, formed by winged lions and bulls, lead us into new chambers. In every one of them are fresh objects of curiosity and surprise. At length, wearied, we issue from the buried edifice by a trench on the opposite side to that by which we entered, and find ourselves again upon the naked platform. We look around in vain for any traces of the wonderful remains we have just seen, and are half inclined to believe that we have dreamed a dream, or have been listening to some tale of Eastern romance. Some, who may hereafter tread on the spot when the grass again grows over the ruins of the Assyrian palaces, may indeed suspect that I have been relating a vision.

|

|

|

|

|

1) The description of Herodotus agrees exactly with the present state of the country, and with the remains of canals still existing near the two rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates. "The Assyrians," he says, " have but little rain; the lands, however, are fertilised, and the fruits of the earth nourished, by means of the river. This does not, like the Egyptian Nile, enrich the country by overflowing its banks, but is dispersed by manual labour, or by hydraulic engines. The Babylonian district is intersected by a number of canals. Of all countries which have come under my observation this is the most fruitful in corn." (lib. i. c. 193.) 2) Entrance a, chamber B, plan 3. 3) The bridge of Mosul consists of a number of rude boats bound together by iron chains. Planks are laid from boat to boat, and the whole is covered with earth. During the time of the floods this frail bridge would be unable to resist the force of the stream; the chains holding it on one side of the river are then loosened, and it swings round. All communication between the two banks of the river is thus cut off, and a ferry is established until the waters subside, and the bridge can be replaced. 4) See Vol. I. p. 40. 5) The village was moved to its present site after the river had gradually receded to the westward. The inhabitants had been then left at a very inconvenient distance from water. 6) Vol.1, p. 116. 7) It is not improbable that the great obelisk which, according to Diodorus Siculus (lib. ii. c. 1.), was brought to Babylon from Armenia by Semiramis, was floated down on rafts supported by skins, in the same way that I transported the sculptures of Nineveh to Busrah. It was 130 feet in height, and 25 feet square at the base, and cut out of the solid rock, and must consequently, if the account be not a little exaggerated, have been of prodigious weight. The principal difficulty might probably appear to have been to place it on the raft; but this could have been accomplished by a simple method — by putting the beams forming the framework of wood, and fastening the skins under the obelisk, in some dry place, which would be overflowed during the periodical floods. When the water began to rise, by gradually removing the earth from beneath the skins, they could easily be filled with air; and when the stream had reached the raft they would lift up the obelisk, which could then be floated into the centre of the river. I should have adopted this method of moving the larger lions and bulls, had I been required to send them to Busrah without being provided with any mechanical contrivance, sufficiently powerful to embark such large weights by a simpler process. 8) Plan 3.

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD