By-Paths of Bible Knowledge

Book 10 - The Trees and Plants Mentioned in the Bible

Henry Chichester Hart, B.A. (T.C.D.), F.L.S.

Chapter 4

|

GRAIN AND VEGETABLES.

'THE original habitat of the farinaceous grasses,' says Humboldt, in his

Aspects

of Nature, 'like that of the domestic animals which have followed man since his

earliest migrations, is shrouded in obscurity. . . It is a most striking fact that

on one half of our planet there should be nations who are wholly unacquainted

with the use of milk and the meal yielded by narrow-eared grasses, whilst in the

other hemisphere nations may be found in almost every region who cultivate

cereals and rear mulch cattle. The culture of different cereals is common to

both hemispheres; but while in the New Continent we meet with only one species,

maize, we find in the Old World the fruits of Ceres (wheat, barley, spelt, and

oats) have been everywhere cultivated from the earliest ages recorded in

history.' Since Humboldt thus wrote, the labours of Alphonse De Candolle and

other botanists have thrown much light on the origin and history of these and

other food-plants, though the conclusions reached must necessarily be

conjectural in many cases. In the countries bordering the Mediterranean. wheat and barley have been known from the dawn of history; and millet also, though it held a subordinate place. Egypt was once the world's chief granary; afterwards Sicily and Barbary: but in modern times the vast empire of Russia, both north and south, and the rich plains of America, have become the most abundant sources of supply. Homer and the classic poets recognize three methods of utilizing the soil, viz. the rearing of cattle, the planting of fruit-trees, and the growing of corn. And in the sacred books of the Far East the question is asked: Who is the fourth that fills this earth with the greatest contentment?' and the answer given is, 'He who cultivates most corn, grass, and trees that afford nourishment.' So in the promise to the Israelites concerning their future inheritance, the fruit-trees, the pasturage, and the corn-lands are all included (Lev. xxv. 3, 4, 5, 7 Deut. viii. 8, 9, 13). What Herodotus said of Babylonia applied, though in a less degree, to ancient Egypt,—its native fruit-trees were few, but its soil produced the richest corn. Egypt, however, was a vast 'garden of herbs,' as well as a field of corn; and just as we are reminded of this fact in one of the earliest passages of patriarchal history, where Abram, driven from Southern Palestine by a temporary famine, goes down to sojourn in Egypt (Gen. xii. 10), so we have the first mention of esculent vegetables (the lentile excepted) when the Israelites, or rather the ' mixed multitude' of their camp-followers, bewailed the loss of ' the cucumbers and the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic,' which they had eaten beside the Nile. It is also observable that nearly all the vegetables and cereal grains mentioned in Scripture are known to have been cultivated in Egypt1. The Hebrew words denoting these edible plants are seldom of doubtful meaning, and the general terms for wild and cultivated grasses are fairly represented by their equivalents in the Authorized Version. There are, however, one or two exceptions. The word חָצֵר chatsir is rightly rendered 'grass' in most instances, but in two passages (Prov. xxvii. 25 and Isaiah xv. 6) it is unfortunately translated 'hay,' — an obvious error, as living and not cut grass is manifestly intended. 'Hay-making,' in our sense of the term, is not practised to any extent in Palestine; though the dried ' grass on the housetops' and fields is occasionally gathered. עֵשֶׂב eseb is generally rendered 'herb;' thus, in Psalm civ. 14, 'He causeth the grass (chatsir) to grow for the cattle, and herb (eseb) for the service of man.' Yet eseb is rightly translated grass in Psalm cvi. 20, 'an ox that eateth grass.' Another word, דֶּשֶׁא deshe, is rendered 'tender grass,' or more correctly, 'green herb.' There are numerous terms in the Old Testament denoting corn, some more comprehensive and others more specific. Of the former class, דָּנָן dagan, בֵּר bar, and שֵׁבֶר shebir are usually translated 'corn ' or occasionally 'wheat.' Dagan includes all kinds of grain produce, and is therefore frequently used in conjunction with 'wine' and ' oil.' It probably includes, in addition to wheat, barley, millet, and in some cases beans, peas, and lentiles. The 'corn' which Joseph's brethren went to seek in Egypt is denoted by the terms bar and shebir, and would seem to have been wheat only. The specific term for the latter, however, is חטָה chittah. There are also special words translated 'standing,' 'old,' 'parched,' 'beaten,' and 'ground' corn. The test word, shibboleth, applied to the Ephraimites by Jephthah's soldiers (Judg. xii. 6), and now incorporated into our modern English, signifies 'an ear of grain.' The above words, together with those translated 'straw,' 'stubble,' and 'chaff,' are fairly represented by correspondent terms in the English versions. In Isaiah v. 24 and xxxiii. II, however, 'chaff' should be read 'dry grass,' and in Jer. xxiii. 28, 'straw.' The first and third of these comparatively trivial errors are corrected in the Revised Version. It may be as well to remark that the absence of references to particular kinds of grain or vegetables in Scripture must not be regarded as adequate proof that such plants were wholly unknown to, or uncultivated by, the ancient inhabitants of Palestine. It is fair, however, to assume that any species which was both abundant and useful would almost certainly receive some notice, however incidental, in one or more of the sixty-six separate compositions which make up the Old and New Testaments. BARLEY (Heb. שְׂעׁרָה seorah, Gk. κριθῆ),

This familiar 'long-haired' grain—for such its Hebrew name implies, as contrasted with wheat—has a long and varied history, both sacred and classical; but we are chiefly concerned with its relation to Scripture lands and peoples. In the Old and New Testaments it is mentioned in nineteen books, often associated with wheat, which is named in some twenty-three or twenty-four. In the Old World the cultivation of cereals,—wheat, rye, barley, and oats, extends over an area of no less than forty degrees of latitude. The zone of barley and oats is the most northerly, reaching to 67° or even 70° N. lat., while that of wheat reaches only to about 57°, the zone of rye occupying the intermediate space. In Scandinavia and other parts of Northern Europe, barley-bread is still a predominant article of diet, either alone or mixed with oaten flour. This is also the case in some districts of the Highlands of Scotland and the north of Ireland. But, at the present time, barley is raised chiefly for the production of fermented liquors and not as a staple article of food. This fact is one which exemplifies in a striking manner the advance of the British people in material comforts. A hundred and twenty years back, wheaten bread was a rare luxury among the poorer classes; barley, oats, and rye supplying the place of the costlier grain. Now, Dr. Johnson's well-known sarcasm as to the relative consumption of ' oats' north and south of the Tweed, has lost its sting; and our Scottish fellow-countrymen eat oatmeal from habit and choice rather than from any lack of wheat, while rye and barley are falling altogether into disuse as breadstuffs. There are numerous varieties of the cultivated kinds of barley (Hordeum), but it is difficult to determine how many distinct species exist. In Palestine four or five species are reported, including the 'summer' and 'winter' barley of our English farmers. Oats (Avena saliva) and rye (Secale cereale) are not grown in that country, nor does either appear to be mentioned in the Bible (see RYE). But barley was so common that it supplied the Hebrews, like ourselves, with a unit of linear measurement. With us 'three barley-corns make one inch,' according to the school-books; and in Biblical metrology Captain Conder has discovered the same simple standard of length; two barley-corns making a 'finger-breadth,' sixteen a 'hand‑breadth,' twenty-four a 'span,' and forty-eight a 'cubit' of sixteen inches2. We first meet with distinct mention of barley as an Egyptian crop; when smitten by the hail which formed the seventh plague, the barley was already 'in the ear,' but the wheat had not yet 'grown up,' Exod: ix. 31, 32. The barley harvest, both in Egypt and in Palestine, as we further see from Ruth ii. 23, precedes that of wheat; and the two extend through several weeks. On the plain of Philistia—the granary of ancient Canaan, as the Shunammite well knew (2 Kings viii. 1, 2)—the whole harvesting lasts from April till June; and, indeed, the inequalities of climate in Palestine must needs affect to a considerable extent the time of reaping all kinds of crops. In Elisha's day, we read of a present of barley loaves, 'bread of the first fruits,' with 'fresh ears of corn in a sack' (2 Kings iv. 42, R. V.): this was probably parched corn from the 'fresh ears' of the yet green wheat, according to the directions for the meat offering in Lev. ii. 14. Such ears were sometimes crushed, and boiled with meat. In primitive times barley bread was a general article of diet; but as the nation prospered it became more especially the food of the poor (Judg. vii. 13; Ruth iii. 15; 2 Sam. xvii. 28). Such we learn was the case in Egypt also. Barley was then considered inferior to wheat, as it is at the present time. The Syrian farmers complain that their extortionate rulers have left them 'only barley bread to eat;' and the Bedouins scornfully term their enemies 'eaters of barley bread.' It was the few cakes of barley in the possession of a peasant lad, which at the word of the Redeemer furnished food to five thousand men. In the reign of Solomon barley was provided in allotted quantities for the royal stables (I Kings iv. 28), wheat not being given to horses or other domestic animals. The king also paid the Tyrian workmen partly in barley; and his successor, Jotham, received a similar tribute from the Ammonites, when that nation was subject to Israel (2 Chron. ii. 10; xxvii. 5). The Egyptians prepared a sort of beer, called zythus or zythum, from this grain; thus anticipating the common drink of Western nations. It is mentioned by several ancient authors, as Diodorus, Strabo, and Herodotus, and among later writers by Pliny and Dioscorides. But of this beverage there is no trace in the Old Testament, and we may infer that it was either not known to or not adopted by the inhabitants of Palestine. That the nutritive value of this grain was known to the ancients is evidenced by the fact that polenta or barley porridge was given to the public gladiators to strengthen them for their contests. Both ' barley water' and ' decoction of barley' are recognized in the modern pharmacopoeia. BEANS (Heb. פּוֹל poi). PULSE (Heb. זֵרׂעִים zeroim).

Like the cereal grasses, the cultivated vegetables are found from the dawn of history following the migrations of man. The value of the seeds of pod-plants, such as peas, beans, vetches, and lentiles, would soon be recognized in the countries where they originally grew wild; but what those countries were cannot now be fully deter-mined. Both pea and bean are of very high antiquity. Homer mentions both, describing the arrow shot by Helenus at Menelaus as rebounding from his armour, 'as dark beans and (chick?) peas leap from the winnower's fan3.' The Greeks appear to have brought the pea into Italy through Asia Minor, whence it is supposed to have come 'from the region of the Pontus and Caucasus,' this vegetable not having been known, it would seem, to the ancient inhabitants of either Palestine or Egypt. But BEANS (Vicia faba) were undoubtedly cultivated in both countries, and largely eaten by the peasantry, though the Egyptian priests were not allowed to partake of them—a prohibition extending to some other articles of vegetable diet. Considering that the Leguminosae, or pod-bearing order of plants, is represented in Palestine by more than 350 species, it is somewhat singular that the references in Scripture to the edible kinds—PULSES, as they are termed —are so extremely scanty. Probably they were much more largely cultivated than the silence of Biblical writers would lead us to suppose. Indeed, in the Mishna the bean is mentioned as among the first-fruits to be offered, and it is implied that this and other esculents were ground into meal. Pulses are casually alluded to in the history of Daniel and his fellow-captives at Babylon, who are said to have requested a diet of 'pulse' in lieu of the meat—to them unclean—provided for the king's table (Dan. i. 12-16). The word here used is zeroim, or 'seeds,' a general term, though probably including the leguminous vegetables, if not referring specially to them. Our translators (A.V. and R.V.) have also supplied the term 'pulse,' on reasonable grounds, in the account of the timely supplies of food brought by the loyal Gileadites, Machir, Shobi, and Barzillai, for David and his men, when in flight from Absalom at Mahanaim (2 Sam. xvii. 27-29). 'Parched' (corn) is mentioned, and the adjective repeated; it is therefore probable that, as at the present time, roasted corn and parched seeds of leguminous vegetables were formerly a common article of food. In the same passage 'beans' are specified for the first time in Scripture. The second and only other reference is in Ezekiel's prophecy (ch. iv. 9), where he is directed to make bread of several kinds of grain and of beans and lentiles. Both these references, incidental as they are, imply the common use of the bean. In modern Palestine beans are sown in November and ripen in the time of wheat harvest; while in Egypt they are still earlier in coming to perfection. Canon Tristram saw a field in full blossom during the last week of February, near Nablous. They are cut down with scythes, crushed with a rude machine, and so prepared for the food of camels, goats and oxen; or they are triturated, so as to remove the skins, and then sent to the markets. The ancient Egyptians delighted in a vegetable diet, which, indeed, constituted the chief means of sustenance of the poorer classes, and, except on public occasions, was conspicuous on the tables of the rich. In classic times beans and chick-peas were among the common food of the humbler grades of the Italian population; and the names of the proud families of Fabius, Piso, and Cicero were derived respectively from the bean (faba), pea (pisum), and chick-pea (cicer). Both the latter seeds are now raised in Syria. CUCUMBERS (Heb. קִשֻּׁאִם kishuim). GOURD (Heb. קִיקָיוֹן kikayon, פַּקֻּעׂת pakhuoth). MELONS (Heb. אֲבַטִחִים abattichim). WILD VINE (Heb. נֶּפֶן שֶׂדֶה gephen sadeh).

Most refreshing to the inhabitants of the warmer regions of the globe are the fruits yielded by the Gourd family of plants, called, from a familiar and representative genus, Cucurbitaceae; and this notwithstanding a bitter principle which some of them contain, and which needs artificial treatment for its removal. The order comprises the gourds, cucumbers.. and melons, the pumpkin and vegetable-marrow, with the Colocynth and Elaterium, well known as yielding powerful drugs. They vary greatly in flavour, partly according to climate and cultivation; and we may contrast the lusciousness of the water-melon and sugar-melon with the harshness of our cucumber, or the insipidity of the pumpkin. But in Southern Europe, and still more in Egypt, Syria, and the Farther East, their cooling pulp and juice are most refreshing and healthful. We need not altogether wonder that the Israelites, wearily marching through the arid solitudes of the Sinaitic peninsula, thought more of the cucumbers and water-melons of which they had had no lack in Egypt, rather than of the cruel bondage which was the price of those luxuries. In the above-quoted passage, more than one kind of CUCUMBER (Cucumis) may be included, or the reference may be to the Egyptian or Hairy Cucumber (C. chate), which Hasselquist called 'the queen of cucumbers, refreshing, sweet, solid, and whole-some.' The Egyptians, however, cultivated more than one kind, and three or four are now grown in Palestine, including the above, and the species familiar on Western tables (C. sativus). In Isaiah's allusion (ch. i. 8) to 'a lodge in a garden of cucumbers '—that is, a booth or shed of branches erected for the use of the watcher or keeper, as in vineyards—the word used is derived from the same root. Gesenius thinks that the name of the city called Dilean (דִּלְעָן), in Judah's territory (Josh. xv. 38), has the meaning of 'cucumber-town' or 'field.' Still more valued in modern, and probably in ancient times, are the water-melons, another species of Cucumis (C. melo), which grow exuberantly in some parts of the coast plain of Palestine. Miss Rogers, in Domestic Life in Palestine, says of one district near Caesarea:' Looking westward we could see a broad strip of the now sunlit Mediterranean, beyond the melon gardens, which are by no means picturesque. The large rough melon leaves lie flat on the level ground, which looks as if it were strewn with great green and yellow marbles, fit for giants to play with. There were no hedges or trees to break the monotony of the view. We wished to buy a few melons, but the overseer of the labourers told us that we might take as many as we liked, but he could not sell them except by hundreds. After a refreshing rest we re-mounted and rode through miles and miles of melon ground.' It was doubtless for these delicious products that the multitudes longed, the Hebrew and Arabic names being almost identical; and they doubtless formed a common article of food. The water-melon is supposed to have come originally from tropical Africa; thence to Egypt, and so into Asia, and at a later date to Southern Europe, where its different varieties are equally esteemed. It is extensively grown in Egypt during the rise of the Nile, and in the month of March on the sand-banks beside the river; and was doubtless so cultivated in Old Testament days. Hasselquist says that it attains a very large size, one fruit yielding several pounds' weight of juice. A medicinal oil is extracted from the seeds; indeed, the melon serves the poorer classes with meat, drink, and medicine. Professor Hehn connects the word cucumis with cumera or cumerum, a covered vessel, in allusion to the use of the rind of fruits of the gourd tribe from time immemorial. This leads to a consideration of the GOURD, which afforded to the discouraged prophet Jonah so welcome a shade, and so salutary a lesson. Much useless controversy has been expended, even from the days of Jerome and Augustine, on the identification of this plant; whose growth, if the plain narrative be accepted, was miraculously accelerated for the prophet's benefit. The extent and frequency with which gourds are trained over arbours and along the walls of houses in the East, their singularly rapid growth and agreeable shade, beside the fact of their actual cultivation in Assyria, would seem amply sufficient reasons for accepting the received translation. But on philological grounds a claim has been advanced in favour of the Palma Christi, or castor-berry, or wild sesamum, the Ricinus communis of botanists, a broad‑leaved shrub of the spurge tribe, from which the well‑known medicinal oil is obtained. The plant was cultivated by the ancient Egyptians for the sake of its oil, and is still grown to some small extent in that country. It is also found in Palestine and Assyria, and its oil extracted. But the Jewish opinion is in favour of identifying the Arabic name kurah with the kikayon of Jonah; and, according to Niebuhr, this was the view taken by the Jews and Christians residing at Mosul, one of the localities on the Tigris which, since Niebuhr's day, have been shown to occupy the site of ancient Nineveh. Dr. Thom-son's testimony—virtually that of a native of the Holy Land—seems decisive. 'Orientals,' he says, 'never dream of training a castor-oil plant over a booth, or planting it for a shade, and they would have but small respect for any one who did.' It may be added that the gourd tribe are as remarkable for their vegetative growth as for the rapidity with which it is attained. The bottle-gourds of the West Indies reach dimensions of six feet in length by two in thickness, and the rind of one has been stated to hold twenty-two gallons. Pliny speaks of pumpkin calabashes for containing wine. In the island of Cyprus Mrs. Scott-Stevenson describes the houses as 'shaded by gigantic gourds, with fan-like leaves, forming a natural porch at every doorway.' A different word is used in 2 Kings iv. 39, where we read that one of the young men in attendance on the prophet Elisha went out 'to gather herbs, and found a wild vine, and gathered thereof wild gourds his lap full, and came and shred them into the pot of pottage: for they knew them not . . . And it came to pass, as they were eating of the pottage, that they cried out and said, O thou man of God, there is death in the pot' This plant of course was no literal vine, since its fruit was of a kind to be shred or sliced into the soup or broth. The Rabbinical writers also state that the pakkuoth contained seeds which yielded an oil, which is the case with many of the Cucurbitaceae. The colocynth (Citrullus colocynthus) seems to be the plant intended. It is a well-known medicine, bitter and drastic; its flavour would at once excite alarm, and its properties would render it highly poisonous if eaten as food. 'The colocynth,' says Canon Tristram, 'grows most abundantly in the barren sands near Gilgal, and all around the Dead Sea in the low flats, covering the ground with its tendrils. We never saw a colocynth elsewhere.' Dr. Bonar also speaks of it as a plant of the Desert; but it is certainly found wild also on the maritime plains. It grows also, and is used medicinally, in the island of Cyprus. It is gathered in large quantities, and exported to Europe; and it is a familiar object in our chemists' shops. It was easy for an inhabitant of the highlands of Palestine, as Dr. Tristram points out, to mistake this unfamiliar vegetable for one of the harmless kinds; and as it was a time of scarcity, he would be glad to appropriate any likely esculent. The bright orange rind of the colocynth, when fully ripe, taken in connection with the bitter seeds and dust which it then contains, seems to point to it as identical with the 'apple of Sodom' mentioned by Josephus, and celebrated by the poet Moore in the oft-quoted lines, and by Byron in Childe Harold:

Other writers call them 'oranges,' and the tradition is undoubtedly a very ancient one. It has been suggested that the 'apples of Sodom' were galls of the Quercus infectoria; but oaks do not grow on the shores of the Dead Sea, and the 'fruit' in question is said to be a product of that district especially. The Solanum sanctum, a plant of the nightshade tribe, and a native of the same tropical region, has been put forward as fulfilling the requirements of the Jewish historian's description. It is a thorny shrub, and 'bears a large crop of [poisonous] fruit, larger than the potato-apple, perfectly round, yellow at first, and when quite ripe changing to a brilliant red.' The pulpy interior dries up, leaving only a quantity of black seeds. Canon Tristram regards this Solanum as more probably representing the 'thorns' of the 'hedge' in Proverbs xv. 19 and the ' brier' of Micah vii. 4. The 'vine of Sodom' and 'grapes of gall' seem to point in the same direction; a vine-like, spreading plant, with intensely bitter fruit, being apparently indicated. Some of the nightshades contain a bitter principle, but it is much less marked than in the colocynth. GARLICK (Heb. שׁוּמִים shumim). LEEKS (Heb. חָצִיר chalsir). ONIONS (Heb. בְּצָלִים belsalim).

The somewhat romantic history of these bulbous vegetables contrasts singularly with their homely associations, and not less with the cursory notice bestowed upon them in the sacred writings. The botanist includes them all in the genus Allium, of which between thirty and forty species are now found growing in Palestine. This fact strongly confirms the testimony of secular historians as to the culture of these pungent roots by the Hebrews of former times, as well as by their neighbours the Egyptians, from whom we may infer they derived their acquaintance with them. Either Syria or Egypt is thought to be the country in which they were first adopted by man after emigrating from their original home in the interior of Asia. Garlick and onions were provided for the table of the Persian kings; Homer (Il., lib. xi.) introduces Hecamede as offering a drink flavoured with onions to the veteran Nestor; and after that poet's age they became the common food of the people of both Greece and Italy. But with increased refinement of taste, the scent of garlick and onions became an object of aversion. The aristocrat could not endure contact with those who fed on so gross a diet, as is shown in the comedies of Aristophanes and Plautus; while the squeamish Horace (Epod. iii.) deems garlick only fit for condemned criminals4. But in Syria, as in modern Russia, no such objection to these odorous vegetables seems ever to have existed; indeed, in the East, perfumes are relished which we could scarcely tolerate. We, on our part, are more sensitive in such matters than our ancestors, of whom we may say, as Varro of the Romans, 'The words of our forefathers no doubt were odorous of garlic, but the breath of their spirit was all the nobler.' 'The Israelites,' as Professor Helm humorously observes,' ever since their regretful thoughts strayed away from the sandy waste around them to the garlick of Egypt, have remained fast friends of that vegetable, both before and since the destruction of Jerusalem, whether at home in their Holy Land, or in the Dispersion under Talmudic and Rabbinic rule.' The LEEK (Allium porrum) appears to have been the primitive object of cultivation. Its Hebrew name, meaning 'herb' or 'grass,' suggests that it was at first regarded by the Semites as 'the herb,' par excellence. It is remarkable that in the languages of the Celts, Germans, and Slavonic nations, leek (Anglo-Saxon leác) has the original meaning of 'succulent herb.' Thus GARLICK (A. sativum) is gârleác, the cloven leek,' while ONION (A. cepa) is the ' undivided ' leek,— unio, unus, one. According to Herodotus, the pyramid builders of Egypt were fed on radishes, onions, and garlick; which, together with lentiles, formed the chief vegetables of that prolific land. They appear among the offerings presented to the gods; and being in a sense sacred, were prohibited more or less absolutely to the priesthood. For this Juvenal ridicules the Egyptians as a people whose 'gods grew in their kitchen gardens.' Hasselquist praises in the highest terms the mild and agreeable flavour of the Nile onions. The leek is the national emblem of Wales, and among the Northern Teutons, as in Asia Minor and Greece, magic powers were attributed to it. It was also a symbol of victory. A writer in Science Gossip quotes a 'tradition ' prevailing 'in the East, that, when Satan stepped out of the garden of Eden, after the Fall of Man, onions sprang up from the spot where he planted his right foot, and garlick from that which his left foot touched.' This must be a relic of the magical properties attributed to these vegetables, and not a sarcasm on their powerful odour, to which Orientals would feel no objection. The classic name porrum has been derived from the Celtic term Pori, to eat, whence our porridge. The shallot, another Syrian species of Allium, carries its descent in its name. It is a corruption of eschallot (Fr.), the onion of Ascalon, described by the Greek botanist Theophrastus, whose modern representatives have re-named it A. Ascalonicum. It still grows, both wild and in gardens, around the site of the old Philistine city. Pliny says this species is good for sauces. We are supposed to owe its introduction to the Crusaders5. LENTILES (Heb. עֲדָשִׁים adashina).

The LENTILE (Ervum lens) is the smallest of the cultivated leguminous plants. It is a slight-growing annual, with compound leaves and tendrils; and bears purple flowers, which develop into pods, each containing two or three convex beans. It grows to a height of six or eight inches, and in the warm plains of Egypt ripens by the end of March. In Palestine, however, the harvest of this useful bean does not fall until June or July, when the plants are either reaped with a scythe or pulled by hand, and then carried to the threshing-floor. From one of these countries, and not from Central Asia, the lentile is supposed to have reached Europe. On the borders of Egypt stood Phakussa—the 'lentile town' — but the meanings of the Greek word φακός and the Latin name lens are quite unknown. The plant made its way into Central and Northern Europe, and is cultivated in many parts of the Continent, whence it is imported into our own island. Its nutritive qualities are well known, and have been taken advantage of in the manufacture of 'Ervalenta' and 'Revalenta' foods for invalids; but the flavour of the lentile is scarcely agreeable to English palates. It is not so, however, in the East even among European residents. Speaking of the pottage made of the red variety of lentile—considered superior to the brown—Dr. Thomson says he 'found it very savoury indeed;' and adds that 'Frank children,' born in Palestine, 'are extravagantly fond of this same adis pottage,' which, 'when cooking, diffuses far and wide an odour extremely grateful to a hungry man.' It was thus that the faint and famished Esau cried out, at the first sight of his brother's tempting meal, 'Feed me, I pray thee, with the red—this red,' into which he might dip the soft 'bread,' spoon-fashion, as now his descendants are accustomed to do. 'So Jacob gave Esau bread, and pottage of lentiles' (Gen. xxv. 29-34). Barzillai and his companions brought contributions of lentiles, with the 'parched corn' and 'beans' already noticed, for David and his soldiers, because they were ' hungry and weary;' and 'a piece of ground full of lentiles6' was the scene of a memorable exploit of Shammah the Hararite, one of the ' first three 'of David's warriors (2 Sam. xvii. 28; xxiii. II). Len-tiles were also among the ingredients of which the prophet Ezekiel was directed to make bread as a sign of the coming siege of Jerusalem (Ezek. iv. 9). It is stated that in Upper Egypt the bread eaten in some districts is made entirely of lentile flour, wheat being scarce. Among the ancient Egyptians this vegetable held a high place. It was among the chief articles of diet used by the peasantry and artisans, and some varieties (such as the Pelusium lentiles) were of more than local celebrity7. On a bas-relief at Thebes the making of soup or porridge is shown, one man being engaged, like Jacob, in 'seething' the 'pottage,' while his companion brings faggots for the fire, the beans being piled up in baskets hard by. With the other vegetables before named, lentiles were offered to the gods, with other first-fruits of the field produce; and having a sacred character, were forbidden to the priestly caste. MILLET (Heb. דֹּחַן dochan).

MILLET, one of the cultivated grasses—the Panicum miliaceum of botanists—became an article of human diet at a very remote period in both East and West. In this country it is scarcely recognized, except as food for poultry, for which purpose a limited quantity is imported from the Mediterranean, hardly any being grown here. But it is cultivated throughout Eastern lands as a minor corn-plant …and anciently immense quantities were raised in Babylonia and Assyria, in Western Asia, and in Central and Southern Europe; until wheat, rice, and maize superseded the inferior grain. In the memorable 'Retreat of the Ten Thousand' the Greeks marched 'through the country of the Millet-eaters;' and the Spartans were called by a similar name. The Celts, Gauls, and Scythians sowed millet; and although mentioned but once in Scripture, it was probably included among the bread-plants of the ancient Hebrews. Several species of the genus Panicum grow in Palestine; they are stout annual grasses, with broad leaves, and bear dense clusters of small seeds. The above must be distinguished from the black millet or dhourra of the Arabs, Sorghum vulgare, which seems to have been known to the Egyptians of former days, as it is to their modern descendants. It is now much cultivated throughout the Mediterranean region, but came originally from India. 'RIE' (R.V. SPELT), (Heb. כֻסֶּמֶת kussemeth). WHEAT (Heb. חִטָּה chittah, Gk. σῖτος).

The knowledge of this, to us, the most valuable and interesting of all the cereals, dates back to prehistoric times; though its name, signifying white (corn) is inferred to point to an acquaintance with an older and darker-coloured grain. The old Greek word is traced back to the same root as our English furse, Anglo-Saxon fyrs ---a name originally given to a grass, and subsequently transferred to this grass, by way of distinction. However this may be, we meet with mention of WHEAT in some of the earliest pages of sacred history, as a special object of culture in Palestine, Egypt, and the neighbouring countries. The eldest son of Jacob went out 'in the days of wheat harvest' (Gen. xxx. 14); but, years before, Isaac had 'sown' in the land of Gerar in the south-west, and 'reaped a hundred-fold;' and had included, in the blessing bestowed on the disguised Jacob, 'plenty of corn and wine' (ch. xxvi. 12; xxvii. 28). At a still earlier epoch, Egypt was renowned for her superabundant produce of grain—enough to support her own teeming population, and to meet the wants of other countries when their own supplies were inadequate (Gen. xii. to, &c.). Less extensive, but not less valuable, were the wheat fields which overspread the Syrian plains; from Philistia on the western seaboard to the far-stretching land beyond the eastern hills—the Belka of the modern Arabs; and from Coele-Syria, beyond Lebanon, to the 'South country,' whither the patriarchs more than once 'went down' from the hills of Judah. The wheat grown in Palestine now, and probably in Bible days, does not differ from the species with which we are acquainted—the Triticum vulgare of botanists; but there are sundry varieties. One of these was called Heshbon wheat' by Captain Mangles. It is a bearded kind, bearing several ears on one stalk, and is remark-ably prolific, one calculation giving double the number of grains in an ear as compared with English wheat, with nearly thrice the weight, and a taller stalk. Canon Tristram supposes that this was the 'wheat of Minnith,' exported by the Hebrews to Phoenicia, as stated by the prophet Ezekiel (xxvii. 17). Minnith was in the territories of the ancient Ammonites, and is now identified with Menjeh, a city around whose ruins lay 'one sea of wheat' when the last-named traveller visited it. The Egyptian wheat was also a bearded kind, and the variety called 'mummy wheat,' when sown, produced a stalk bearing several ears, like that of Heshbon, and such as the Pharaoh of old saw in his dream (Gen. xli. 22). It is also shown on the monuments, and is occasionally grown in Lower Egypt at the present day. Anciently, immense crops of wheat and barley were raised in the rich plains of the Assyrian and Babylonian empires. In the province of Susiana, according to Strabo, the yield of wheat was from one to two hundred-fold,—a degree of fertility remarkable even in the East (Gen. xxvi. 12). In Palestine, wheat is sown in November or December, and reaped in May or June, according to the precise climate and locality. In Egypt the harvest was about a month earlier, in both countries the barley preceding the wheat by three or four weeks. RYE is essentially a northern species (Triticum secede), and is now scarcely known in Palestine or Egypt. The Hebrew word rendered in the Authorized Version 'rie,' in Exod. ix. 32, Isaiah xxviii. 25, and (much less excusably) 'fitches' (i.e. vetches) in Ezek. iv. 9, is with more probability translated 'spelt' in all three passages of the Revised, and in the margin of the older Version. SPELT (Triticum spelta) is a hard and rough-grained wheat, bearded, but much resembling the ordinary kind. It seems to have been cultivated in Palestine from long-past times, and probably in Egypt also. It is the Beta of the Greeks and the far adorem of the Romans, who fully recognized its nutritious qualities. In two of the Old Testament passages above cited spelt is named in close connection with 'wheat,' and the Revised Version renders Isaiah xxviii. 25 as follows: 'Doth he [the husbandman] not put in the wheat in rows, and the barley in the appointed place, and the spelt in the borders thereof?' as if this species were formerly sown as a border round fields of the other cereals. When gathered, the corn was not made into ' shocks' or 'stacks,' but carried to the 'threshing-floor'—an open space beaten flat and smooth. Here the grain was separated from the straw by hand with a flail (Judg. vi. 11; 1 Chron. xxi. 20), or by the feet of oxen (Deut. xxv. 4), or by a heavy cart or dray, either wheeled, or constructed of a heavy slab of wood studded with flints on the under side (Isaiah xxviii. 27, 28; x1i. 15). It was winnowed (xli. 16) by being tossed up with a 'fan' or shovel, and ground by handmills turned by women (Exod. xi. 5; Isaiah xlvii. 2), or in later times by mules or asses (Matt. xviii. 6, R.V. marg.). REED (Heb. קָנֶה kaneh, אָנָם agam; Gr. κάλαμος). 'PAPER REEDS' (Heb. עָוֹת aroth). RUSH (Heb. אַנְמוֹן agmon, נֹּמֶא gome). BULRUSH (Heb. אַנְמוֹן agmon, נֹּמֶא gome). 'FLAG' (Heb. סוּף suph, אַחוּ achu).

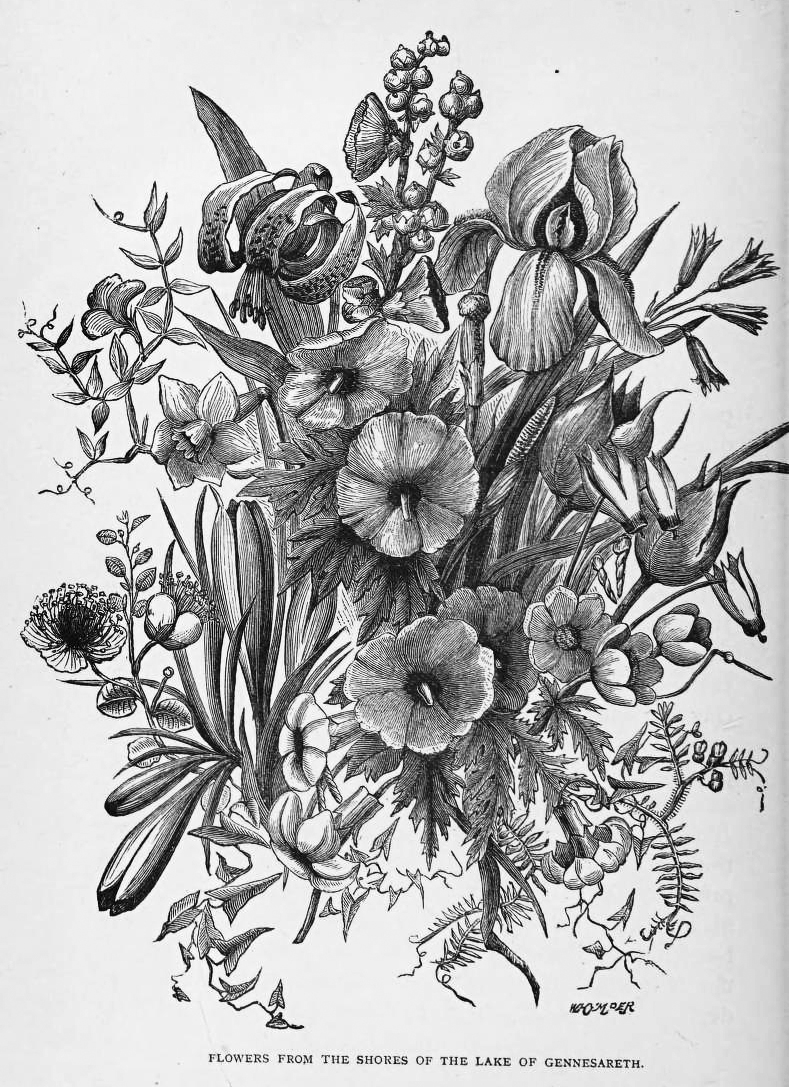

Beside running streams, and especially around the margins of lakes and pools, in damp meadows and marshy places, the familiar types of vegetation known as 'reeds,' 'rushes,' and 'sedges,' grow with more or less luxuriance. They are closely allied to, though distinguishable from, the ordinary grasses; they have a quiet beauty of their own which the microscope further reveals, and are not devoid of economic uses. One in particular, the papyrus or byblus, is indissolubly associated with the history of literature, and has bequeathed to us two of our most suggestive words, ' paper' and 'Bible.' The Rushes (Funcaceae) are distinguished by their fine though inconspicuous flowers. while the Sedges (Cyperaceae) have merely scales, like the 'flower of the grass.' The true Grasses (Gramineae) have rounded and hollow stems, those of the sedge tribe are solid and angular. More than twenty species of rushes, and nearly thirty of sedges, grow in Palestine, including the papyrus. The terms 'reed' and 'cane' are applied to the stems of various grasses and sedges. 'Flag' is a name now restricted to the genus Iris, represented in our gardens and river-sides, but quite distinct from the plants so translated in the Authorized Version. The usual term for a REED is קָנֶה (kaneh) in the Hebrew; equivalent to the κάλαμος of the Greeks and the calamus of the Romans. It is no doubt as general in its application as the English synonym, giving a title to 'the brook of Kaneh,' one of the boundaries of the tribe of Ephraim (Josh. xvi. 8), and including the 'sweet cane' of Isaiah xliii. 24, noticed in Chapter VI. The fragility, pliancy, and instability of these humble forms of vegetation furnish the sacred writers with striking emblems of spiritual truth; and the bruised and broken reed, and ' reed shaken with the wind,' are metaphors as familiar to Bible readers as the objects from which they are derived. A still more general term, אָנָם (agam) is rendered 'reeds' in Jer. li. 32 (R.V.),'The passages [fords, of Babylon] are surprised, and the reeds are burned with fire.' The same word is rendered 'pool of water' in Ps. cvii. 35 and cxiv. 8 (R.V.), where it is obvious that mere plants cannot be meant. It would seem therefore that agam may mean simply either a standing water or the vegetation which usually fringes such pools. The marginal rendering 'marsh' is thus fairly correct. It may be added that this latter word occurs only in Ezek. xlvii. 11: 'But the miry places [of the Ghor] and the marishes thereof, shall not be healed,' apparently with reference to the salt marshes at the southern end of the Dead Sea. The rendering 'PAPER REEDS' in Isaiah xix. 7 would be specially noteworthy if there were anything in the original to sustain it; but the Revisers translate, on better grounds, as follows: 'The meadows by the Nile, by the brink of the Nile, and all that is sown by the Nile, shall become dry.' As to the papyrus, that most interesting plant has disappeared from Lower Egypt; but if included in the prediction of the prophet it is in the preceding verse, where we read 'the reeds and flags shall wither away;' the former term קָנֶה (kaneh) comprehending grasses and sedges, and the latter (suph) all other aquatic vegetation. This term FLAG is also unfortunately perpetuated in the Revised Version of Exod. ii. 3, 'she laid it in the flags.' Its meaning is simply 'weeds,' including alike sea-weeds and those growing in fresh water. Thus, the prophet Jonah says in his prayer: 'The weeds (suph) were wrapped around my head' (ch. ii. 5); the He-brew name of the Red Sea is always 'Sea of Weeds' (yam suph), and the infant Moses was laid in his 'bulrush' cradle among the water-weeds of the Nile. Equally unfortunate is the rendering of another word אַחוּ (achu) in Job viii. 11: 'Can the flag grow without water?' The same word occurs in Gen. xli. 2, where Pharaoh saw in his dream cattle 'feeding in a meadow (achu).' The term is probably Egyptian, and we may accept the assertion of the ancient commentator St. Jerome, who explains it as meaning' all marshy vegetation.' The Revisers have rendered the latter passage 'fed in the reed grass,' and would have done well to transfer a like rendering of Job viii. 11 from the margin into the text. It is, however, rather in marsh grass than reed grass that cattle would find pasturage. We come now to the terms RUSH and BULRUSH, where two words are thus indiscriminately translated in the Authorized Version. The first, אַנְמוֹן (agmon), occurs thrice in the book of Isaiah:— 'The Lord will cut off from Israel head and tail, branch and rush' (ch. ix. 14); the same figure is repeated in ch. xix. 15; and in the more familiar passage (ch. lviii. 5), 'Is it to bow down his head as a bulrush?' A lowly grass, with drooping plume, is evidently intended. In Job xli. 2, it is rendered hook,' and in verse 2o, still more strangely, 'caldron,' but in the Revised Version '(burning) rushes.' Dr. Tristram inclines to think that the Arundo donax — a splendid cane growing abundantly beside the Jordan and the Dead Sea, forming impenetrable thickets, and reaching a height of ten or twelve feet—is the reed of Scripture. But though it may be the 'reed shaken with the wind,' a less conspicuous grass or sedge seems indicated by the prophet in the passages above quoted, and it appears safer to take the word in a less specific sense, just as poets speak of:

'Green rushes and sweet bents'

without any attempt to distinguish the precise genus or species. The prophet

contrasts the 'branch' of some tall or spreading tree with the humble ' rush,'

growing beside the shady pool or running stream. The other word נֹּמֶא (gome) occurs in Exod. ii. 3, where cradled of the infant Moses is said to have been of bulrushes,' 'daubed with slime and pitch;' in Isaiah xviii. 2, where the Ethiopians are spoken of as sending ambassadors by the sea even in vessels of bulrushes upon the waters; and in Job viii. ii, 'Can the rush grow up without mire?' To this last question corresponds the prophetic use of the same term in Isaiah xxxv. 7: 'In the habitation of dragons [R. V. jackals], where each lay, shall be grass with reeds and rushes.' The first two references appear to point distinctly to the papyrus of Egypt; the third has in all probability a similar reference, since Egyptian imagery is frequent in the Book of Job, showing that the writer was well acquainted with that country. Isaiah also, as just seen, was acquainted with the papyrus, and if it grew in Palestinian waters in his day, as it does now, there would be no need to insist on a more general meaning. The Revisers have shown much judgment and taste in the introduction of this un-Biblical word 'papyrus.' In the children's favourite story Moses is still cradled in bulrushes,' the correct term being given in the margin. In Isaiah xviii. 2, 'papyrus' is inserted in the text, while in xxxv. 7, the generic form 'rushes' is retained. In Job viii. 11, papyrus is given as an alternative. This interesting plant (Papyrus antiquorum) is a tall green sedge, with a large and drooping panicle or tuft of florets springing from a sheath at the top. It reaches a height of from ten to fifteen feet, with a diameter of from two to three inches at the base. It had various economic uses, as Pliny and other writers have shown; though, as the Egyptians cultivated other sedges, it is probable that these became more exclusively used for food and fuel, sails and cordage, baskets and sieves, not to speak of the punts or canoes to which the prophet refers and which other writers specially mention. 'The right of growing and selling the papyrus became a government monopoly,' says Sir G. Wilkinson; and it was carefully cultivated, especially in certain districts of Lower, and probably of Upper Egypt also, for the great and important purpose with which its name must ever be associated. For this manufacture the rind was removed, the pith cut in strips and laid lengthwise on a flat board, their edges united by some glue or cement (Pliny says 'Nile water'), and the whole subjected to pressure, compacting the several strips into one uniform fabric. This material, it need scarcely be remarked, was well known to the ancients, and continued to be used in Europe until the time of Charlemagne, when it was superseded by parchment. It is remarkable that although we have no trace in Scripture of the use of papyrus or other vegetable substance by the Jews for writing purposes, the plant has been found to exist in vast quantities in the Lake Merom, as already noted, at the northern end of the Lake of Tiberias, and in some of the streams which flow into the Mediterranean. On the other hand, it has disappeared from Egypt, where it once grew in myriads. It is grown also in Sicily and Sardinia, but on a limited scale. Of the papyrus, or some allied species of sedge, Heliodorus relates that the Ethiopians made swift-sailing wherries, capable of carrying two or three men each; and the traveller Bruce refers to a similar use of this ancient plant among the modern Abyssinians. Other writers give similar testimony, and it is highly probable such light vessels were coated with bitumen, like the rude basket made by Jochebed for her endangered infant. 'TARES' (Gk. ζιζάνια)

The word incorrectly rendered 'tares' occurs only in the New Testament, in the parable to which it has given a title. It is not a classical term, but is supposed to be a Grecized form of a local name. The Arabs still give the name of zirwan to a noxious grass which is only too common in the corn-fields of Palestine, simulating the wheat when undeveloped, though easily distinguish-able when ' both have grown together until the harvest.' This plant is the DARNEL of the agriculturist and the Lolium temulentum of botany. It is by no means unknown in our own country, though somewhat local in its distribution. Mr. Grindon says: 'At Mobberley, in Cheshire, it is so exceedingly abundant; that in a single walk through the fields a large sheaf may be collected. . . . The country people thereabouts believe it to be degenerated wheat.' A similar idea anciently prevailed in reference to oats, but both are erroneous. Shakespeare has not overlooked this intruder:

'Darnel and all the idle weeds that grow In the East it is a more serious enemy to the farmer; and in the low-lying districts of the Lebanon and other parts of Palestine it becomes alarmingly plentiful. If inadvertently eaten it produces sickness, dizziness, and diarrhoea. 'In short,' remarks Dr. Thomson, 'it is a strong soporific poison, and must be carefully winnowed, and picked out of the wheat, grain by grain, before grinding, or the flour is not healthy8.' The parable of our Lord is true to the life and experience of the present time in the land in which He dwelt, except that a deliberate sowing, from 'malice aforethought,' of this wild grass, is not known to residents in modern Palestine. Yet it would seem, strangely enough, to be not altogether out of date nearer home. Turning over the pages of an old newspaper some years since, the writer met with the following paragraph: "The country of Ill-will" is the by-name of a district hard by St. Arnaud in the north of France. There, tenants, when ejected by a landlord, or when they have ended their tenancy on uncomfortable terms, have been in the habit of spoiling the crop to come by vindictively sowing tares, and other coarse strangling weeds, among the wheat; whence has been derived the sinister name in question. The practice has been made penal, and any man proved to have tampered with any other man's harvest will be dealt with as a criminal.' Darnel was known to the ancients under the Greek name of αἆρα and the Latin one of lolium. Virgil9 speaks of 'unlucky darnel,' and groups it with thistles, thorns, and burs, among the enemies of the husbandman.

|

|

|

|

|

1) See Hehn, Wanderings of Plants and Animals. 2) Handbook of Palestine. 3) Il. lib. xiii 4) Virgil, Ecl. ii. 10, II, speaks of garlick and thyme as refreshing the reapers after their toil. 5) De Candolle (Origin of Cultivated Plants) thinks the shallot a mere variety of the onion, and less ancient than is usually supposed 6) In the parallel narrative in 1 Chr n. xi. the field is described as sown with barley (ver. 13). As lentiles are occasionally sown among other plants both statements may be literally accurate. There are, however, other verbal discrepancies in these chapters. 7) Virgil bids his husbandman 'not to despise the care of the Pelusian lentile.' Georg. lib. 8) The Land and the Book. 9) Georg. lib. i. 151-4

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD