| Muwattalli II King of the Hittites 1306-1282 BC | |

|

He was the Son of Muršili II

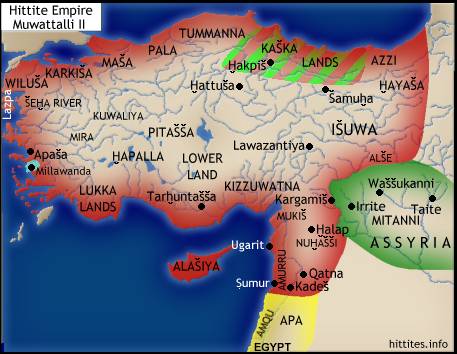

(Contemporary with Adad-nirari I of Assyria (See Peter Machinist (1987)) Muwattalli appears to have ascended to his father's throne in good order. Unfortunately, very few records exist from this reign. Peace in the West In the far northwest, on the coasts of the Aegean and Marmara seas, the kingdom of Wiluša continued to be ruled by Alakšandu. The other Arzawa lands passed under Muwattalli's control with equally little fanfare. Manapa-Tarhunta continued to rule in Šeha River Land, just to the south of Wiluša. Kupanta-Kurunta ruled on as king in Mira and Kuwaliya, as indeed he would through the entirety of Muwattalli's reign. A man named Ura-Hattuša was also king now, presumably in Hapalla, although the name of his kingdom is broken away in the document that mentions him. All in all, the west seems to have remained firmly in Hittite hands at Muwattalli's accession. One possible exception to this is the kingdom of Millawanda. Its abscence boded ill for the empire, on account of what it seems to imply. Millawanda would soon show up in opposition to Hittite interests as the kingdom of Ahhiyawa once again attempted to establish its interests in western Anatolia, and it may be that Millawanda had already slipped away from the Hittites upon Muwattalli's accession. Prince Hattušili and the North The career of Muwattalli's brother Hattušili, the priest of Šaušga, took a new direction during this king's reign. Muwattalli placed his brother in charge of military expeditions, few of which we actually know about. But Hattušili has told us about his “first manly deed”, which was a campaign to the north of the capital - a region with which his life had become and would remain intimately bound. The incessant campaigning of Muršili II had failed to pacify the Kaškans, and now they devastated the lands of Šadduppa and Dankuwa. Muwattalli installed Hattušili in the city of Pitteyarika, located upstream from the city of Šamuha, but did not give him enough infantry and chariotry to satisfy him. Nevertheless, Hattušili marched forth against the enemy, trapped them in the vicinity of Hahha, defeated them, and set up a victory stela. He reconfirmed the liberated Hittites in their former lands, and he seized the enemy leaders and allotted them to his brother, Muwattalli. Hattušili finished his account of this campaign by declaring, “On this campaign my lady Šaušga called me by name for the first time.” It was an auspicious beginning. Muwattalli advanced Hattušili to the extremely important position of Chief of the Royal Bodyguard, which essentially made him third in command in the empire. Muwattalli also made him Priest of the Storm God of Nerik, who, unfortunately, still had to be worshipped from the city of Hakpiš. This position apparently made him the governor of the Upper Lands, which at this time included Šamuha and Pitteyarika, Hakpiš, Ištahara, Tarahna, Hattina, and Hanhana. These cities were all located in the region bordering on Kaškan territories, so that Hattušili's position was extremely important to the immediate safety of the capital. But his promotion did not pass untroubled. The former governor of the Upper Lands, an elder relative by the name of Arma-Tarhunta, son of Zida (the brother of Šuppiluliuma I), had been relegated to a subordinate position as the administrator of the Upper Land under Hattušili. Apparently, this reduction in rank did not sit well with him. So he, along with other men, began to speak ill of Hattušili, so that he fell under his brother's suspicion. Muwattalli decided to subject him to the ordeal of the “Divine Wheel”. According to Hattušili, the goddess Šaušga appeared to him in a dream and told him not to fear. Indeed, he passed the ordeal. As a result, Muwattalli once again regularly entrusted imperial troops to Hattušili's command, and - with the favor of Šaušga, of course - Hattušili conquered the enemy lands that he marched against. Trouble in the West While things may have begun well for Muwattalli in the west, such a situation could not be expected to last, and of course it didn't. Muwattalli was extremely suspicious of the Arzawan subjects of Kupanta-Kurunta of Mira and Kuwaliya, and as it turned out his suspicions were justified. Maša and other Arzawan lands rose up against their Hittite overlord and attempted to overrun Wiluša, and Alakšandu of Wiluša sent to Muwattalli for help. With Muwattalli's assistance, these western enemies were defeated. The event called for a new cementing of relations, and Muwattalli drew up a new treaty of vassalage for Alakšandu. In it Muwattalli required Alakšandu to join him if he went on campaign from Karkiša, Maša, Lukka, or Waršiyalla. From this list we can see that Muwattalli still maintained Hittite dominence over the west, stretching from the Lukka lands in the far south up to Wiluša in the far north. This treaty, stemming from the far western end of the empire, incidentally reveals some crucial evidence for the far eastern end of the empire. A part of Alakšandu's military obligations was that, if Muwattalli requested them, he would have to send infantry and chariotry to the Great King's assistance if those kings who were Muwattalli's equals were to wage war against him. Altogether, this included the kings of Egypt, Babylonia, Hanigalbat, and Assyria. Here we find the first signs of Hittite acceptance of great power status for Assyria, and probable evidence that Mitanni (Hanigalbat) had once again attained an independent international status. It was to be the last hurrah for this once mighty empire. New troubles soon afflicted Muwattalli in the west. The kingdom of Ahhiyawa had by no means given up its ambitions there, and they now found an able partisan in a warrior named Piyama-radu. Where this man originated is not clear, but his grandfather appears to have been based on the island of Lazba, which is better known today by its Greek name; Lesbos. Lazba was part of the domain of Manapa-Tarhunta of Šeha River Land. The Ahhiyawans could not seduce Manapa-Tarhunta away from the Hittites, but they seem to have had better luck with Wiluša. The Hittite king sent troops to Šeha River Land, and from there they attacked Wiluša. Manapa-Tarhunta seems to have excused himself from these activities by claiming that he was overcome by serious illness. It may very well have been true, since Manapa-Tarhunta disappears from the historical record after this point. Manapa-Tarhunta was himself having problems with the Ahhiyawans. They controlled Millawanda, which was under the rule of a man named Atpa. Atpa was, or would soon become, the son-in-law of Piyama-radu. But he himself was in a greater position than Piyama-radu, who seemed to be a man in constant search of a kingdom. Perhaps playing upon Manapa-Tarhunta's febrility, he attacked Lazba in hopes of wresting it from his control. As well as waging open war on the island, Piyama-radu's grandfather began undermining the Lazbans' loyalty. Both Manapa-Tarhunta and the Hittite Great King himself had a class of men known as ṢARIPU-men living on the island. These men owed tribute to their respective rulers. Piyama-radu's grandfather played upon this unwelcome burden in order to incite a revolt on the island. It worked, and all of Manapa-Tarhunta's and the Great King's ṢARIPU-men went over to the enemy. A series of antagonistic letters between Piyama-radu and the Hittites ensued which involved a Hittite official named Kaššu, and Manapa-Tarhunta himself wrote a letter to the Hittite king in which he outlined the history of the dispute and how his illness had incapacitated him. The ultimate resolution, unfortunately, is not known. But Piyama-radu would continue to trouble the Hittites, under Atpa's and the Ahhiyawan's auspices, and Wiluša would remain a point of dispute between Hatti and Ahhiyawa for some time to come. Manapa-Tarhunta, perhaps as a result of his illness, did not survive Muwattalli's reign. When he finallly passed on, Muwattalli installed a man named Mašturi - presumably one of Manapa-Tarhunta's sons - on the Šeha River Land throne and further gave him his sister, Maššanauzzi, to be his wife and the queen of the kingdom. Trouble in the East At an unknown point of time, Šattiwaza, the king of Mitanni installed by Šuppiluliuma I, had been replaced by a man named Šattuara. Now independent of Hittite rule, Mitanni began a precipitous slide towards Assryian annexation. Adad-nirari I (1305-1274), son of Arik-den-ili, finally brought low this once mighty land. This miltaristic ruler of Assyria sought to revive the flagging fortunes of the Assyrian kingdom, and he proved quite adept at it. Adad-nirari claimed that it was Šattuara who attacked him. So, at the command of his god Aššur, Adad-nirari went forth, captured him, and brought him back to Aššur. Having made him take an oath of vassalage, he then released him back into his land. Mitanni, known to the Assyrians as Hanigalbat, had been forced into the Assyrian camp. Šattuara remained loyal to Adad-nirari for what remained of his life. We do not know how much longer Šattuara lived, so we can only poorly judge the gap between his subjugation and the accession of his son, Wasašatta. Wasašatta, who definitely ruled from the city of Taite rather than from the old capital Waššukkanni, was not interested in continuing to subject himself to Assyrian rule, and so he rebelled against Adad-nirari and sought out Hittite assistance. It was a poorly made decision. The Hittites accepted the gifts he gave them for their assistance, but never actually came to his aid. Adad-nirari marched against him and captured Taite. But he didn't content himself with that. He further captured the cities of Amasakku, Kahat, Šuru, Nabula, Hurru, Šuduhu, and even Waššukkanni. He looted Wasašatta's palace and carried off the treasures amassed by his anscestors to Aššur. Wasašatta himself, however, had not yet yielded. He retreated before the Assyrian king to the city of Irrite. It availed him nothing. Adad-nirari not only captured this city, he utterly destroyed it.

Wasašatta would not be re-instated as a vassal ruler. Mitanni no longer even enjoyed the status of a vassal kingdom within the Assyrian empire. It was wholly annexed to Assyria. The capital Taite fared much better than Irrite. Adad-nirari restored its irrigation system, built a palace there, and erected his inscribed steles in the city. Adad-nirari used his great victory over this once mighty empire in order to continue to seek international recognition of his importance, and as a means of intimidation. Now that he directly faced the Hittites across the Euphrates, he took a decidedly more aggressive stance towards them than his ancestors had. For his part Muwattalli, while forced to recognize his power, felt no need to seek his friendship,

In spite of his belicose attitude, this very same letter seems to have concluded with information about the dispatch of a Hittite messenger, so that relations, while obviously not particularly warm, were not entirely severed. Undoubtedly the trade relations which had probably always been important for these two lands prevented a complete break between them. It is more than a little possible that Muwattalli was also concerned about his ability to protect his valuable Syrian possessions from this distressingly successful Assyrian king. A New Capital The foreign scene was not the only arena of great changes. There was an internal change of profound significance as well, which would ring down beyond the end of the empire. With the support of a favorable omen by Muwattalli's patron deity, the Storm God of Lightning, the Great King gathered up the idols of the Hittite gods and of the deceased kings and took up Tarhuntašša (“Belonging to Tarhunta”), a southern city located in the Lower Land, as his capital. The old capital city was placed under the authority of Mittanna-muwa, the man who had earlier saved the life of Muwattalli's younger brother Hattušili. In his place as the Chief of the Scribes Muwattalli promoted Burandaya, one of Mittanna-muwa's sons. How the king's subjects viewed this break with tradition is not well recorded, but clearly there was opposition. In later years Hattušili, who otherwise portrays himself as a staunch partisan of his brother, could only try to distance himself from that decision in a prayer to the Sun Goddess of Arinna;

Many scholars have speculated on why Muwattalli wanted to leave the capital city in favor of a new residence, but the man himself has left us no documents revealing his thoughts. We are simply left with the unsatisfactory statement that the move was due to a favorable omen. We are further hampered by the fact that the archaeological site of Tarhuntašša, which to this day presumably protects Muwattalli's archives, has not been located, and cannot even be firmly placed. Somewhere either in the Gok Su valley or in the vicinity of Kayseri is about as close as we can come to specifying its location. The shift of capital resulted in chaos in the north. Freed from the immenent presence of the Great King, there was widespread unrest in the Kaškan lands. At this time Pišhuru was apparently still the most formidible of the Kaškan lands. Also joining in the revolt were the sometimes-Hittite lands of Išhupitta and Daištipašša. Together, these three lands were able to take away from the Hittites the land Landa, the land Marišta, and some fortified towns. The Hittites failed to stem the tide, and the Kaškans continued to sweep southward, crossing the Maraššanda River and attacking the land Kaniš. Similarly, the cities of Ha[...], Kuruštama, and Gazziura rebelled and set about attacking the unfortified Hittite towns in the vicinity. The land Durmitta also became hostile and attacked the land Tuhuppiya. Finding nothing to stop them in the land Ippaššanama, they kept going and attacked the land Šuwatara. Only the cities of [...]ša and Ištahara escaped the Kaškan ravages. Clearly, something drastic had to be done to stabilize the situation. Territory which had once been part of the core of the empire had now fallen into enemy hands. The frontier had moved considerably to the south of where it had once been. The solution devised by Muwattalli would have serious consequences for the future of the empire. He called on the assistance of his brother Hattušili, who had had such success in the northern lands previously. Muwattalli gave Hattušili a resource base for his reconquests that the Great King would not have to try to maintain from his distant capital. This resource base was a newly created vassal kingdom for his brother consisting of that portion of the northern lands that were still loyal to the Hittites. Even here the imperial court was not completely absent from at least the initial expenses of establishing the defense of the new kingdom, in that Muwattalli came and fortified the towns of Anziliya and Tapikka. But the Great King ended his involvement there, refusing to go out and campaign against Durmitta and Kuruštama himself. Instead, he gathered together the imperial troops and led them back to Tarhuntašša. Hattušili was henceforth left to rely on his own resources. Hattušili's reward for undertaking this monumental task would be rich indeed. Muwattalli granted those lands which had been lost to the Kaškans to his brother. Hattušili, who refered to these districts as “empty” lands, would be able to govern them on the condition that he could first reconquer them. Thus, beginning with a small kingdom, Hattušili could potentially make himself into one of the most powerful figures in the empire.

His vassal kingdom was known as Hakpiš, after its capital. This was the city in which the exiled cult of the Storm God of Nerik still dutifuly carried out its responsibilities, a fact which would later be of great significance. As for his hypothetical territory, it unexpectedly includes a large number of territories to the northwest of the capital, which indicates that the trouble was much more widespread than Hattušili otherwise indicates. Of particular interest in this respect is the known troubles that Muwattalli was having in the kingdom of Wiluša. Could those disturbences have spread much further east than would otherwise be suspected? The nature of Hattušili's authority is of great interest in itself. Here Hattušili was given command of a vast expanse of territory and, particularly in the form of the kingdom of Hakpiš, he was given a great deal of autonomy as well. But along with these great rewards came great risks. The Hittites were not in control of most of these territories. At the time of the grant, Hattušili was placed in charge of what was largely a “paper” territory. He could very easily have died in his efforts to make his authority real. This type of arrangement, consisting of grants of large tracts of land and great autonomy offset by great danger, is known from other historical periods as being common in frontier districts. This sort of potential reward was the best way to entice adventurous men to risk life and limb in a difficult and unpredictable situation. It takes a certain personality to succeed in such a situation. There were certainly more secure sources of income and profit in lands further in from the frontier, but these lands would certainly have been much smaller, with much less potential profit and much less freedom of action than what could be gained from the successful conquest of vast frontier lands. Hattušili was bold enough, and situated in exactly the right spot at the right time, to seize the opportunity presented to him. Once he was made responsible for these territories, he set about energetically reclaiming them for the empire. But the fragmented nature of authority in the Kaškan lands made a grand reconquest of the lost districts virtually impossible, and so Hattušili resorted to building his authority by a combination of force and diplomacy, so that,

He would be occupied with this task for ten years. The influence that these frontier days would have on his ideas of governance would be evident in his later career, when he adroitly mixed violence - or at least the threat of it - with diplomacy. The turning point in his northern campaigns appears to have come in a decisive battle against the Pišhurun Kaškans at or near the city Wištawanda. The Pišhuruns had managed to push their borders as far as Taggašta on the one side and Talmaliya on the other. The cities of Karahna and Marišta had fallen under its domination. The Pišhurun leader led a force of 800 chariots and countless infantry. At Muwattalli's command, Hattušili marched against the Pišhuruns, although Muwattalli had only given him 120 chariots and no infantry whatsoever. Nevertheless, “Šaušga, my lady, ran before me then, and at that time I conquered the enemy by means of my own body. When I killed the man who was (their) leader, the enemy fled.” This resounding victory resulted in a widespread counter rebellion in the captured Hittite towns, who rose up and began to expel their Kaškan occupiers. To commemorate this important victory, Hattušili set up a victory stela in Wištawanda. Having secured the northern lands for the Hittite empire, Hattušili was thus able to call upon a significant armed force to bring to his brother's aid when Muwattalli set forth on his epic campaign against the Egyptians. The Battle of Kadesh The Battle of Kadesh, which took place in the 5th year of the reign of Rameses II of Egypt, is known almost exclusively from the Egyptian point of view. It was the culmination of a follow-up campaign conducted by Rameses in the previous year, at which time he had marched north and captured territory as far north as Beruta and Amurru. Bentišina of Amurru sent a letter to the Hittite king formally declaring his forced conversion to the Egyptian cause. This loss of Amurru would lead to what is today the most famous battle of the ancient Near Eastern world - the battle at the city of Kadesh on the Orontes River. The recovery of Amurru and the capture of its traitorous king were the main objectives of the Hittite campaign, as stated in a prayer made by Muwattalli before he left on campaign,

In order to accomplish this task, he brought to Syria what may have been the greatest force ever assembled by a Hittite king for a single battle, a force estimated to consist of about 47,500 troops. Facing off against the the Hittite threat, Rameses is believed to have brought about 41,000 troops with him. For this battle, Muwattalli implemented a recent innovation in chariot warfare. Whereas traditionally each chariot contained two men, some of Muwattalli's chariots now carried three men acting in concert. This is an interesting and important innovation in chariot warfare, for the three-man chariot would come to outlast the Hittite empire itself. Further, the evidence would seem to indicate that it was a chariot capable of carrying three men that found its way eastward to China. It is unfortunate that we do not know whether the Hittites invented this new chariot themselves, or whether they adopted it from one of their neighbors. Something else this new innovation, which supplemented but did not replace the two-man chariot, seems to indicate is specialization in chariot construction and battle tactics. We do not have any ancient Near Eastern documents which might reveal specialized roles for different chariot types, or indeed any document outlining the principles of chariot warfare at all. But if we turn our attentions eastward to China, which adopted chariot warfare from the west, we have several documents on the topic of warfare written during the age of Chinese chariot warfare. In this light, it might be helpful to consider the words of the most famous military philosopher of all, Sun Tzu, who stated in The Art of War, “If there are one thousand four-horse attack chariots, one thousand leather-armored support chariots, one hundred thousand mailed troops... (various other factors culminating in the daily expense of an army)” Clearly, in China there were various types of chariots used contemporaneously. It would now seem that this sort of specialization had already begun at least as early as the early 13th century B.C. In addition to the large numbers of troops involved, that the Battle of Kadesh was a major campaign for the Hittites is also clear from the wide array of locales that the Great King summoned his forces from. They came from every corner of the empire. According to the Egyptian recounting of the battle, the Hittite contingents came from Mitanni, Arzawa, Dardany (in Cilicia?), Maša, Pitašša, Arawanna, Karkiša, Lukka, Kizzuwatna, Kargamiš, Ugarit, Halap, Nuhašši, Kadesh, and a place called, by the Egyptians, Mwš3nt. We have already indicated that other troops, such as those that Hattušili brought with him from the north, also joined the campaign. At the opening of the campaign season, the Egyptian army marched north along the Palestinian coast. Upon entering southern Syria, Rameses detached a force from his army, presumably to secure the port of Ṣumur, after which it was to rejoin the main army at Kadesh. In the meantime, the main body of the Egyptian army turned inland and marched towards Kadesh. The Egyptian army consisted of four divisions, each named after an Egyptian god; Amun, Re (Pre), Ptah, and Suteh (Seth). They approached the Orontes river from the east at a ford called Šabtuna approximately eight miles south of Kadesh. To the south of this town the Egyptians encountered two “Shosu of the tribes of Shosu” who claimed that they were there as messengers from their tribes, which were willing to abandon the Hittite cause in favor of the Egyptian. Rameses asked them where their tribes were, and they replied,

In fact, the two Shosu men were actually Hittite scouts, and far from cowering far to the north in Halap, Muwattalli had actually encamped and made ready his entire army on the northeast side of Kadesh, behind “Old Kadesh”. Rameses then demonstrated the importance of scouting out enemy territory by failing to do enough of his own. Completely oblivious to the presence of an enormous Hittite army which “covered the mountains and valleys and were like locusts in their multitude”, he took the division of Amon, crossed the Orontes, and hurried on to encamp to the northwest of Kadesh. Only then did the Egyptians capture two more Hittite scouts and beat the truth out of them. It was these scouts who confessed the true position of the Hittite army. Denied the initiative, now Rameses could only react to the threat. He summoned his commanders into his presence and preached to them the virtues of proper scouting. The commanders could only confess their sin before their august sovreign. After the lecture, the vizier was dispatched to hasten on the rest of the Egyptian army to the Pharaoh's rescue. The Pharaoh's family was hastened out of harm's way by prince Pre-hir-wonmef. But even while Rameses was lecturing his commanders, the battle was engaged. The second Egyptian division, that of Re, was still in the process of crossing the Orontes back at the Shabtuna ford. They were completely unprepared for battle as 2,500 Hittite chariots fell upon them. Their discipline collapsed, and far from hurrying to the Pharaoh's assistance, they simply fled willy-nilly into his camp. The Hittite army swept on across the river and fell upon the Pharaoh's camp and the division of Amon. This division collapsed too, leaving the Pharaoh to defend himself with only a small force (whom he didn't give any credit to later). The Hittites entered the Egyptians' camp and surrounded the Pharaoh. Rameses, now facing a desperate fight for his life, summoned up his courage, called upon his god Amun, and fought valiantly to save himself. Fortunately, at this time Rameses received some very opportune assistance. The force from Amurru arrived and lent their strength to the Pharaoh's cause. They attacked the rear of the Hittite chariotry and staved off a total defeat. Muwattalli responded by sending in a thousand more chariots, but after six charges they found themselves driven back to, and into, the Orontes. Even the King of Halap had to be dragged from the river. The Egyptians later gleefully depicted him being held upside down in order to empty the water out of him. The Egyptian chariots could not pursue the Hittites across the river, and as the day was ending, the battle was disengaged. The vizier finally showed up with the division of Ptah at the end of the day. They had little to do but round up prisoners, collect booty, and count the enemy slain by means of severing off the right hands of the dead. The scattered Egyptian forces began returning to the camp, where they supposedly praised Rameses' valiant stand. The arrival of the division of Suteh completed what remained of the Pharaoh's army. Rameses himself took the time to berate his returning troops for their cowardice. The next morning Rameses rose and prepared to resume the fight. Battle was once again engaged, but does not seem to have been noteworthy either way. It was no matter. Muwattalli's surprise attack had not secured a rapid victory, and apparantly the Great King wasn't interested in an extended engagement. Rameses claimed that Muwattalli wrote to the Pharaoh and sued for peace. The Hittite army had failed to gain a victory in the face of what earlier must have seemed certain success, and an entire division of the Egyptian army remained completely unengaged. Muwattalli may have decided that an alternate plan should be pursued. In any event, Rameses had had enough, and he accepted terms and withdrew his army from the field. In fact, he seems to have made a full retreat back to Egypt. The Empire After the Battle of Kadesh Muwattalli may not have wanted to face the Egyptian imperial army again, but he had no compunction about crushing the armies of the local kings and restoring Hittite prominence in Syria. Amurru was forced to submit to Hatti again, and its ruler, Bentišina, was removed from his throne and a man named Šapili was installed in his place. Although the main objective of his campaign had been accomplished, Muwattalli then chose to push on southward into Syrian territory. He successfully marched as far as Apa. After capturing that territory, he ended his campaign and returned to Hatti, taking Bentišina with him. He chose to leave his brother Hattušili in Apa. We do not know how long Hattušili remained in Apa, other than to say that he couldn't have stayed more than two years. The reason for Hattušili's departure from Apa remains uncertain. It seems likely that he was forced out. In the seventh year of his reign, Rameses II returned to Syria once again. This time he proved more successful against his Hittite foes. On this campaign he split his army into two forces. One of these forces was led by his son, Amon-hir-hepešef, and it chased warriers of the Šosu tribes across the Negev as far as the Dead Sea, and it captured Edom-Seir. It then marched on to capture Moab. The other force, led by Rameses, attacked Jerusalem and Jericho. He, too, then entered Moab, where he rejoined his son. The reunited army then marched on Hesbon, Damascus, on to Kumidi, and finally recaptured Apa. This would seem like the best time for us to quietly remove Hattušili from Apa and send him back to Hatti. Rameses extended his military successes in his eigth and ninth years. He crossed the Dog River (Nahr el-Kelb) and pushed north into Amurru. His armies managed to march as far north as Dapur, where he erected a statue of himself. The Egyptian pharaoh thus found himself in northern Amurru, well past Kadesh, in a city which Egypt had not controlled for over one hundred and twenty years. His victory was ephemerel though. A thin strip of territory pinched between Amurru and Kadesh did not make for a stable possession. Within a year, they had returned to the Hittite fold, so that Rameses had to march against Dapur once more in his tenth year. This time he claimed to have fought the battle without even bothering to put on his corslet until two hours after the battle began. His second success here was as meaningless as his first. Thirteen years later, when he finally called it quits and made peace with the Hittites, he would recognize Hittite control of this region. While Egypt struggled to revive its flagging reputation in Syria, back in Hatti the saga of Hattušili's career continued to unfold. Whenever it was that Hattušili left Apa, either before or due to Rameses' seventh year campaign, he stopped on his way home at the city of Lawazantiya in order to offer libations to the goddess Šaušga. While there, he married Pudu-Hepa, the daughter of Pentib-šarri, Priest of Lawazantiya. There may have been some question about the appropriateness of this marriage, since on several occasions Hattušili felt obliged to defend this action, most strongly in the following statement made by him,

In spite of a possibly questionable background, this woman would rise to become the most influential Great Queen known in Hittite history, in many ways overshadowing her vigorous husband. After his marriage, Hattušili returned to the northern reaches of the empire and set about trying to stabilize his domain. To this end he fortified the towns of Hawarkina and Dilmuna. But now Hakpiš itself rose up against him. Without the aid of imperial troops, Hattušili called upon his Kaškan allies in order to suppress the rebellion himself. He used his victory as an opportunity to confirm himself as king of Hakpiš and Pudu-Hepa as its queen. His vassal kingdom seems to have included the cities of [...]ta, Durmitta, Ziplanda, Hattena, Hakpiš, and Ištahara, which Hattušili repopulated with Hittite subjects. He further claims to have been in charge of Hattuša itself. Hattušili had now become a semi-independent power within the empire, and dutifully made Šaušga into his kingdom's patron deity. Hattušili requested that Muwattalli give him Bentišina, the deposed ruler of Amurru. Muwattalli did so, and Hattušili brought him to Hakpiš where he was given a household of his own. This relationship would later enable the disgraced house of Bentišina to rise up from its humiliation.

Let us take a moment to reflect on Muwattalli's reorganization of the north. It was perhaps one of the most disastrous precedents ever set by a Great King. Vassal kingdoms were organized upon the treaty system. The treaty system had a long and distinguished history, stretching back to the time of Telipinu. As has been explored, it was initially used as a means of establishing peace between equal powers. This system was modified first by Tudhaliya II and then more extensively by Šuppiluliuma I to include subordinate kingdoms as a means of organizing distant foreign conquests. But throughout its history, the treaty system had consisted of two parties; one Hittite and the other foreign. The internal organization of Hatti remained a provincial system, with the governors receiving instructions from the Great King on how to perform their duties. As well as staying informed of crop conditions, the Great King also had to be informed of troop movements within the provinces, and he had the power to approve, disapprove, or redistribute these troops. These were imperial troops, at the beck and call of the Great King himself. Further, there were no set authorities in charge of military campaigns. Omens were often taken in order to determine who, among a pool of candidates, would lead the troops on a particular campaign. This meant that the troops only permanent authority figure was the Great King himself. Their immediate commanders could change from campaign to campaign. Not to mention that the Great King retained control of his commander's military posts. Hattušili's own migratory career is a good example. These two powers were surely a potent means of keeping the armies' loyalties focused on the Great King. It is surely no coincidence that the Great Kings who were overthrown in early Hittite history were usually not overthrown in civil wars, but rather by means of assassination within the royal family. Now Muwattalli was internalizing the treaty system. He took a territory which had been a Hittite province, part of the core of Hatti itself, and turned it into a vassal kingdom. Vassal kingdoms were subordinate to the Great King on a different principle. The extant treaties make it clear that the vassal king was in charge of his kingdom's own army, and it was only his duty to use his army to render aid to the king. Hattušili himself repeatedly emphasizes how little help he received from his brother, and how much he accomplished things by his own means. This meant that now a Hittite army would have a new focus of loyalty - the vassal king. The problem that this created becomes obvious due to the rapidity in which it began to tear apart the empire. Muwattalli may have escaped its consequences, but his son did not. But we must not get ahead of ourselves. Even before his installation as King of Hakpiš, Hattušili's old adversary, Arma-Tarhunta, began once again to scheme against him. Some time after his installation in Hakpiš, Arma-Tarhunta brought an indictment of sorcery against Hattušili. But Hattušili presented his own counter indictment against Arma-Tarhunta, accusing him of filling even Šamuha, Šaušga's cult city, with sorcery. Hattušili emerged victorious. Arma-Tarhunta was convicted of sorcery, and his wife and sons were convicted along with him. The family and their estate were handed over to Hattušili to do with as he wished, with the exception that Muwattalli declared the innocence of Šippa-ziti, one of Arma-Tarhunta's sons. Because Arma-Tarhunta was one of Hattušili's relatives, and an old man as well, he took pity on him and took only half of his estate and banished him to the island of Alašiya. The rest of Hattušili's career during the reign of his brother seems to have been uneventful. But there is one other event of importance which, unfortunately, cannot be placed in its proper chronological sequence. At some point, Muwatalli gave over one of his sons, named Kurunta, to Hattušili to raise along with Hattušili's own sons. Kurunta and one of Hattušili's sons, Tudhaliya, supposedly became good friends (see the Bronze Tablet). This son, this Kurunta, would eventually play a pivotal role in the weakening of the Hittite empire. But that still lay in the future. It is another son who must attract our attention for now. An Unhappy Marriage and its Consequences One of the great misfortunes of Muwattalli's reign was his troubled marriage to Tanu-Hepa. Ultimately, the two of them fell into continuous legal wrangling. These disputes would have black consequences for the future of the empire. It was difficult to find someone eminent enough to review their cases, and the unhappy judge selected was Urhi-Teššup, Muwattalli's son by a second-rank wife. He claimed to have wanted no part of the proceedings, feeling that they would bring bad luck to him, but he was not permitted to refuse,

In later years his reluctant participation would nonetheless come back to trouble him. But for the moment he would actually benefit more than he could have perhaps imagined. For the royal children by Tanu-Hepa apparently sided with their mother and her supporters and thereby became implicated against the king. Ultimately, this seems even to have led to their deaths along with those of the queen's other partisans. At the very least, it meant that any sons Muwattalli may have had by the Great Queen were no longer permitted to succeed to the throne. Since Urhi-Teššup apparently found himself judging in his father's favor in these disputes, he undoubtedly earned his father's unending gratitude. Urhi-Teššup, a second-rank son with no hopes of inheriting the throne, now found himself the heir-apparent. Foreign Relations Aleppo: Muwatalli renewed a treaty with Talmi-Šarruma of Halap (witnessed by Šahurunuwa, king of Carchemish, a younger son of Šarri-Kušuh) which his father Muršili II had also made with Talmi-Šarruma. Arzawa: Made up of four lands: Arzawa (king Piyama-Kurunta), Mira-Kuwaliya (king Kupanta-LAMMA, son of Mašuiluwa, king of Mira-Kuwaliya, descended from the kings of Arzawa on his father's side, and the kings of Hatti on his mother's side (his mother was a daughter of Šuppiluliuma I)), Hapalla (king Ura-Hattuša), and Wiluša (king Alakšandu). Had to campaign against it. Did so successfully, maintaining their subjugation. Alakšandu installed in Wiluša. The River Šeha Land was not considered to be part of Arzawa, but it remained under Hittite control. Muwatalli married his sister Maššanauzzi to its king, Mašturi. See The Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša, and the Šaušgamuwa of Amurru Treaty (CTH #105). Kaškans managed to get to Kahha, in the south, where Muwatalli's brother, Hattušili, stopped them. Muwatalli strengthened the borders against the Kaškaeans. Tarhuntašša: Muwatalli moved his capital to Tarhuntašša, and placed Hattuša in Hattušili's domain (It was sacked.). Hattuša was place under the direction of Mittannamuwa (Hoffner (1992) 46). Mittannamuwa was the Chief Scribe (Unal (1989) Festschrift T. Ozgüç, p. 506.). The move took place before the Battle of Kadesh (1275) (See Hoffner (1992) 47). Wiluša: Alakšandu the vassal king in Wiluša. See The Treaty with Alakšandu of Wiluša. The Loss of Southern Syria: Early in Muwatalli's reign, Seti I (1318-1304) campaigned in Syria and captured Amurru and then Kinza. The king of Amurru, Benti-šina, sent a formal declaration of the forced switch of loyalty. Seti couldn't maintain Syria, however. Seti may have made treaty with Muwatalli establishing the border somewhere to the south of Qadeš (If he did, then Muršili II did not make a treaty with Egypt.) This is the first reign in which the land of Lukka, which is better known in history as “Lycia” on the southwest corner of Anatolia, enters our story. The people of Lukka appear as a Hittite ally at the Battle of Kadesh and as a territory from which Muwattalli could go on campaign in the Alakšandu treaty. But their history is actually quite long. The earliest possible appearance of the Lukka occcurs ca. 2000 B.C., long before even the Hittite Old Kingdom. At that time they appear in an Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription on an obelisk in the “Temple of Obelisks” at Gubla (Byblos). The obelisk is in honor of “Kwkwn, son of Rwqq”. Albright (BASOR 155 (1959) 33f.) claims that Kwkwn could be an Egyptized form of Kukunni (Kwkwni?), which was the name of the predecessor of Alakšandu, and that Rwqq could be an Egyptized form of Lukk(a). The next mention of the Lukka occurs in the Amarna letters, where a king of Alašiya writes to Ahen-Aton and refers to a raid on Egypt by the Lukka. Raids on Alašiya by west Anatolian peoples seems to have been quite common. The next reference to them is the Battle of Kadesh reliefs. |

|

| Some or all info taken from Hittites.info Free JavaScripts provided by The JavaScript Source | |