Paul Before Agrippa.

By The Reverend W. H. P. Faunce,

New York City.

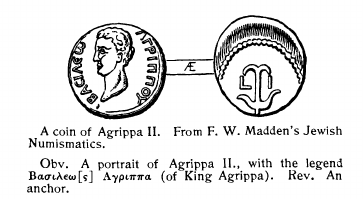

He is a chosen vessel unto me, to bear my name before kings." Such is the divine description (Acts 9:15) of the career which opened to Saul of Tarsus on the Damascus road. He had already carried " the name" before Jewish Synagogues (Acts 13:16), mobs of frenzied fanatics (Acts 14:5; 17:6; 22:), Roman praetors and procurators (Acts 16:22; 24:10), religious curiosity-seekers (Acts 17:17-22), and now he was to stand before a man who, " dressed in a little brief authority," bore the actual title of " king." We have to study the scene, the dramatis personae, and the apologia itself. 1. The Scene.—The once magnificent city of Caesarea reveals its character in its name. It was the creation and the seat of Roman power in Palestine. That straight coast line, ever jealous of the sea, apparently resenting the intrusion of the smallest bay or gulf, exactly symbolized the attitude of Judaism toward the overshadowing pagan power in the west. There is no word in the Old Testament for "port," and none was needed. But Caesarea, made to order by Herod the Great, marked the official entrance and settlement of the imperial power on the sacred soil. If the book of Acts relates the progress of the gospel from Jerusalem to Rome, Caesarea, in whose streets mobs of Jews and Gentiles often contended, lies in the center of the story. There Herod created a splendid harbor by throwing out a breakwater 200 feet wide, sinking enormous stones into the deep sea, a few of which are still left to interrupt the monotonous plashing of the waves on the deserted shore. There Herod erected, on raised ground, palace and temple, and theatre and amphitheatre, whose walls of white limestone gleaming in the sun were visible far out to sea. There he built the huge drains of which Josephus speaks. To the Jews Caesarea was the gateway of Rome; to the Romans it was, so to speak, the handle of Palestine. Here Paul for two whole years was perfectly safe, when in Jerusalem he could not have lived a day. Farther down the coast lay intensely Jewish Joppa, orthodox and fanatical. But in Caesarea lived Cornelius the centurion who combined the worship of Jehovah with loyalty to Rome, and in Caesarea Peter with sudden accession of light cried out: "I perceive that . . . in every nation he that feareth him, and worketh righteousness, is acceptable to him." Here also lived Philip the evangelist who dared to preach to the Samaritans (Acts 8:5), and to baptize the Ethiopian treasurer (Acts 8:38). Did enlargement of view come to the apostle himself during his two years' residence under Roman detention and protection ? The contrast between the letters to the Thessalonians and those to the Colossians and the Ephesians is the answer. Did he often pace up and down the battlements of the palace, gazing out over the western sea toward the churches whose " care " was upon him daily ? However he might chafe against the law's delay, he at least realized that he was safer in pagan hands than among worshipers of Jehovah ! " Caesarea was heathenism in all its glory at the very door of the true religion! Yes, but the contrast might be reversed. It was justice and freedom in the most fanatical and turbulent province of the world. In seeking separation from his people and an open door to the west, Herod had secured these benefits for a nobler cause than his own."1 Amid such surroundings Paul was summoned into the "audience chamber" of the palace to speak before Agrippa. It was not another trial, no accuser was present. It was rather a preliminary investigation or examination (ἀνάκρισις) in order that Festus who honestly confessed his perplexity (ἀπορούμενος δὲ ἐγώ) might avail himself of Agrippa's " expert " knowledge of Jewish affairs, and have something definite to write to his "lord " at Rome (Acts 25:26). With lavish display and true oriental pomp the procession streamed into the audience chamber, Festus, Agrippa and Bernice leading the way. Then followed the chiliarchs of the large garrison, resplendent in color and gleaming in helmets and coats of mail, and finally the chief citizens of Casarea, who wished to see the spectacle of royalty if not to hear the apostle. Before such an assembly, brilliant with military uniforms and royal robes, with the flashing of spear and shield and long obsequious retinue, the chained prisoner of the Lord was now led in. Was he familiar with the consoling word of Jesus: "Be not anxious how or what ye shall speak; for it shall be given you in that hour what ye shall speak ?" (Matt. 10:19.) As Festus was thinking of his " lord " and eager to please him, Paul was thinking of his. The difference in the men was really the difference in their " lords." II. Of the chief persons concerned in this parade of authority we possess considerable knowledge. Porcius Festus, who had just become procurator (A. D. 60), and who died the year following, was a comparatively pure and upright man, and (like most of the Roman officials in the book of Acts) appears to great advantage in the story. Unlike his miserable predecessor, Felix, he did not take bribes to prevent justice. Immediately on entering office he is beseiged by the demand of the Jews that Paul be sent to Jerusalem for trial, but with wise caution refuses. He seems to have been prompt in action (" after three days," Acts 25:, " on the morrow," 25:6, " I made no delay," 25:17,) resolute at least on occasion (" it is not the custom of the Romans," 25:16) and declares that to send this prisoner to Rome without evidence of guilt would be absurd (ἄλογον). He recognizes the genuine manliness of the apostle (ἀνήρ, he calls him, while Agrippa says ἄνθρωπος), and declares that he has committed nothing worthy of death. With fine scorn he speaks of all this tumult of the Jews as merely a discussion of "certain questions of their own superstition," and declares that the whole uproar seems to be "about a certain Jesus, a dead man, whom Paul affirmed to be living still." Agrippa II., son of the Agrippa I. who perished so miserably in this very city (12:23), and great grandson of Herod the Great, was worthy of his ancestors, and like them a suppliant for the favor of the Jews on the one side and the Romans on the other. The voice of Rachel weeping for the innocents of Bethlehem, and the superstitious fears of his great uncle who murdered John the Baptist, might well haunt the dreams of Agrippa II. When his father died the young prince was but seventeen years of age, and was therefore kept for a time with Claudius at Rome, while various procurators did their best to curb and govern the fiery Jewish temper. In A.D. 48 he became ruler of the little province of Chalcis, with power to nominate the High Priest and to superintend the temple in Jerusalem. In A.D. 52 he acquired also the tetrarchies of Philip and Lysanias, and the coveted title of king. His religion was the cloak to his ambition, and his cynical answer to Paul's burning appeal makes us wonder how the apostle could say:" I know that thou believest." Was the ardent wish the father to the thought ? Certainly the man who could aid Vespasian and Titus in the destruction of Jerusalem did not " believe the prophets in any way that could mould his life." Bernice, the sister of Agrippa, and sister of the adulterous Drusilla as well, had since the death of her husband lived with her royal brother, "not without suspicion of infamy," says Tacitus. To her the whole scene in the Caesarean palace, and the address of Paul may well have been the novelty and recreation of a leisure hour, a curious but meaningless performance. III. The address itself proceeds as follows:

However much room we allow in the report of this speech for the embellishments of the reporter, the composition yet bears the vivid impress of original fact. It is the most valuable summary of the apostle's life and his relation to his mission which we possess. In this address he was not disturbed by any howling mob as in the " speech on the stairs " (Acts 22:22), but was heard courteously until he neared the end. He was not seeking to divide a jury against itself, as in Acts 26:6. He was not pleading for his life. All allusions to himself are simply to make it clear that he is no criminal, but is pursuing a course from which Rome has nothing to fear, and in which Judaism ought to see its own realization and fulfilment. A few characteristics of the address we may note. It clothes its bold conviction in forms of exquisite courtesy. Urbanity is not an Old Testament virtue. Israel's greatest prophets were children of the wilderness, scorning the soft clothing of kings' houses and the conventionalities of courts. Moreover, Paul was himself by nature "proud, unbending, unsociable, self-assertive, a strong soul, invading, enthusiastic" (Renan). But here without a trace of flattery, he declares himself "happy" to stand before Agrippa, and in his most impassioned moment does not forget the official title of Festus, " your excellency " (vs. 25). Not a word of accusation or reproach does he utter. The same tenderness appears as when he arrived at Rome—"not that I have aught to accuse my nation of." The whole narrative is sharp and vivid, and filled with picturesque detail. Paul "stretched forth his hand," the hand which had so often ministered to others' necessities (Acts 20:34), the hand which wrote in great black letters the closing sentences to the churches of Galatia (Gal. 6:11). In the conditional form "If God doth raise the dead" (vs. 8), we seem to hear the very echoes of the great debate. The apostle pictures his own revengeful feeling (τιμωρῶν). Every detail of the great Christophany is imprinted on his mind. He was journeying to Damascus "on this errand;" the time was " at the middle of the day;" the sudden light was "above the splendor of the sun" and was shining "along the road;" immediately they were " all fallen down " and the voice spoke "in the Hebrew dialect." This whole passage is full of Hebraisms and bears the stamp of reality. The apostle declares that his Christianity originated not from his " much study" (vs. 24) not from cunning argument, not from human authority, but in an immediate revelation of the risen Lord. The nature of the heavenly vision, and its relation to the appearances to the other disciples cannot here be discussed. The difference between a faith founded on logic or on documents and the Pauline faith is obvious. Throughout the address Paul insists with tremendous earnestness that his new faith is harmonious and indeed identical with the original faith of Judaism. The "twelve tribes earnestly serving God night and day," are seeking the Messiah, and Paul has found what they seek. He cries in amazement:" Concerning this hope I am accused by Jews, O king !" "After the most rigid party in the natural worship" Paul had lived " from his youth up," and is now preaching " nothing but what Moses and the prophets did say should come." How to reconcile this with the apostle's scornful allusions to the law as "weak and beggarly elements" and his perception of the absolute opposition between Judaism and Christianity is an interesting question. Did he here become " to them that are under the law as himself under the law ?" (1 Cor. 9:20.) But in 1 Tim. 1:1, Paul affirms that the faith of Timothy is essentially that which dwelt also in Lois and Eunice. So emphatic does Paul become that at length Festus (whom the apostle was not addressing at all) bursts out:" Paul thou art mad" (hast a mania); thy many studies (in Moses and the prophets) have turned thy head." Again Paul asserts the publicity of the facts—"the whole history was not done in a corner," as the king well knows. Then Agrippa speaks with an ironical smile: "With a little effort thou art perhaps persuaded thou canst make me a Christian!" Doubtless the smile passed round the bejewelled circle of royalty and the assertion of eternal truth was answered with a jest. Then followed the lofty answer of the apostle, and the ruthless king broke up the sitting. Thus we have in this chapter the noblest address of the Acts, courteous, graphic, tremulous with personal conviction, affirming that Christianity, instead of being at war with previous divine revelation, a break with history, and the grand exception to law, is the culmination of all the past and the answer to the prayers of the fathers, and is " both to small and great," "to the people and to the Gentiles" the power that throughout the world and the ages can turn men "from darkness to light and from the power of Satan unto God."

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1) The Historical Geography of the Holy Land, p, 141, by George Adam Smith.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD