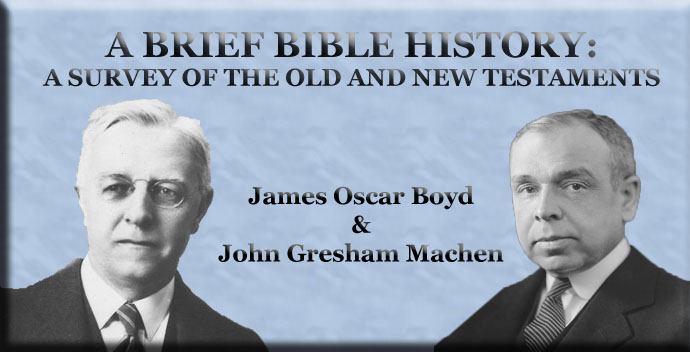

A Brief Bible History:

A Survey of the Old and New Testaments

By James Oscar Boyd & John Gresham Machen

Section I - Lesson XI

Judah, from Hezekiah to the ExileII Kings, Chapters 18 to 25 ; II Chronicles, Chapters 29 to 36; Isaiah (in part); Nahum; Habakkuk; Zephaniah; Jeremiah; Lamentations; Ezekiel, Chapters 1 to 32Although outwardly Judah appeared to be the same after the fall of the Northern Kingdom as before, it was not so. A very different situation confronted Hezekiah from that which had confronted his father Ahaz when he called on Assyria for help against Syria and Israel. Now there were no "buffer states" between Assyria's empire and little Judah. And it was only a score of years after Samaria fell when Jerusalem felt the full force of Assyria. Sennacherib, fourth in that remarkable list of the six kings1 who made Nineveh mistress of Asia, sent an army to besiege Jerusalem, with a summons to Hezekiah to surrender his capital. A different spirit ruled this king. Isaiah, the same great prophet who had counseled Ahaz to resist Pekah and Rezin but had failed to move him to faith in Jehovah, found now in Ahaz's son a vital faith in the God of Israel in this far sorer crisis. In reponse to that faith Isaiah was commissioned by God to assure king and people of a great deliverance. The case, to all human seeming, was hopeless. But the resources at God's disposal are boundless, and at one blow "the angel of Jehovah" reduced the proud Assyrian host to impotency and drove them away in retreat. II Kings 19:35. Scribes who record the achievements of ancient monarchs are not accustomed to betray any of the failures of their royal heroes. But between the lines of Sennacherib's records we can read confirmation of the Bible's report of some great catastrophe to Assyrian arms. Jehovah rewarded the faith of his people in him. The seventh century before Christ, which began just after this event, witnessed both the rise of Assyria to its greatest height, and its sudden fall before the Chaldeans, a people from the Persian Gulf, who succeeded in mastering ancient Babylon and in winning for it a greater glory than it had ever known in former times. Even in Hezekiah's reign these Chaldeans, under their leader Merodach-baladan, were already challenging the supremacy of Nineveh, and in doing so were seeking allies in the west. When the king of Judah yielded to the dictates of pride and showed to these Chaldean ambassadors his treasures, Isaiah announced to him that the final ruin of Judah was to come in future days from this source, and not from Nineveh as might then have been anticipated. Manasseh, Hezekiah's successor, was indeed taken as a captive to Babylon for a time, but the captor was a king of Assyria. II Chron. 33:11. Manasseh was thus punished for his great personal wickedness, for he is pictured as the worst of all the descendants of David, an idolator and a cruel persecutor. Yet his reign was long, and at its close he is said to have repented and turned to Jehovah. But this did not prevent his son Amon from following in his evil ways. A revolt of the people within two years removed Amon, however, and set his young son, Josiah, upon the throne. Josiah's reign is important for the history of Judah. By putting together all that can be gleaned from Kings, Chronicles, and the prophets, it can be seen that Josiah gradually came more and more under the influence of the party in Judah that sought to purge the nation of its idolatry and bring it back, not merely to the comparatively pure worship and life of Hezekiah's and David's days, but to an ideal observance of the ancient Law of Moses. The climax in the progressive reformation in Judah was reached in Josiah's eighteenth year, 622 B.C., when the king and all the people entered into a "solemn league and covenant" to obey the Law of Moses both as a religious obligation and as a social program. The Law book which was found while workmen were restoring the Temple passed through the hands of Hilkiah, the high priest, who therefore committed himself, together with the priests, to this reform. And what the true prophets of Jehovah thought of it may be seen, for example, from Jer., ch. 11, which tells that this prophetic leader preached in the streets of Jerusalem and through the cities of Judah, saying. "Hear ye the words of this covenant, and do them." Josiah attempted to attach to Jerusalem all those elements in the territory of the former kingdom of Israel which were in sympathy with Jehovah's Law, and at Bethel itself he defiled the old idolatrous altar and slew its priests. In fact, it was on northern ground, at Megiddo, that Josiah met his tragic end and the new wave of patriotic enthusiasm was shattered, when, in battle against Pharaoh-necho and a great Egyptian army, the king of Judah was killed. Josiah's four successors were weak and unworthy of David's line. After Jehoahaz, the son whom the people put on the throne to succeed Josiah, had been removed by Necho, Jehoiakim, another son, reigned for eleven years. He owed his throne to the Pharaoh and was at first tributary to him. But early in his reign came the first of many campaigns of the Chaldeans into Palestine, as Nebuchadnezzar, master of Asia, extended his power farther and farther south after crushing the Egyptians at Carchemish in 605 b.c. Jehoiakim had to bow to Nebuchadnezzar's yoke and seems to have lost his life in a fruitless attempt to shake it off. A great number of the leaders of Judah, nobles, priests, soldiers, and craftsmen, were deported, together with Jehoiachin, the young son of Jehoiakim, who had worn the crown but three months, 598 b.c. For eleven years more, however, the remnant of Judah maintained a feeble state under Zedekiah, a third son of Josiah and the last of David's line to mount the throne. In spite of his solemn oath to the king of Babylon and in the face of the express warnings from Jehovah through his prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel, this weak and faithless king revolted from Babylon, put his trust in the Egyptian army, and prepared to stand a siege. But Jerusalem's end had now come, as Samaria's had come before, and through a breach in the northern wall the Chaldean army entered; the king fled and was captured, blinded, and deported, and the whole city, including houses, walls, gates, and even the Temple — that famous Temple of Solomon which had stood nearly four centuries — was totally destroyed, 587 b.c. All that remained of the higher classes, together with the population of Jerusalem and the chief towns, were carried away to Babylonia, to begin that exile which had been threatened even in the Law, and predicted by many of the prophets, as the extreme penalty for disobedience and idolatry. __________ 1) Tiglath-pileser, 745-727 B.C.; Shalmaneser, 727-722; Sargon, 722-705; Sennacherib, 705-681; Esar-haddon, 680-668; Ashurbanipal, 668-626. |

|

|

|

QUESTIONS ON LESSON XI1. How did the fall of Samaria affect the Kingdom of Judah? 2. How did Hezekiah meet the threats of Sennacherib? What was the outcome? 3. Which king carried through a reformation of religion? What was the basis of the covenant he imposed on Judah? How did he meet his end? 4. Describe the relations of the Chaldeans to Judah in the time of Hezekiah, of Jehoiakim, of Zedekiah? 5. When did Jerusalem fall? Did it fall unexpectedly and without warning?

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD