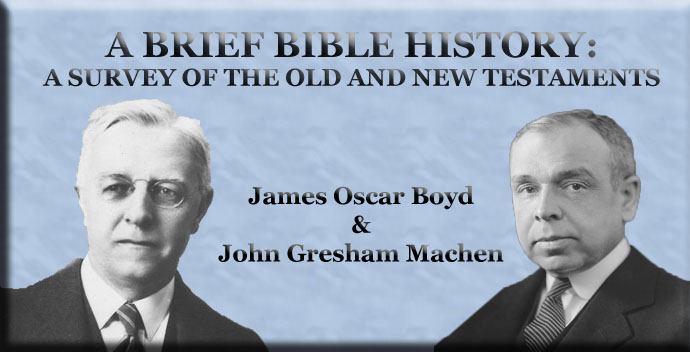

A Brief Bible History:

A Survey of the Old and New Testaments

By James Oscar Boyd & John Gresham Machen

Section I - Lesson VIII

David and Solomon: Psalms and WisdomThe Second Book of Samuel; I Kings, Chapters 1 to 11; I Chronicles, Chapter 10 to II Chronicles, Chapter 9One of SauL's sons, Ish-bosheth, for a short time after the death of his father and brothers in battle, attempted to maintain his right to succeed Saul on the throne. But when Abner, his kinsman and the head of the army, turned to David, son of Jesse, who was already reigning at Hebron as king over Judah, all the tribes followed him. Both Ish-bosheth and Abner soon perished. With his new dignity David promptly acquired a new capital, better suited than Hebron in location and strength to be the nation's center. He captured the fortress of Jebus, five miles north of Bethlehem, his old home, from its Canaanitish defenders, and enlarged, strengthened, and beautified it. Under its ancient name of Jerusalem he made it both the political and the religious capital of Israel. The Ark of the Covenant, which in Eli's time had been captured by the Philistines, had been returned by them, and for many years had rested in a private house, was regarded as the very heart and symbol of the national religion. David therefore brought it first to Jerusalem, and instead of uniting with it its former housing, the old Mosaic tabernacle, he gave it a temporary home in a tent, intending to build a splendid temple when he should have peace. But war continued through the days of David, and at God's direction the erection of a temple, save for certain preparations, was left to Solomon, David's successor. David was victorious in war. His success showed itself in the enlargement of Israel's boundaries, the complete subjection — for the time — of all alien elements in the land, and the alliance with Hiram, king of Tyre, with the great building operations which this alliance made possible. A royal palace formed the center of a court such as other sovereigns maintained, and David's court and even his family were exposed to the same corrupting influences as power, wealth, jealousy, and faction have everywhere introduced. Absalom, his favorite son, ill requited his father's love and trust by organizing a revolt against him. It failed, but not until it had driven the king, now an old man, into temporary exile and had let loose civil war upon the land. Solomon, designated by David to succeed him, did not gain the throne without dispute, but the attempt of Adonijah, another son, to seize the throne failed in spite of powerful support. The forty-year reign of Solomon was the golden age of Hebrew history — the age to which all subsequent times looked back. Rapid growth of commerce, construction, art, and literature reflected the inward condition of peace and the outward ties with other lands of culture. But with art came idolatry; with construction came ostentation and oppression; with commerce came luxury. The splendor of Jerusalem, wherein Solomon "made silver . . . to be as stones, and cedars ... as the sycomore-trees," I Kings 10:27, contained in itself the seeds of dissolution. However, there are two great types of literature which found their characteristic expression in the days of David and Solomon and are always associated with their names — the psalm with David, and the proverb (or, more broadly, "wisdom") with Solomon. Kingdom, temple and palace have long since passed away, but the Psalter and the books of Wisdom are imperishable monuments of the united monarchy. The PsalmsThe Psalter is a collection of one hundred and fifty poems, of various length, meter, and style. As now arranged it is divided into five books, but there is evidence that earlier collections and arrangements preceded the present. Among the earliest productions, judged both by form and by matter, are those psalms which bear the superscription "of David," though it would not be safe to assert that every such psalm came from David's own pen or that none not so labeled is not of Davidic origin. Judged alike from the narrative in the book of Samuel, and from the traditions scattered in other books as early as Amos, ch. 6:5, and as late as Chronicles, I Chron. 15:16 to 16:43; ch. 25, David was both a skilled musician himself and an organizer of music for public worship. It is not surprising, therefore, to find a body of religious poems ascribed to him, which not only evidence his piety and good taste, but also, though individual in tone, are well-adapted to common use at the sanctuary. The psalms are poems. Their poetry is not simply one of substance, but also a poetry of form. Rime, our familiar device, is of course absent, but there is rhythm, although it is not measured in the same strict way as in most of our poetry. The most striking and characteristic mark of Hebrew poetic form is the parallel structure: two companion lines serve together to complete a single thought, as the second either repeats, supplements, emphasizes, illustrates, or contrasts with the first. Proverbs; Job; EcclesiastesPoetry is also a term to which the book of Proverbs and most of the other productions of " Wisdom" are entitled. While they are chiefly didactic (that is, intended for instruction) instead of lyric (emotional self-expression), nevertheless the Wisdom books are almost entirely written in rhythmic parallelism and contain much matter unsuited to ordinary prose expression. In the Revised Version the manner of printing shows to the English reader at a glance what parts are prose and what are poetry (compare, for example, Job, ch. 2 with Job, ch. 3), though it must be admitted that a hard and fast line cannot be drawn between them. Compare Eccl., ch. 7 with Proverbs. "The wise," as a class of public teachers in the nation (see Jer. 18:18), associated their beginnings with King Solomon (Prov. 24:23; 25:1), whose wisdom is testified to in the book of Kings, as well as his speaking of "proverbs," that is, pithy sayings easy to remember and teach, mostly of moral import. I Kings 4:29-34. But the profoundest theme of wisdom was the moral government of God as seen in his works and ways. The mysteries with which all men, to-day as well as in ancient times, must grapple when they seek to harmonize their faith in a just and good God with such undeniable facts as prosperous sinners and suffering saints, led to the writing of such books as Job (the meaning of a good man's adversities) and Ecclesiastes (the vanity of all that mere experience and observation of life afford). In the case of these Wisdom books, as in that of the Psalms, the oldest name — that of the royal founder — is not to be taken as the exclusive author. Solomon, like David, made the beginnings; others collected, edited, developed, and completed. |

|

|

|

QUESTIONS ON LESSON VIII1. In what tribe and town did David first reign as king? How did he secure a new capital when he became king of all Israel? How and why did he make this the religious capital also? 2. What advantages and disadvantages did David's continual wars, and his imitation of other kings' courts, bring to him, his family, and his people? 3. What was David's part in the development of religious poetry? How does Hebrew poetry differ generally from English poetry in form? Name the books of the Old Testament written chiefly or wholly in poetry. 4. Who built the first Temple? Who were "the wise" in Israel, whom did they venerate as their royal patron, and what did they aim to accomplish by their writings?

|

|

-

Site Navigation

Home

Home What's New

What's New Bible

Bible Photos

Photos Hiking

Hiking E-Books

E-Books Genealogy

Genealogy Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Profile

Free Plug-ins You May Need

Get Java

Get Java.png) Get Flash

Get Flash Get 7-Zip

Get 7-Zip Get Acrobat Reader

Get Acrobat Reader Get TheWORD

Get TheWORD