|

The First Punic War (264 to 241 BC) was the first of

three major wars fought between Carthage and the

Roman Republic. For 23 years, the two powers

struggled for supremacy in the western Mediterranean

Sea. Carthage, located in Africa in what is today

Tunisia, was the dominant western mediterranean

power at the beginning of the conflicts. Eventually,

Rome emerged the victor, imposing strict treaty

conditions and heavy financial penalties against

Carthage.

The series of wars between Rome and Carthage were

known to the Romans as the "Punic Wars" because of

the Latin name for the Carthaginians: Punici,

derived from Phoenici, referring to the

Carthaginians' Phoenician ancestry.

Background

In the middle of the 3rd century BC the power of

Rome was growing. Following centuries of internal

rebellions and disturbances, the whole of the

Italian peninsula was tightly secured under Roman

hands. All enemies — such as the Latin league and

the Samnites — had been overcome and the invasion of

Pyrrhus of Epirus had been repelled. Romans had

enormous confidence in their political system and

military power.

Across the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Strait of Sicily,

Carthage was already the dominant naval and

commercial power, controlling most of the

Mediterranean maritime trade routes. Originally a

Phoenician colony, the city, located in Africa in

what is today Tunisia, had become the center of a

wide empire reaching along the North African coast

as well as covering parts of the Iberian

peninsula[citation needed] (now Spain and Portugal)

in Europe. The conflict began after both Rome and

Carthage intervened with an internal power struggle

in Sicily.

Beginning

In 288 BC the Mamertines -- a group of Italian

(Campanian) mercenaries originally hired by

Agathocles of Syracuse from 317 to 289 BCE --

occupied the city of Messana -- modern Messina-- in

the northeastern tip of Sicily, killing all the men

and taking the women as their wives. At the same

time a group Roman troops made up of Campanian

"citizens without the vote" also seized control of

Rhegium, which lies across the straits in Italy. In

270 BCE the Romans regained control of Rhegium and

severly punished the survivors of the revolt. In

Sicily the Mamertines ravaged the countryside and

collided with the expanding regional empire of the

independent city of Syracuse. Hiero II, tyrant of

Syracuse, defeated the Mamertines near Mylae on the

Longanus River and besieged Messina. Following the

defeat at the river Longanus the Mamertines

appealled to both Rome and Carthage for assistance,

and acting first the Carthaginians approached Hiero

to take no further action and convinced the

Mamertines to accept a Carthaginian garrison in

Messana. Either uphappy with the prospect of a

Carthaginian garrison, or convinced that the recent

alliance between Rome and Carthage against Pyrrhus

reflected cordial relations between the two, the

Mamertines petitioned Rome for an alliance, hoping

for more reliable protection. At first, the Romans

did not wish to come to the aid of soldiers who had

unjustly stolen a city from its rightful possessors,

and were still recovering from the insurrection of

Campanian troops at (Rhegium, 271). Most likely

unwilling to see Carthaginian power spread further

over Sicily and get too close to Italy, Rome

responded by entering into an alliance with the

Mamertines. In 264 BC, Roman troops were deployed to

Sicily (the first time a Roman army acted outside

the Italian peninsula). Under the command of Appius

Claudius Caudex two Roman legions were transported

across the straits on pentekonters (ships with 25

oars on each side) and triremes borrowed from allies

in Southern Italy. Following minor skirmishes,

during which Hiero withdrew back to Syracuse, the

Romans sent both consuls and two more legions to

Sicily in the years 263 and 262 BC. The arrival of

these troops influenced many towns to defect to the

Roman side and eventually even Hiero decided to

conclude a peace with the Romans. Under the initial

15 year agreement Syracuse was allowed to stay

independent under the rule of Hiero but was forced

to pay an indemnity of 100 talents (according to the

historian Polybios).Soon enough the only parties in

the dispute were Rome and Carthage and the conflict

evolved into a struggle for the possession of

Sicily.

Land warfare

Sicily is a semi-hilly island, with geographical

obstacles and a terrain where lines of communication

are difficult to maintain. For this reason land

warfare played a secondary role in the First Punic

War. Land operations were mostly confined to small

scale raids and skirmishes between the armies, with

hardly any pitched battles. Sieges and land

blockades were the most common operations for the

regular army. The main targets of blockading were

the important naval ports, since neither of the

belligerent parties was based in Sicily and both

needed a continuous supply of reinforcements and

communication with the mainland.

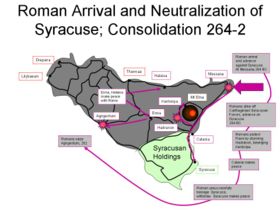

The land war in Sicily began with the Romans landing

at Messana in 264 BC. Despite Carthage's pre-war

naval advantage, the Roman landing was virtually

unopposed. Two legions commanded by Appius Claudius

Caudex disembarked at Messana, where the Mamertines

had expelled the Carthaginian garrison commanded by

Hanno (No relation to Hanno the Great). Rome's

initial strategy was to eliminate Syracuse as an

enemy. From Messana, the Romans marched south,

attacking Hadranon and Kentoripa. These two towns

were on the road around Mt. Etna. Taking these towns

thus protected the right flank of the Roman advance.

The town of Catania immediately made peace with the

Romans. The Romans continued south to Syracuse,

which was briefly besieged. Due to a lack of a

strong Carthaginian response, Syracuse made peace

with the Romans. The towns of Halaisa, located on

the north shore of Sicily, and Enna, located in

central Sicily on the Catania-Agrigentum road and

the Thermae-Gela road, also made peace with the

Romans.

Roman arrival and

neutralization of Syracuse.

With Enna joining the Roman side, the road to the

important coastal city of Agrigentum was open. In

262 BC, Rome besieged the city of Agrigentum, an

operation that involved both consular armies - a

total of four Roman legions - and took several

months to resolve. The garrison of Agrigentum

managed to call for reinforcements and a

Carthaginian relief force commanded by Hanno came to

the rescue and destroyed the Roman supply base at

Erbessus. With the supplies from Syracuse cut, the

Romans found themselves also besieged and

constructed a line of contravallation. After a few

skirmishes, the battle of Agrigentum was fought and

won by Rome, and the city fell.

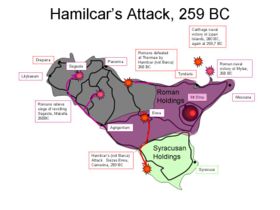

The Roman advance continued westward from Agrigentum

with their forces relieving the besieged cities of

Segeste and Makella in 260 BC. These cities had

sided with the Roman cause, and came under

Carthaginian attack for doing so. In the north, the

Romans, with their northern sea flank secured by

their naval victory at Battle of Mylae, advanced

toward Thermae. They were defeated there by the

Carthaginians under Hamilcar (a popular Carthaginian

name, not to be confused with Hannibal Barca's

father, with the same name) in 260 BC. The

Carthaginians took advantage of this victory by

counterattacking, in 259 BC, and seizing Enna.

Hamilcar continued south to Camarina, in Syracusan

territory, presumably with the intent to convince

the Syracusans to rejoin the Carthaginian side.

Hamilcar's attack.

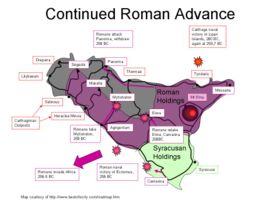

The next year, 258 BC, the Romans were able to

regain the initiative by retaking Enna and Camarina.

In central Sicily, they took the town of

Mytistraton, which they had attacked twice

previously. The Romans also moved in the north by

marching across the northern coast toward Panormus,

but were not able to take the city.

Continued Roman

advance

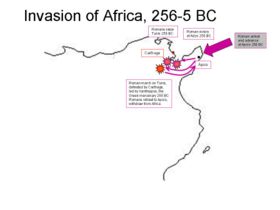

After their conquests in the Agrigentum campaign,

Rome attempted (256/255 BC) the second large scale

land operation of the war. Following several naval

battles, Rome was aiming for a quick end to

hostilities and decided to invade the Carthaginian

colonies of Africa, to force the enemy to accept

terms. A major fleet was built, comprised of

transports for the army and its equipment and

warships for protection. Carthage attempted to

intervene with a fleet of 350 ships (according to

Polybios), but was defeated in the battle of Cape

Ecnomus. As a result, the Roman army, commanded by

Marcus Atilius Regulus, landed in Africa and began

ravaging the Carthaginian countryside. At first

Regulus was victorious, winning the battle of Adys

and forcing Carthage to sue for peace. The terms

were so heavy that negotiations failed and, in

response, the Carthaginians hired Xanthippus, a

Spartan mercenary, to reorganize the army.

Xanthippus managed to cut off the Roman army from

its base by re-establishing Carthaginian naval

supremacy, then defeated and captured Regulus at the

battle of Tunis.

Invasion of Africa.

Roman misfortunes did not end then, however. The

survivors of the African debacle, sailing home, were

caught in a storm, and most of their fleet was

destroyed. The Carthaginians took advantage of this

to attack Agrigentum. They did not believe they

could hold the city, however, so they burned it and

left.

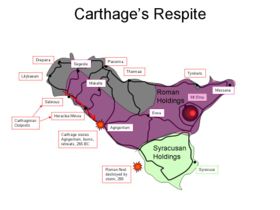

Carthage's respite.

The Romans were able to rally, however, and quickly

resumed the offensive. Attacks began with naval

assaults on Lilybaeum, the center of Carthaginian

power on Sicily, and a raid on Africa. Both efforts

ended in failure. The Romans retreated from

Lilybaeum, and the African force was caught in

another storm and destroyed. The Romans made great

progress in the north. The city of Thermae was

captured in 252 BC, enabling another advance on the

port city of Panormus. The Romans attacked this city

after taking Kephalodon in 251 BC. After fierce

fighting, the Carthaginians were defeated and the

city fell. With Panormus captured, much of western

inland Sicily fell with it. The cities of Ieta,

Solous, Petra, and Tyndaris agreed to peace with the

Romans that same year.

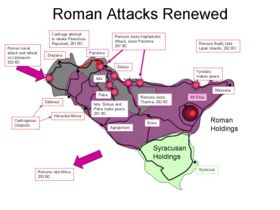

Roman attacks

renewed.

The next year the Romans shifted their attention to

the southwest. They sent a naval expedition toward

Lilybaeum. En route, the Romans seized and burned

the Carthaginian hold-out cities of Selinous and

Heraclea Minoa. This expedition to Lilybaeum was not

successful, but attacking the Carthiginian

headquarters demonstrated Roman resolve to take all

of Sicily. The Roman fleet was defeated by the

Carthaginians at Drepana, forcing the Romans to

continue their attacks from land. Roman forces at

Lilybaeum were relieved, and Eryx, near Drapana, was

seized thus menacing that important city as well.

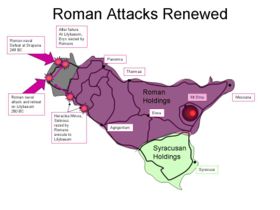

Roman attacks

renewed.

At this point, (249 BC), Carthage sent general

Hamilcar Barca (Hannibal's father) to Sicily. His

landing at Heirkte (near Panormus) drew the Romans

away to defend that port city and resupply point and

gave Drepana some breathing room. Subsequent

guerilla warfare kept the Roman legions pinned down

and preserved Carthage's toehold in Sicily, although

Roman forces which bypassed Hamilcar forced him to

relocate to Eryx, to better defend Drepana.

Nevertheless, Carthaginian success in Sicily was

secondary to the progress of the war at sea; the

stalemate Hamilcar produced in Sicily became

irrelevant following the Roman naval victory at the

battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 BC. As a result

of this naval victory, the Carthaginians sued for

peace and agreed to evacuate Sicily.

Carthaginians

negotiate peace and withdraw.

Naval warfare

Due to the difficulty of operating in Sicily, most

of the First Punic War was fought at sea, including

the most decisive battles. But one reason the war

bogged down into stalemate on the landward side was

because ancient navies were ineffective at

maintaining seaward blockades of enemy ports.

Consequently, Carthage was able to reinforce and

re-supply its besieged strongholds, especially

Lilybaeum, on the western end of Sicily. Both sides

of the conflict had publicly funded fleets. This

fact compromised Carthage and Rome's finances and

eventually decided the course of the war.

At the beginning of the First Punic War, Rome had

virtually no experience in naval warfare, whereas

Carthage had a great deal of experience on the seas

thanks to its centuries of sea-based trade.

Nevertheless, the growing Roman Republic soon

understood the importance of Mediterranean control

in the outcome of the conflict.

The first major Roman fleet was constructed after

the victory of Agrigentum in 261 BC. Some historians

have speculated that since Rome lacked advanced

naval technology the design of the warships was

probably copied verbatim from captured Carthaginian

triremes and quinqueremes or from ships that had

beached on Roman shores due to storms. Other

historians have pointed out that Rome did have

experience with naval technology, as she patrolled

her coasts against piracy. Another possibility is

that Rome received technical assistance from its

seafaring Sicilian ally, Syracuse. Regardless of the

state of their naval technology at the start of the

war, Rome quickly adapted.

Perhaps in order to compensate for the lack of

experience, and to make use of standard land

military tactics on sea, the Romans equipped their

new ships with a special boarding device, the

corvus. Instead of maneuvering to ram, which was the

standard naval tactic at the time, corvus equipped

ships would maneuver alongside the enemy vessel,

deploy the bridge which would attach to the enemy

ship through spikes on the end of the bridge, and

send legionnaires across as boarding parties.

The new weapon's efficiency was first proved in the

battle of Mylae, the first Roman naval victory, and

continued to prove its value in the following years,

especially in the huge Battle of Ecnomus. The

addition of the corvus forced Carthage to review its

military tactics, and since the city had difficulty

in doing so, Rome had the naval advantage. Later, as

Roman experience in naval warfare grew, the corvus

device was abandoned due to its impact on the

navigability of the war vessels. In a single storm

off of Camarina (Sicily) the Romans are said to have

lost all but 80 ships, due perhaps to the

instability caused by the corvus. According to

Polybius the fleet comprised 364 ships while the

historian Eutropius states that there were 464.

Under these assumptions it could be true that

upwards of 100,000 Romans were killed in the

disaster, making it the greatest maritime disaster

in history, and a possible reason why the Romans

abandoned the use of the very effective corvus.

Despite the Roman victories at sea, the Roman

Republic lost countless ships and crews during the

war, due to both storms and battles. On at least two

occasions (255 and 253 BC) whole fleets were

destroyed in bad weather; the disaster off Camarina

in 255 BC counted two hundred seventy ships and over

one hundred thousand men lost, the greatest single

loss in history.[1] One theory for the problem is

the weight of the corvus on the prows of the ships

made the ships unstable and caused them to sink in

bad weather. Following the conclusive naval victory

off of Drepana in 249 BC Carthage ruled the seas, as

Rome was unwilling to finance the construction of

yet another expensive fleet. Nevertheless the

Carthaginian faction that opposed the conflict, led

by the land-owning aristocrat Hanno the Great,

gained power and in 244, and considering the war to

be over, started the demobilization of the fleet,

giving the Romans a chance to again attain naval

superiority. However, during this period, Hamilcar

Barca orchestrated a number of coastal raids in

Italy. Perhaps in response, Rome did build another

fleet paid for with donations from wealthy citizens

and the First Punic War was decided in the naval

battle of the Aegates Islands (March 10, 241 BC),

where the new Roman fleet under consul Gaius

Lutatius Catulus was victorious over an undermanned

and hastily built Carthaginian fleet. Carthage lost

most of its fleet and was economically incapable of

funding another, or to find manpower for the crews.

Without naval support, Hamilcar Barca was cut off

from Carthage and forced to negotiate peace. It

should be noted that Hamilcar Barca had a

subordinate named Gesco conduct the negotiations

with Lutatius, in order to create the impression

that he had not really been defeated.

Aftermath

Rome won the First Punic War after 23 years of

conflict and in the end became the dominant naval

power of the Mediterranean. In the aftermath of the

war, both states were financially and

demographically exhausted. Corsica, Sardinia and

Africa remained Carthaginian, but they had to pay a

high war indemnity. Rome's victory was greatly

influenced by its persistence. Moreover, the Roman

Republic's ability to attract private investments in

the war effort to fund ships and crews, was one of

the deciding factors of the war, particularly when

contrasted with the Carthaginian nobility's apparent

unwillingness to risk their fortunes for the common

good.[citation needed]

Casualties

The exact number of casualties on each side is

always difficult to determine, due to bias in the

historical sources, normally directed to enhance

Rome's value.

According to sources (excluding land warfare

casualties):

- Rome lost 700 ships (to bad weather and

unfortunate tactical dispositions before battle)

and at least part of their crews.

- Carthage lost 500 ships (to the new boarding

tactics and later to the increasingly superior

training, quantity and armarment of the Roman

navy) and at least part of their crews.

Although uncertain, the casualties were heavy for

both sides. Polybius commented that the war was, at

the time, the most destructive in terms of

casualties in the history of warfare, including the

battles of Alexander the Great. Analyzing the data

from the Roman census of the 3rd century BC, Adrian

Goldsworthy noted that during the conflict Rome lost

about 50,000 citizens. This excludes auxiliary

troops and every other man in the army without

citizen status, who would be outside the head count.

Peace terms

The terms of the Treaty of Lutatius designed by the

Romans were particularly heavy for Carthage which

had lost bargaining power following it's defeat at

the Aegates islands. Both sides agreed upon:

- Carthage evacuates Sicily.

- Carthage returns their prisoners of war

without ransom, while paying heavy ransom on

their own

- Carthage refrains from attacking

Syracuse and her allies

- Carthage transfers a group of small

islands north of Sicily to Rome

- Carthage evacuates all of the small

islands between Sicily and Africa

- Carthage pays a 2,200 talent indemnity

in ten annual installments, plus an

additional indemnity of 1,000 talents

immediately [2]

Further clauses determined that the allies of each

side would not be attacked by the other, no attacks

were to be made by either side upon the other's

allies and both sides were prohibited from

recruiting soldiers within the territory of the

other. This denied the Carthaginians access to any

mercenary manpower from Italy and most of Sicily,

although this later clause was temporarily abolished

during the Mercenary War.

Political results

In the aftermath of the war, Carthage had virtually

no state funds. Hanno the Great tried to induce the

disbanded military armies to accept diminished

payment, but kindled a movement that lead to an

internal conflict, the Mercenary War. After a hard

struggle the combined efforts of Hamilcar Barca,

Hanno the Great and others the Punic forces were

finally able to annihilate the mercenaries and the

insurgents. However, during this conflict, Rome took

advantage of the opportunity to strip Carthage of

Corsica and Sardinia as well.

Perhaps the most immediate political result of the

First Punic War was the downfall of Carthage's naval

power. Conditions signed in the peace treaty were

intended to compromise Carthage's economic situation

and prevent the city's recovery. The indemnity

demanded by the Romans caused strain on the city's

finances and forced Carthage to look to other areas

of influence for the money to pay Rome.

As for Rome, the end of the First Punic War marked

the start of the expansion beyond the Italian

Peninsula. Sicily became the first Roman province

(Sicilia) governed by a former praetor, instead of

an ally. Sicily would become very important to Rome

as a source of grain. Importantly, Syracuse was

granted nominal independent ally status for the

lifetime of Hiero II, and was not incorporated into

the Roman province of Sicily until after it was

sacked by Marcus Claudius Marcellus during the

Second Punic War.

Notable leaders

- Ad Herbal, Carthaginian leading

admiral

- Appius Claudius Caudex, Roman consul

- Aulus Atilius Calatinus, Roman

dictator

- Gaius Duilius, Roman consul

- Gaius Lutatius Catulus, Roman consul

- Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina, Roman

consul

- Hamilcar Barca, Carthaginian leading

general

- Hannibal Gisco, Carthaginian general

- Hanno the Great, Carthaginian

leading politician.

- Hasdrubal, Carthaginian general

- Hiero II, tyrant of Syracuse

- Lucius Caecilius Metellus, Roman

consul

- Marcus Atilius Regulus, Roman consul

- Publius Claudius Pulcher, Roman

consul

- Xanthippus, mercenary in the service

of Carthage

- Hannibal the Rhodian, Carthaginian

privateer

Chronology

- 264 BC - The Mamertines seek

assistance from Rome to replace

Carthage's protection against the

attacks of Hiero II of Syracuse.

- 263 BC - Hiero II is defeated by

consul Manius Valerius Messalla and

is forced to change allegiance to

Rome, which recognizes his position

as King of Syracuse and the

surrounding territory.

- 262 BC - Roman intervention in

Sicily. The city of Agrigentum,

occupied by Carthage, is besieged.

- 261 BC - Battle of Agrigentum,

which results in a Roman victory and

capture of the city. Rome decides to

build a fleet to threaten

Carthaginian domination in the sea.

- 260 BC - First naval encounter

(battle of the Lipari Islands) is a

disaster to Rome, but soon

afterwards, Gaius Duilius wins the

battle of Mylae with the help of the

corvus engine.

- 259 BC - The land fighting is

extended to Sardinia and Corsica.

- 258 BC - Naval battle of Sulci:

Roman victory.

- 257 BC - Naval battle of

Tyndaris: Roman victory.

- 256 BC - Rome attempts to invade

Africa and Carthage attempts to

intersect the transport fleet. The

resulting battle of Cape Ecnomus is

a major victory for Rome, who lands

in Africa and advances on Carthage.

The battle of Adys is the first

Roman success in African soil and

Carthage sues for peace.

Negotiations fail to reach agreement

and the war continues.

- 255 BC - The Carthaginians

employ a Spartan general,

Xanthippus, to organize their

defenses and defeat the Romans at

the battle of Tunis. The Roman

survivors are evacuated by a fleet

to be destroyed soon afterwards, on

their way back to Sicily.

- 254 BC - A new fleet of 140

Roman ships is constructed to

substitute the one lost in the storm

and a new army is levied. The Romans

win a victory at Panormus, in

Sicily, but fail to make any further

progress in the war. Five Greek

cities in Sicily defect from

Carthage to Rome.

- 253 BC - The Romans then pursued

a policy of raiding the African

coast east of Carthage. After an

unsuccessful year the fleet head for

home. During the return to Italy the

Romans are again caught in a storm

and lose 150 ships.

- 251 BC - The Romans again win at

Panormus over the Carthaginians, led

by Hasdrubal. As a result of the

recent losses, Carthage endeavors to

strengthen its garrisons in Sicily

and recapture Agrigentum. Romans

begin siege of Lilybaeum.

- 249 BC - Rome loses almost a

whole fleet in the battle of

Drepana. In the same year Hamilcar

Barca accomplishes successful raids

in Sicily and yet another storm

destroys the remainder of the Roman

ships. Aulus Atilius Calatinus is

appointed dictator and sent to

Sicily.

- 248 BC - Beginning of a period

of low intensity fighting in Sicily,

without naval battles. This lull

would last until 241 BC.

- 244 BC - With little to no naval

engagements, Hanno the Great of

Carthage advocates demobilization of

large parts of the Carthaginian navy

to save money. Carthage does so.

- 242 BC - Rome constructs another

major battle fleet.

- 241 BC - On March 10 takes place

the Battle of the Aegates Islands,

with a decisive Roman victory.

Carthage negotiates peace terms and

the First Punic War ends.

Bibliography

- The Punic Wars, by Adrian

Goldsworthy, Cassel

- The First Punic War, A

military history by J.F.

Lazenby, 1996, UCLPress

- World History by Polybius,

1.7 - 1.60

- Evolution of Weapons and

Warfare by Trevor N. Dupuy.

Footnotes

1 Trevor N. Dupuy, Evolution of Weapons and Warfare

2 Polybius, 1:62.7-63.3 |