The Synoptic Problem

Part 6 of 14

By J. F. Springer, New York

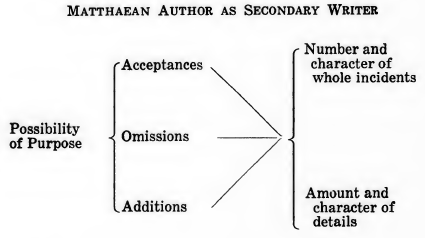

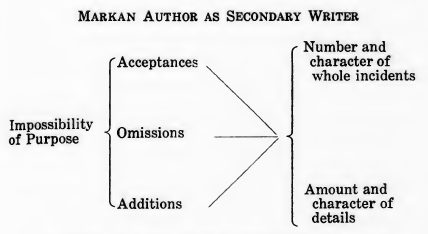

An Inquiry Into Parallelism And Non-Parallelism Between Matthew And MarkThis is not the place, perhaps, to enter upon an extended exposition of the requirements imposed by logic for the control of efforts directed to the establishment of hypotheses. At the same time, in view of the situation at the stage of our examination at which we have now arrived, it seems not undesirable to make inquiry as to what principles should govern our further investigation of the significance, with respect to sequence of derivation, that is to be attached to the phenomena which may roughly be summed up under the phrase, the “absorption” of Mark. Those writers who have participated in the development and interpretation of the facts pertaining to order of events, a research covering a period of eight or nine decades, do not seem to have conducted their work under the guidance and restriction of adequate rules. Otherwise, they would hardly have concluded that the facts of order require us to believe that our First Gospel is a derivative of the Second. All this we have had before us in very considerable detail. And we have also taken up the matter of the “absorption” of Mark and made a preliminary inquiry into it. It is now proposed that we continue the investigation by a sufficient presentation of the details with the view of ascertaining whether the evidence and arguments presented by advocates of Matthaean dependence may be developed to such a point as to make it possible still to maintain their claim. The old presentation does not warrant its maintenance; but perhaps a full and adequate research will show it to be right and proper. It appears to me that all our inquiries ought to be controlled by this same spirit. We should seek not merely the conclusion proper in view of the facts and arguments as advanced by opponents: we should prosecute the matter further with the object of ascertaining whether a sufficient, as compared with an inadequate, inquiry will not rehabilitate the claim we oppose. That is to say, our purpose ought to be directed to an uncovering of the truth rather than to a downing of antagonists. Accordingly, the proper question is not merely whether the advocates of the derivation of Matthew from Mark have made a success of their efforts. There should be a broader outlook. We should seek to ascertain whether the fuller development of the phenomena belonging to any given class will not resurrect a claim otherwise found to be dead. The reader who has worked through my pages devoted to the argument from order,1 may perhaps have noted that what I had broadly in view was not merely to answer what opponents had set forth, but quite as much to discover whether, in any way, the line of argument could be developed so as to warrant the conclusion I was opposing. This same purpose should, I think, still be maintained. Those who have advocated the proposition that the facts concerning the “absorption” of Mark justify the claim of a Matthew secondary to this Gospel may have failed. The question now to be considered is whether a thoroughgoing inquiry will not show that in spite of the breakdown they were nevertheless on the right track. The situation as outlined makes pertinent, if indeed it does not make necessary, a brief presentation of principles that should control our further inquiry. An hypothesis is a proposed explanation. It seeks to set forth the cause which is not only competent to produce the facts to be explained but which did actually produce them. It will not always be possible to establish in a direct manner the actuality of the proposed cause. However, an indirect effort may frequently prove successful. We can always assume that the group of facts must have had its proper cause. If then we are able to ascertain not some but all of the possible causes competent to produce these facts and in addition to follow up this exhaustive inquiry by the elimination of all but one, we may at once say that this remaining competent cause must have been the actual cause at work. If this programme is carried out with sufficient rigor in all details, the result is an effective demonstration that the hypothesis is true which proposes this uneliminated competent cause. I conceive that any successful attempt to solve the Synoptic Problem will limit itself very closely to this procedure. The investigation which has been going on for so considerable a period of time and which has reached the conclusion that Matthew is a derivative of Mark has singularly failed to keep before it certain necessary principles involved in the programme which I have set forth. Thus, the facts to be explained by the hypothesis of a Matthew derived from Mark are to be understood as having reference to all the phenomena affected by this assumption. For example, we have before us at the present time the question of the “absorption” of Mark. If, for the purpose of concluding that Matthew must have been derived from Mark, we are going to use the parallelism and non-parallelism between these two Gospels in an attempt to show that Matthew must have “absorbed” Mark, we are required by logical considerations not to pick and choose amongst the facts, but to consider all the relevant phenomena. It is not permissible to set forth the matter of “absorption” in such way as merely to bring out the fact that with the exception of, say, eight incidents all the events of Mark are represented in Matthew. Such a presentation is seriously inadequate. It is true that if the table of contents of the one Gospel be placed alongside the table of contents of the other it may at once be shown that nearly the whole Markan list reappears in the Matthaean. But this does not signify, by any means, that the import of Mark is duplicated in Matthew. There is, indeed, a very considerable total of information in the Second Gospel that is not to be found in the First. The facts as to this matter are decidedly relevant. When Mark is set up as an exemplar to Matthew, difficulty at once arises in explaining why the Matthaean writer omitted so considerable an amount of informative material. In view of the character and amount of matter contained in Mark but not in Matthew, it is not at all permissible to pay attention merely to the fact that the First Gospel has in its table of contents nearly all the titles in the Markan table and to disregard the other fact that in the text of the Second Gospel is to be found so large an amount of information not discoverable in the First. If, then, we are to get a just view, it will be necessary to deal more adequately with the situation than such writers as B. Weiss, W. C. Allen and Rudolf Knopf seem to have done. We are liable to mislead not only others but ourselves as well when, in dealing with the “absorption” of Mark by Matthew, we say that with the exception of a few sections the First Gospel “presents almost the entire Markan material.” In the Markan sections parallel to Matthaean sections is a relatively large total of supplementary information not contained in Matthew. If, indeed, the First Gospel is a compilation largely dependent upon the Second, the failure to “absorb” available material is a noteworthy difficulty. It will be necessary then to present a balanced exposition of the relevant facts as to parallelism and non-parallelism. And this I propose to do shortly. In the preceding, we considered the presentation of the facts as they would appear when the assumption is made that Matthew is a derivative of Mark. It is practically necessary to go further and deal with the matter of presenting the facts when the alternative assumption is adopted that sets up Mark as a derivative of Matthew. The reason underlying the necessity is that we must consider the possibility of maintaining this alternative hypothesis as a competent cause, in order to determine whether we can convert the hypothesis of the derivative character of Matthew, once it has been shown to be tenable, into an established hypothesis. That is to say, we have at the outset two alternatives—(1) Mark-Matthew and (2) Matthew-Mark. If we succeed in showing that alternative No. 1 is a competent cause, we are still short of our objective. We cannot maintain it as undoubtedly the actual cause, until we have eliminated alternative No. 2 as a competent one. Consequently, we must, whether we wish to do so or not, consider the possibility of maintaining that Mark is a derivative of Matthew. Concerning PurposeWhether we set up the one alternative or the other, we are confronted by the question, What was the purpose of the secondary writer? In either case, failure to find a purpose would be damaging. And, if the negative proposition can be established that maintains that no reasonable purpose is conceivable, we shall have a very destructive consideration. Now, it is perhaps not difficult broadly to conceive why, under the hypothesis of a Matthew derived from Mark, the Matthaean writer might wish to compose his Gospel. The desire to include the Infancy Section, the Sermon on the Mount and a great additional total of discourse material would seem to constitute a sufficient basis for such a purpose. But, how does this matter of reasonable purpose stand, when we make the assumption that Mark is a derivative of Matthew? We need to ascertain what answer can be made to this question, in order that we may determine whether or not it is possible to maintain the tenability of the derivation of Mark from Matthew. In short, we need to consider the facts as to parallelism and non-parallelism as they appear when Matthew is made primary and Mark secondary, because we must determine whether this hypothesis is a competent cause or not in order to learn whether it may or may not be eliminated and its alternative converted from a tenable to an established hypothesis. As a matter of fact, when Matthew is set up as the parent document and Mark as a daughter writing, a very good purpose may apparently be assigned for the composition of the secondary narrative. It seems sufficient to conceive that the writer wished to produce an account limited to the public life of the Savior and to the Resurrection as to its extent, and largely to His deeds as to its content. We are thus able to understand the omission of the Infancy Section and masses of discourse. If, now, the two tables of contents be compared after the removal of these portions of the First Gospel, it will be found that the Markan writer omitted just about the same number of titles as the Matthaean must be conceived as having excluded when we assume the alternative hypothesis as to derivation. Secondly, under the assumption, in the one case, that the author of Matthew wished to treat the infancy period and to include various heavy amounts of discourse, and, in the other case, that the writer of Mark desired to limit his Gospel rather closely to the public life of the Savior, to His works, and to the Resurrection, the two alternative hypotheses as to derivation are to be regarded as upon an equality, in so far as the broad evidence as to unparalleled material is concerned. However, in order that the possibilities of resuscitating the claim for a Matthew derived from Mark may be properly before us, it will be necessary to exhibit in considerable detail the phenomena of parallelism and non-parallelism as they appear when we assume the derivation of Mark from Matthew. The reader may expect in due course a sufficient exhibition of the relevant facts. It is now reasonably clear, perhaps, as to what must be done in our exposition of the facts. That is, it is clear, in so far as amounts of omitted and added material are concerned. What has not been brought to the fore, in any sufficient way, is the character of the textual matter involved in the omissions and additions. This is really important. Thus, in balancing the list of omitted titles, when Matthew is made secondary to Mark, against the omitted titles, when Mark is assumed a derivative of Matthew, we must take into account not merely the number of titles in the two lists but the character of incidents whose titles are enumerated. We are now sufficiently prepared, perhaps, to enter upon the consideration of a detailed presentation of the facts having to do with the argument for Matthaean dependence upon Mark that is based upon the “absorption” of the Second Gospel. It is assumed that one or the other of the first two Gospels is directly dependent upon the remaining one. Of course, this assumption ought to be proved or disproved. Whether this has ever been done is perhaps open to doubt. At any rate, the reader is warned that our discussion is proceeding as if direct dependence were an ascertained fact. From my point of view, it is for the time being a matter of no moment. I am engaged upon destructive, not constructive, work. If it is successful, it makes little or no difference whether the assumption of direct dependence represents a fact or not. Either way, the arguments that Matthews may be proved dependent upon Mark by the evidence of the phenomena of “absorption” continue dead. The business now before us concerns the determination, upon a consideration of all pertinent evidence arising out of parallelism and non-parallelism, whether the inference that Matthew is a derivative of Mark is justified. The mode of procedure is based upon the assumption that one or the other of these two Gospels is parent and the remaining one offspring. The secondary writer must be conceived, then, as having been controlled by some reasonable purpose in accepting material present in his exemplar, in omitting other matter, and in making additions. Whether the Matthaean or the Markan author be viewed as the compiler, the acceptances are represented by the parallel matter. The omissions and additions under the two alternatives are to be found in the unparalleled material of the two Gospels. In order to study the activities of the two writers when successively assumed to be compilers, we must have before us the facts of parallelism and non-parallelism, since these facts are the data from which we infer the purpose at work. From the phenomena of parallelism, we seek to ascertain the motive actuating the compiler in accepting material; and from those of non-parallelism, we endeavor to determine his object in omitting and also in adding matter. These various motives should then be harmonized into a single general purpose. The very object of those whom I oppose, in considering the alleged “absorption” of Mark by Matthew, is to exclude the hypothesis of the derivation of the Second Gospel from the First by making clear that this hypothesis would lead to an impossible purpose. Does the reader fail to hear the advocates of a dependent Matthew say, Why should the Markan compiler set about writing a book that would accomplish very little more than repeat what had already been told? If, in this or some other way, the impossibility of the Markan purpose could be shown, this would constitute an indirect method of establishing the reverse hypotheses; but, because of the fundamental assumption that one or the other of the two alternatives must be true, it is to be conceded that it would be none the less effective. If a real proof of the impossibility can be developed, it will suffice to settle the question before us, and we should in this way learn that Matthew was really derived from Mark. On the other hand, we cannot reach this result merely by showing that a Matthaean compiler might have had a possible purpose. Such a procedure would simply repeat the widespread fallacy of concluding that because a given hypothesis adequately explains the known facts it is therefore true. Accordingly, a proof that the purpose of the Markan writer, when he is conceived as the compiler, is impossible would be conclusive, while a demonstration that the purpose of the Matthaean author, when viewed as a secondary writer, is possible would be inconclusive. As a matter of fact, however, the logical situation developed by investigations in general is often such that an impossibility cannot be established. The evidence falls short of being sufficient. Under such circumstances, it is well to examine into the possibility of the one or more alternatives. And, even if the demonstration of the impossibility be deemed conclusive, the appeal to the evidence that may be adduced for the possibility of the alternatives will do no harm to the cause of truth. It may reveal that we have been hasty in concluding upon the impossibility. In the present case, there is only one alternative. This is the purpose of the author of Matthew when he is made a compiler with Mark before him. In examining into the possibility of this purpose, we will naturally encounter more or less evidence for its impossibility, if there should be such. In case this evidence turns out to be of a weighty character, our plain duty is then to re-examine the evidence that was thought to be conclusive. What we have to do, in consequence of this analysis of the situation, is (1) to search out all evidence having to do with the possibility and impossibility of the existence of a reasonable purpose on the part of the Matthaean writer when he is assumed to have been secondary; and (2) to examine into the evidence for and against the impossibility of a proper purpose having been entertained by the Markan writer when he is viewed as having Matthew before him. Naturally, however, these questions arise: Are we seeking to do something which has already been done? Are we merely duplicating past expositions? Let me say, then, that my acquaintanceship with the manner in which the advocates of Matthaean dependence have sought to use the so-called “absorption” of Mark in Matthew does not encourage the belief that their investigation has ever reached a scientific level—a height from which the whole question of purpose could be seen and the whole body of relevant facts could be discovered and justly interpreted. I suggest, then, that the matter of the “absorption” of Mark has never been adequately studied. In fact, the very phrase, “absorption” of Mark, is a onesided presentation of the matter. We really need to deal with the question of purpose more impartially. We should examine the facts both of parallelism and non-parallelism, and these facts should be considered from the two points of view that come into existence when the two writings are successively made secondary. I propose now to venture upon the task of giving a brief statement of rules which, if conscientiously followed, will result in providing an adequate basis for a proper inference as to the question whether the dependence of the First Gospel can be claimed as shown by the facts having to do with purpose; and which, if not substantially followed, will leave this problem unsolved. That is to say, I propose to set forth rules that are sufficient and in their substance necessary. Since we have to do with purpose, we have to do primarily with the secondary writer. But as both the Matthaean and the Markan writers were conceivably such, we must consider the purpose which each would have had as a compiler. In the case of the Matthaean author, we are concerned primarily in showing that his purpose would have been possible. In the case of the Markan writer, our business is at the outset, to make clear that his purpose would have been impossible. I speak, for the time being, as one who is siding with those whom he opposes. In both instances, the facts to be assembled are the data as to acceptance, omission and addition. In collecting and interpreting these data, we are to give, in connection with each of the three classes, attention to the number and character of incidents considered as wholes, and also to the amount and character of details. I exhibit these requirements diagramatically.2

Number Of Matthaean Acceptances Of Whole IncidentsLet us begin by inquiring into the number of whole incidents which we must view as acceptances of Markan material made by the Matthaean author when we assume him to have been a secondary writer. In the first place, let it be noted that we can by no means be certain that we are in possession of all the Markan narratives accepted, under this hypothesis, by the author of Matthew. That is to say, it is not at all improbable that Mark once contained accounts which are now absent in our copies and versions of this Gospel, but which once existed as parallels of Matthew. The Second Gospel now terminates at 16:8. It is probable, though not certain, that originally the text extended further and contained parallels of one or both of the incidents contained in Mt. 28:11–20. As I have shown elsewhere,3 the Gospel of Mark very probably underwent a mechanical derangement of the first third of its contents. And it is not at all improbable under the assumption of a derivative Matthew, that the derivation was accomplished before the derangement, or at least by the use of a copy unaffected by it. The underranged MS. may very well have contained material now absent in Mark, particularly material belonging to the disturbed part of the text. This means that the Mark which the Matthaean compiler employed as exemplar may very well have contained narratives now absent from our Second Gospel, these having been lost in the accident which occasioned the derangement, but nevertheless now present in the First Gospel. Accordingly, we must view any enumeration of Matthaean acceptances of Markan incidents as quite possibly incomplete, if it takes into account only those narratives in Matthew which have parallels in the present form of our Gospel of Mark. It is, perhaps, unnecessary to tabulate here the long series of Matthaean incidents which are parallels of Markan events and which, under the assumption that the writer of Matthew compiled from the Second Gospel, must be viewed as acceptances made by this author. They may be read, though in the Markan and not in the Matthaean order, from the tabulation on pp. 67-69 of BIBLIOTHECA SACRA for January, 1924. All incidents indicated as in Matthew are to be considered as Matthaean acceptances. The incidents which are now found in that part of Matthew paralleling the first third of Mark (Mt. 3:1—14:12) and which accordingly, under the assumption of a secondary First Gospel, may also very well have been acceptances are the following: Mt. The centurion’s servant. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8:5–13 The two blind men. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9:27–31 The mute demoniac. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9:32–33 [34] John’s messengers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11:2–6 There are other passages in Mt. 3:1—14:12 which may perhaps have had counterparts in the copy of Mark that the Matthaean compiler had in his hands. I omit them because the content in the several cases is mostly discourse.4 As the copy of Mark used by the Matthaean compiler may very well have included material relating to events now to be found only in Mt. 28:11–20, the list of quite possible acceptances is to be increased by the following incidents: Mt. The bribing of the soldiers. . . . . . . . . . . . . 28:11–15 The mountain in Galilee. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28:16–20 Our present Mark contains 83 narrative sections. Matthew parallels 76 of these. That is, if we compare the tables of contents of the two Gospels, we may say that the Matthaean table contains 92 per cent, of all the titles appearing in the Markan. If we include in the acceptances the six events which I have listed in two groups as quite possible, the ratio of Matthaean acceptances to the total list of Mark will not be much changed, since we must not only add the six to the number of acceptances, but also to the number of items in the Markan table of contents. That is, the ratio of 76 to 83 is just about the same as that of 82 to 89. In the one case, we have 91.56 per cent, and in the other 92.13. In fact, even if we add the five sections listed in the footnote, we will obtain 92.55 per cent, for the ratio of 87 to 94. Of the whole number of Markan titles, the percentage accepted by the Matthaean compiler is, accordingly, about 92, whether the Mark used as exemplar was larger than what we now possess or not. It will be well, perhaps, to pause a moment at this point and consider the situation as it exists before the introduction of further evidence. The result that the Matthaean table of contents contains 92 per cent, of the topics in the Markan table is a definite statement of the facts which B. Weiss, W. C. Allen and Rudolf Knopf sought to indicate when they used such language as the following:

The expression “92 per cent.” is definite because it states accurately the proportion of the Markan series of whole incidents. If we say, “all but seven” or “all but eight,” this is more or less vague, because we fail to take account of the total number in the Markan series. Nor would the vagueness be eliminated by saying “almost all,” because of the indefinite character of the word almost. This expression, “92 per cent.,” then, is to be preferred. The questions may now be raised, What is the logical significance of the fact that the Gospel of Matthew treats 92 per cent, of all the topics treated in the Gospel of Mark? Does this fact decide which of the two documents is secondary? That is, Is it consistent with the purpose of a secondary Matthew and inconsistent with that of a secondary Mark? I answer at once that no decision is reached. The fact as to the 92 per cent, is ambiguous. It does permit us to maintain that Matthew is secondary, since it is reasonable enough that a secondary writer should accept an exemplar’s choice of topics to the extent of 92 per cent, of the whole number. But, it is also permissible to view a secondary writer—as the Markan, when the Second Gospel is made the derivative document —as so dependent upon his exemplar for his selection of topics that he treats no others in 92 per cent, of his entire number. Accordingly, we learn nothing at all with respect to the point in which we are interested. We are still unable to decide which of the two Gospels is secondary. Character Of Matthaean Acceptances Of Whole IncidentsBut, we have by no means exhausted the possibilities of evidence, though we are still able to view the situation as in accordance with a reasonable purpose when Matthew is made secondary to Mark and is in consequence seen to have accepted 92 per cent, of the titles treated by the parent document. The questions that now come to the fore are these: What will be the effect of taking into account the character of the narratives accepted by the Matthaean writer? Will the purpose of a secondary Matthaean writer continue to be a reasonably possible one? Our diagram indicates this as a proper matter of inquiry, directing us, as it does, to the consideration not merely of the number of incidents accepted but of their character as well. It will be proper to begin by paying attention to the matter of miracles. Accounts of miracles abound in both Gospels. If we disregard general statements of miraculous works and note only specific cases, the two documents stand almost upon equality with respect to the number described, Matthew containing two or three more accounts than Mark. In general, the miracles recounted in the one writing are also set forth in the other. The exceptions are listed in the accompanying table, the Infancy Section of Matthew not being taken into account.

The narratives of the miracles are not always coextensive with the account of the event with which they are associated, and in a couple of cases one description is imbedded in another. Thus, the narrative of The blind and mute demoniac (Mt. 12:22) really provides the introduction for the discourse as to the divided house; and the account of The woman with the issue of blood (Mt. 9:20–22; Mk. 5:25–34) is, in both Gospels, really imbedded in the description of the miracle of The ruler’s daughter (Mt. 9:18–19, 23–26; Mk. 5:22–24, 35–43). Accordingly, in matching accounts of miracles in the two Gospels, we will not always be matching narratives of whole incidents. Matthaean Abridgments Of MiraclesWe are now prepared, perhaps, to enter upon the consideration of a very remarkable fact having to do with the matter of Matthaean acceptance of Markan incidents. There are no less than fourteen instances of miracles in recounting which the Markan narrative is fuller than the Matthaean. That is, on the assumption of a derivative First Gospel, we must concede, in all fourteen cases, that the writer of this document cut down the amount of space given to the account in his exemplar. I tabulate the narratives and give the exact space, as indicated by the number of words, occupied in the respective Gospels.5 Viewing the writer of the First Gospel as a compiler working with the Second Gospel before him, we are required to note that he cut down, in narrating these fourteen miracles, a total of space amounting to 2,089 words to one amounting only to 1,211. He told, in the several cases, a lesser history, one which was, on the average, only about 58 per cent, of the history in front of him.6 We are by no means to understand that the Matthaean compiler condensed verbose accounts and retold the incidents in such way as to present the same import in fewer words. This is not at all the case. The reduced space is attained by omission of details. The resulting narrative tells a lesser history. It is absurd to view the two styles as so related that the Matthaean writer communicates the same import in a reduced number of words. The differ-

ence in style, if any, is practically negligible. The Markan author uses, now and again, expressions that are more or less tautological. He will, for example, write “in the wilderness” immediately after having written “into the wilderness” (Mk. 1:12–13), when he could have used simply an adverb signifying there, and thus have reduced his number of words by two. In Mk. 1:28, he could perhaps have omitted “all.” In Mk. 1:32, we find “at even, when the sun did set” (six Greek words). Matthew at the corresponding point (Mt. 8:16) has “when even was come” (two Greek words). If there were multitudes of such cases, a substantial difference in compactness of style would result. But there are not multitudes—only here and there a case. The reader may expect that later on a fuller exposition will be given of the fact that, in general throughout Mark, in connection both with miracles and with other matters, when the text recounts an incident in a greater number of words, this means that additional details are being presented. Those, then, who think that the Gospel of Matthew is a derivative from the Gospel of Mark have to face the broad fact that, in so large a proportion7 of the total number of instances where

the compiler recounts a miracle found in his exemplar, he reduces the material available to him to such an extent that he presents on the average only about three-fifths of the import. The abridgments occur, say, in 14 out of a total of 19 cases; so that we find that the average reduction to three-fifths of the history before him was carried out in nearly three-fourths of all instances where the compiler of the First Gospel accepted a miracle from the Second. The suggestion that the author was struggling to keep his book within bounds and so was willing to abridge in so drastic a manner is not especially convincing. The first four books of the Pentateuch were each a third or more larger than his work ultimately became. So also were Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Why, then, should he feel it necessary to recount miracles in the form of abridgments of the narratives before him? We have here, accordingly, a difficulty in the way of formulating a reasonable purpose for a Matthaean compiler using Mark as exemplar. Association Of Physical Activity With Miracles Nobjectionable To Matthaean WriterLet us note that the Matthaean acceptances include accounts of miracles which belong to that class of narratives where something else than the spoken word is introduced into the description at the point where the cure is effected. In these narratives, the Savior is described as touching the body of the afflicted one, or seizing him by the hand, or performing some other act in addition to or by way of substitution for the uttered word. The following list exhibits the accounts of this character which, upon the hypothesis of a dependent Matthew, it is necessary to view as having been accepted by the writer of this Gospel, and as having been accepted without any attempt at modification in respect to the point which now interests us. 1. Touching the leper: “And He stretched forth His hand and touched him” —Mt. 8:3 (=Mk. 1:41). Physical act acompanied by spoken word. 2. Simon’s mother-in-law: “And he touched her hand and the fever left her”— Mt. 8:14 (=Mk. 1:31). No spoken word. BSac 82:325 (Jan 1925) p. 108 3. The ruler’s daughter: “And took her by the hand”—Mt. 9:25 (=Mk. 5:41). No spoken word in the Matthaean account. In addition to these three instances where the Matthaean writer, if indeed he was a compiler using Mark, accepted without modification Markan accounts in which the Savior is described as doing a miraculous deed and at the same time performing a physical act, it may be pointed out that there are also three cases where on his own initiative the compiler of the First Gospel describes a miracle accomplished in the same manner. (1) In Mt. 9:27–31, a passage unparalleled in Mark, we have the case of two blind men, whose eyes He touched, associating with the touch a spoken word: “Then touched he their eyes”—Mt. 9:27. (2) In Mt. 14:28–31, we have, in a kind of supplement to the Markan account of the incident where Jesus walks upon the sea, a narrative telling us of Peter’s request that he be permitted to do the same. When Peter falters in his faith and cries out, the Savior is described as rescuing him not by uttering some command but by performing a physical deed. That is we have a physical act presented as in maintenance of the miracle of Peter walking on the sea. “And immediately Jesus stretched forth his hand, and took hold of him”—Mt. 14:31. (3) In Mt. 20:34, we have in the Matthaean treatment of the Cure of blindness at Jericho a description restricted to the physical, despite the fact that in Mark, at 10:52, it is the spoken word unaccompanied by any physical act that is set forth by the writer. We have in Matthew: “And Jesus . . . touched their eyes”—Mt. 20:34. No spoken word. In Mark, we have, in contrast: “Go thy way thy faith hath made thee whole”—Mk. 10:52. No physical act. That the Matthaean author was quite ready to include accounts of miracles wrought in association with some physical act is well evidenced by the three acceptances cited, by the two narratives peculiar to the First Gospel, and by his own substitution of the physical aspect in the narrative concerned with the blindness at Jericho for the Markan recitation of the words of direction. Nor are we to wonder at his willingness in this connection, in view of the fact that no one of the remaining Gospels is without an instance peculiar to itself. I cite the following cases:

There was a general willingness to record miracles wrought in association with a physical act. This creates a presumption in favor of a similar willingness on the part of the writer of the First Gospel. And besides, we have direct testimony to this willingness on his part in the three cases of acceptances from Mark and in the three cases when he acted on his own initiative. The six instances of accounts of miracles wrought in association with a physical act, and so described in the First Gospel, constitute, it is true, no difficulty in the way of the hypothesis of a Matthew derived from Mark. But the willingness of the Matthaean compiler which must be presumed because of the five Markan, three Lukan and one Johannine instances and must be accepted because this presumption is established by the six Matthaean cases, does bar the way when it is attempted to explain, under the assumption that Matthew is a derivative of Mark, why the Matthaean compiler omitted the accounts of The deaf-mute (Mk. 7:31–37) and of The blind man of Bethsaida (Mk. 8:22–26). An explanation based on the references to physical acts has little or no force. The six instances make it clear that material of the kind embodied in these accounts was acceptable to the writer of Matthew. We have now had before us the acceptances of Matthew in connection with the following points. (1) We have learned that these acceptances amount to 92 per cent, of the whole number of incidents narrated in Mark. Nothing indicative of the impossibility of the purpose of the Markan writer, when he is made compiler, has arisen out of this fact. (2) In the case of fourteen or more miracles which a Matthaean compiler must be viewed as having accepted from the Markan narrative, this compiler abridges the text to the point that he presents, on the average, only three-fifths or less of the history before him. This is an embarrassment to the hypothesis that Matthew is a compilation largely based on Mark. (3) With respect to miracles associated with physical acts, a readiness to narrate such miracles without modification must be ascribed to the Matthaean writer, even when he is viewed as compiling from the Markan narrative. The effect of this disclosure is to bar the explanation based on the physical aspect as to why he rejected certain miracles in Mark, when he is made secondary to the author of this Gospel. Let us now pass to the question concerned with the omissions of Markan events that must be attributed to the Matthaean writer when we assume that the First Gospel was derived from the Second. Seven narratives may be enumerated.

Of the 83 incidents narrated in Mark, these 7 are absent from Matthew. That is to say, the First Gospel, if viewed as the derivative document, is also to be regarded as having omitted 7/83 of the total number of topics listed in the table of contents of the parent writing. The omissions thus amount to about 8 per cent, of the total number. It is important to note at this point that the Matthaean compiler must in consequence be viewed as having omitted a substantial proportion of the topics treated in his exemplar. If it is objected that an explanation is available for two of the seven (Nos. 4 and 5)—that is, for the miracles associated with physical acts—the answer may at once be made that this explanation cannot be urged with any force because of the fact that we must view the writer of Matthew, when he is made a compiler, as quite willing to accept accounts of miraces of the class described. We have already examined into this matter. On the other hand, it must be conceded that, in the case of the narrative which recounts the cure of The blind man of Bethsaida (No. 5), we have an account which prolongs the miracle and associates with it an unusual amount of physical activity. Suppose we say, in view of these considerations, that the Matthaean compiler’s purpose in omitting, not seven but six or seven, topics of importance seems more or less unreasonable. Having accepted 92 per cent, of the available topics, why did he reject all, or nearly all, of the remaining ones? The incident of The man with the unclean spirit is a very notable miracle—so much so in fact that its exclusion is a difficulty calling for especial explanation; the narrative of the Tour through near-by places is just the kind of condensed account that is elsewhere repeatedly found in Matthew;9 the matter of the Appointment of the Twelve is of high importance, which would not have decreased in the lapse of time from a primary to a secondary writing; the miracles concerned with The deaf-mute and The blind man of Bethsaida might well seem acceptable since they would have enabled the author to extend his account of the great works of the Savior; the narrative of The widow’s two mites presents material that would hardly have been without its appeal to a writer who was incorporating so much discourse; and finally, the account of The young man who follows might seem a suitable addition to his description of the Betrayal and Arrest. There has now been developed a very considerable total of what may, for the time, be considered difficulty in the way of the hypothesis that, when the author of the First Gospel is made a compiler who is using Mark, his purpose is to be viewed as a possible one. I do not care—not at least at this juncture—to press the difficulty further than to make it clear that it is a very good offset against a similar difficulty that may be urged in opposition to the possibility of a reasonable purpose when the Markan writer is made a compiler with Matthew before him. When, under this hypothesis, the tables of contents of the two Gospels are compared, it will be found that it is necessary to view the compiler of Mark as having omitted a certain number of topics. It will then be seen, when we come to consider the Markan omissions of whole incidents, that whatever difficulty these may cause for the hypothesis of a dependent Mark is largely offset by the fact that the hypothesis of a dependent Matthew is also beset with a similar difficulty. The Present SituationThe situation at this stage of our investigation into the phenomena of parallelism and non-parallelism may be summed up as follows: We have had before us the matter of Matthaean acceptances of whole incidents and have considered these (1) with reference to the number of acceptances, and (2) with reference to the character of the material accepted. Attention has also been given to the omissions of whole incidents by the Matthaean compiler. But, no substantial evidence against a dependent Mark has so far been found. On the other hand, the fact has been developed that the Matthaean writer when viewed as a compiler must also be regarded as one who was disposed in nearly three-fourths of all accepted cases of miracle to abridge his accounts to an average presentation of but three-fifths of the history before him. This fact stands as a serious obstacle in the way of the hypothesis of a dependent Matthew. Moreover, our investigation has shown that a Matthaean compiler must be considered as having omitted a substantial number of whole incidents. This fact will be found, later on, to afford an offset to the difficulty of viewing Mark as a derivative document when we note that the Markan writer must have omitted a number of whole incidents if he compiled from Matthew. So far, then, our inquiry into parallelism and non-parallelism has developed a situation unfavorable to the hypothesis of a dependent Matthew.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1) The Synoptic Problem, Bibliotheca Sacra, October, 1923, (p. 553) to October, 1924 (p. 499). 2) It is, perhaps, necessary to state that “Possibility of Purpose” is to be taken to mean no more than the possibility of purpose as viewed in the light of available evidence, and is not to be understood as determinable to the point that future evidence could not disturb it. 3) Bibliotheca Sacra, April and July, 1922, pp. 131-152 and 321–350, article “The Order of Events in Matthew and Mark.” 4) These rather improbable though not impossible acceptances are the following: Mt. The Sermon on the Mount. . . . . . . . . . . . . .5:1—7:29 Discourse concerning John. . . . . . . . . . . . . .11:7–19 The unbelieving cities. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11:20–24 Words of thanks and words of comfort. . . . .11:25–30 The demand for a sign. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12:38–45 5) For the figures here, I am indebted to my wife, Carlie McClure Springer. 6) As a matter of fact, the percentage is probably to be put somewhat lower. That is, he must have accepted less than 58 per cent of the text before him, because his account must be understood to include additions of his own; so that the 58 per cent, represents what he accepted plus what he added. 7) The remaining cases of miracles recounted by both writers are the following: 8) The full account includes the list of the Twelve; but as these are also enumerated in Matthew, though in a different connection, I reckon the narrative as covered, for the purposes of this table of omissions, by verses 13–15. 9) Mt. 4:23–25; 9:35; 11:1; 12:15–16; 14:34–36; 15:29–31; 19:1–2. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD